The Digital Asset Market Structure (“DAMS”) discussion draft bill attempts to provide regulatory clarity on crucial blockchain industry issues. These issues include when a blockchain is legally considered decentralized, the relationships between the differing administrative agencies responsible for overseeing the industry, and a realistic path for legally compliant blockchain development and token sales in the US. But where will this regulation get in the way of development, and what areas of industry concern are missing from DAMS?

Here is background on how this bill came to be, what aspects of DAMS are most important/most likely to be heavily debated, and what can be expected going forward.

Background on DAMS

On June 2, 2023, Patrick McHenry, Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, and Glenn “GT” Thompson, Chairman of the House Committee on Agriculture, released a discussion draft of a proposed legislation, intending to provide the first statutory framework for digital asset regulations in the United States. The goal of the legislation is to “provide clarity, fill regulatory gaps, and foster innovation while providing adequate consumer protections.” Such legislation comes at a time when the US has not adopted any nationwide digital asset regulation, while at least 30 countries have done so.

The DAMS bill is a culmination of the work between the House Financial Services Committee, which is responsible for overseeing the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and other financial regulatory agencies, and the House Committee on Agriculture, which is responsible for overseeing the Commodities Futures Exchange Committee (“CFTC”).

A comprehensive digital asset legislation proposal has been expected for months. In April, Representative McHenry made multiple appearances, including at the blockchain industry conference Consensus, where he promised that the House would have a crypto legislation passed in the next few months. In May, the House held a joint Financial Services/Agriculture Subcommittee hearing entitled “The Future of Digital Assets: Measuring the Regulatory Gaps in the Digital Asset Markets.”

The discussion draft bill is 162 pages and is available here. A section-by-section summary can be found here, along with a two-page summary. Since this is only a discussion draft, many changes and iterations can be expected between the current version and the final executable version. However, the amount of work that went into this discussion draft is typically reserved for legislation the drafters hope will be signed into law. The theory that this draft is intended to become passible legislation is further supported by the draft’s constructive and nuanced approach to digital assets.

Most Important Features of DAMS

One of the major issues preventing further development of the over $1 trillion blockchain industry in the US is the lack of clarity on whether a digital asset is a security, a commodity, or a currency. If a digital asset is a security, it needs to be registered with the SEC or otherwise meet certain exemptions to registration. In comparison, if it is a commodity, it will be regulated by different administrative agencies like the CFTC and the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”).

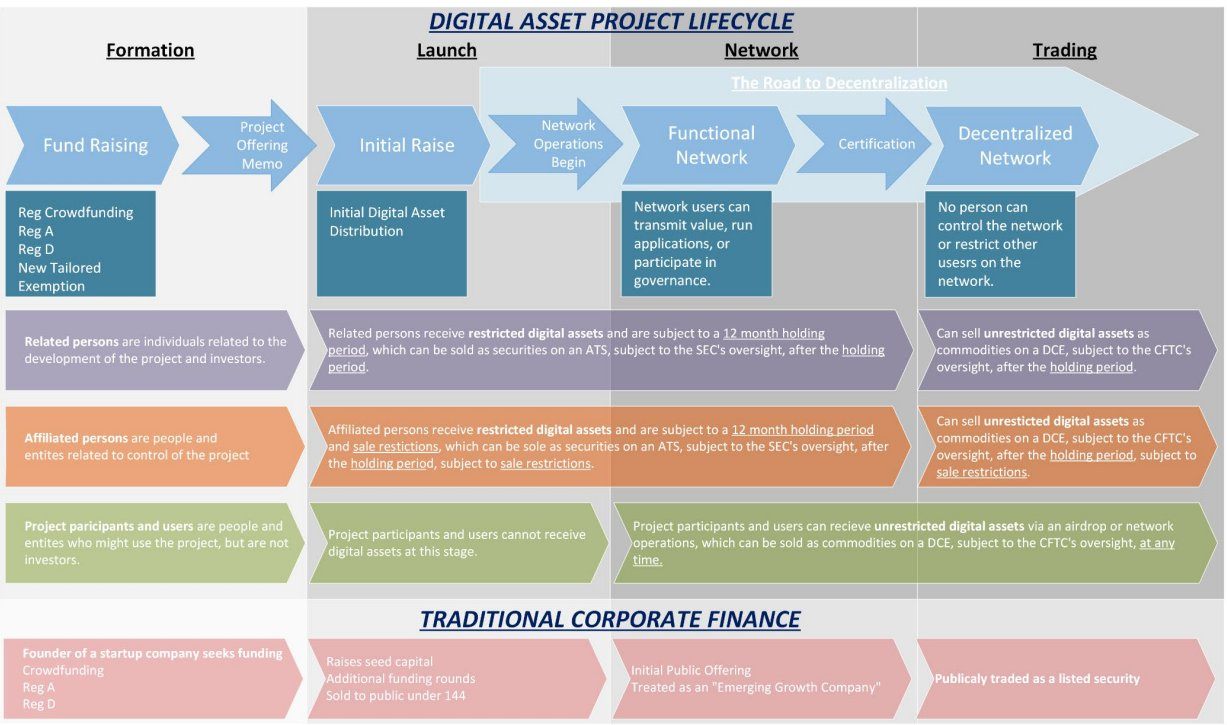

This proposed legislation seeks to provide clarity in two ways. The first is to create an SEC exemption specifically tailored to the initial sale of digital assets in the same way that the crowdfunding framework was specifically tailored for smaller businesses as a result of the JOBS Act. The DAMS summary included a flowchart (see below) that shows what the drafters envision this exemption to look like, and how it compares to more traditional capital-raising efforts such as through Initial Public Offerings (“IPOs”).

This exemption provides a road map for blockchain developers to build their blockchain projects and raise funds using Initial Coin Offerings (“ICOs”) while still providing investor protections in the form of disclosures and transferability restrictions. It also allows developers to eventually fall outside of the disclosure regime when the blockchain underlying the digital asset becomes “decentralized” and the original issuers are no longer the key drivers of the continued building or growth of the network.

One way to provide investor protection is by making the sale of tokens by “insiders” (i.e., the token issuers or developers and their close affiliates) regulated by a set of rules modeled after the traditional structures for private company equity securities with lock-up periods and limited exchanges to which those tokens can be sold.

DAMS also seeks to clarify when a blockchain network is “decentralized.” In other words, at which point the blockchain’s native tokens would be presumed to be commodities and fall outside of various disclosure and reporting regimes. DAMS defines a “Decentralized Network” as one where:

(1) no single entity (excluding DAOs) has had unilateral control over for the past year;

(2) the issuer/affiliates have not owned or had voting power of more than 20% of tokens for the past year;

(3) has not had its code substantially changed by issuer or affiliates in the past 3 months;

(4) has not been marketed by issuer or affiliates in the past 3 months; and

(5) all tokens issued in the past year were done programmatically (i.e., through mining/consensus rewards).

The draft provides guidelines on the regulations applicable to a blockchain network once it is deemed a “Decentralized Network” as defined in DAMS. Without these DAMS-provided guidelines (as developers are currently working under), blockchain networks considering whether to register their tokens as securities with intent to eventually decentralize that network run into a Catch-22. Since once the network is decentralized, there is no central actor with the practical ability to comply with the SEC’s ongoing reporting rules while the SEC has no rules regarding a token issuing company’s compliance requirements when its blockchain network is decentralized. This is the problem Blockstack ran into back in 2020, when its claim to no longer have reporting obligations due to the decentralized nature of its blockchain network was neither approved nor denied by the agency.

Other Significant DAMS Features

While the biggest issues revolve around the securities versus commodities structuring and related definitions, there are also other important features of DAMS.

Firstly, digital assets are defined as being “fungible,” assumedly making it clear that non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) are not intended to be covered under this regulatory framework. It also defines a decentralized organization to exclude any organization that is “directly engaged in an activity that requires registration” with the SEC or CFTC.

Secondly, DAMS makes it clear that software that simply creates a digital asset does not qualify as an issuer. This seemingly indicates that the DAMS drafters are aware of the distinction between a fund-raising effort in the form of digital assets and the digital assets or code itself. It also provides a safe harbor for issuance in the form of airdrops and network participation rewards through its definition of the “end user distribution” and an explicit carve out of the end user distributions from securities laws.

Areas of Concern

A vast majority of industry participants would generally agree that some form of a workable industry framework is necessary for this industry to continue growing in the US. That said, even well-intentioned and reasonable regulatory guidelines can create potentially negative externalities as industry participants seek to meet those guidelines rather than do what is in the best interest of the blockchain network in question. Some fear this bill is trying to do too much too fast by including SEC exemptions for public sales instead of focusing solely on the core decentralization and technology issues.

For example, while it makes sense to limit the “decentralized network” to one that the issuer has not substantially changed in the prior three months as evidence of actual decentralization and functionality, it might also prevent an issuer from applying changes to their networks to address flaws for fear of regulatory noncompliance.

Additionally, while ensuring issuers do not own or control 20% or more of the network’s outstanding tokens appears to be a protection against centralized control, it also promotes the quickening of complete token issuance, which may not be in the best interest of every blockchain network depending on the networks’ goals and functionalities. Similarly, it will be hard to comply with some of the requirements, including the crowdfunding exemptions, without some level of anonymity forfeiture. It is also unclear how the lockup requirements will work in a system which often requires giving up control over tokens to participate meaningfully in many blockchains (through delegation of voting rights, staking to participate in the consensus mechanism, or other token functions).

Furthermore, DAMS does not attempt to create an entire new regulatory regime, as was done in the European approach in MiCA. Instead, it tries to find a home for digital assets in the existing US legal frameworks. The DAMS approach of not setting up a new class of digital asset regulation is likely the only practical one in at least the near term, given the political reality that this is still a relatively small industry as well as the general difficulty to pass broad legislation in the United States. However, this approach has its limitations as the Securities Acts are from the 1930s and the seminal cases defining classes of securities are from the 1940-50s. As such, using existing securities and commodities regimes to regulate digital assets will inevitably run into square-peg-round-hole problems trying to fit digital asset rules into World War II-era laws.

Another general critique of DAMS is that it is focused on the issue of fund-raising by doing an ICO, which today is no longer as important an issue as it was a few years ago. Today, most new projects raise funds through selling rights to future tokens to accredited investors or selling them to non-US persons under an exemption from registration. If DAMS would instead focus on secondary sales and decentralization, it might have a greater chance of passing and thus be more useful.

Conclusion

While DAMS appears to be a well-intentioned and thoroughly reasoned approach to a functional digital asset framework in the US, it is still in its very early stages in the legislative process, and it is possible that it will not get passed as a law. In particular, the partisan nature of the bill is problematic. McHenry noted that this “discussion draft is the first step toward delivering on Republicans’ commitment to develop clear rules of the road for the digital asset ecosystem.” Given the current political environment of a divided government, its success will depend on bi-partisan support for the bill, something that it does not publicly have yet.

Although statements that the proposed legislation being a Republication proposal could lead one to conclude that it was drafted without serious plan of getting it passed, the length and level of thought that went into the discussion draft bill lend weight to the claim by Representatives McHenry and others that they intend to pass comprehensive digital asset policy in at least the House.

Whether it is DAMS this year or some other bill in 2024, it seems that the legislative clarity the industry has been clamoring for remains a real possibility. It is yet to be seen whether that legislative clarity will be a boon for the industry or create a “be careful what you ask for” moment that may further drive the industry overseas.

As a final thought, although this legislation is not perfect, it is likely to provide at least some level of regular assistance to a number of blockchain and digital asset projects, such that it is worthwhile for the industry to engage with it if not to support it.

Majer Ma, Polsinelli Summer Associate, contributed to this report.

/>i

/>i