As of now, 12 states (CA, CO, CT, DE, IA, IN, MT, OR, TN, TX, UT, and VA) have passed comprehensive privacy laws that are in effect (CA, CT, CO, and VA), or are about to go into effect sometime soon (DE, IA, IN, MT, OR, TN, TX, and UT). If any of these laws apply to your business, it is important to note that each impose special requirements when it comes to processing what they respectively treat as sensitive personal information (also referred to as “sensitive data,” a type of “personal data” under some laws). These 12 states have adopted three different approaches to processing sensitive personal information (SPI).

What is sensitive personal information?

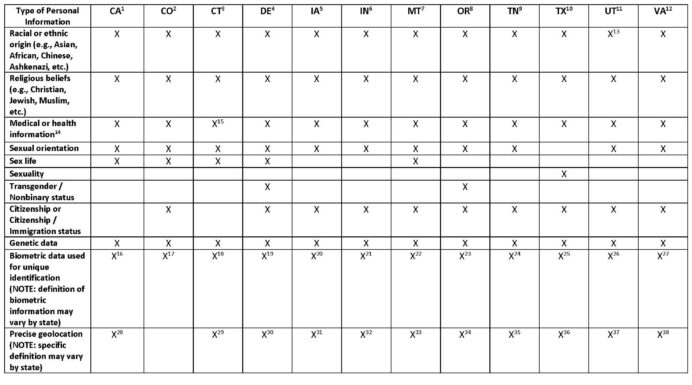

The answer depends on which state privacy laws apply. As the table below illustrates, while certain types of personal information are considered sensitive in all states, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), as amended, has a broader definition of SPI than the other states. In addition to the data types noted in the chart below, the CCPA’s definition of SPI also includes the following: account log-in, financial account, debit card, or credit card number in combination with any required security or access code, password, or credentials allowing access to an account, contents of a consumer’s communications where the business is not the recipient, government ID information (e.g., social security, driver’s license, state ID, or passport number), philosophical beliefs, and union membership.

1. California Residents Have the Right to Limit the Use of SPI

Under the CCPA, as amended, a business can process SPI without first obtaining the consent of a California resident (“CA Consumer”) so long as the business has the appropriate disclosures in its privacy policy. CA Consumers, however, have a right to limit the use of their SPI if it is being used to infer characteristics about them, or is being used for any other purpose outside those listed in Section 7027(m) of the updated CCPA regulations.

The Section 7027(m) permitted purposes, for which there is no right to limit, include when a business is processing SPI:

to provide goods/services reasonably expected by a requesting consumer (e.g., processing location to provide navigation features), or

and the processing is not done to infer characteristics about a consumer (e.g., providing a search engine of medical conditions).

If the business’s use of a CA Consumer’s SPI falls outside of the Section 7027(m) permitted purposes, CA Consumers have a right to limit the use of their SPI. A business must advise CA Consumers of their right to limit, and offer at least two methods, to submit a request to limit, one of which must reflect the manner in which the business primarily interacts with the individual. If a business collects SPI online, it must post either a “Limit the Use of My Sensitive Personal Information” link or a valid alternative opt-out link in the website footer.

A business that receives a request to limit must, as soon as feasible, but no later than 15 business days after receiving the request, take the following steps:

Stop all use and disclosure of SPI for any unpermitted purposes (those not listed in 7027(m));

Notify all service providers that process SPI for unpermitted purposes on your behalf to comply with the request to limit; and

Notify all third parties to whom you disclosed the SPI for unpermitted purposes of the request and direct them to: (a) comply with the request; and (b) forward the request to any other person with whom the third party has disclosed the SPI.

If a CA Consumer has limited the use of their SPI, a business cannot ask them to consent to the use for unpermitted purposes for at least 12 months after receiving their request to limit.

2. Nine States Require Data Protection Assessments and Opt-in Consent Before Processing SPI

Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Montana, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia each require a controller to perform a data protection assessment AND obtain valid opt-in consent of the individual (or, in the case of a child, their parent or guardian) that is a resident of those states BEFORE processing SPI.

Each of these laws adopt a similar definition of consent, meaning a clear affirmative act signifying an individual’s freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous agreement.

The Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Texas, and Montana definitions make clear that following actions do not constitute valid consent:

Acceptance of general or broad terms containing descriptions of data processing and other unrelated terms

Hovering over, muting, pausing, or closing a piece of content

Agreement obtained through dark patterns (an interface that impairs user autonomy, decision-making, or choice)

Similarly, the Oregon definition notes that the following actions do not constitute valid consent:

Agreement obtained through use of a mechanism that has the purpose or substantial effect of obtaining consent by obscuring, subverting, or impairing the consumer’s autonomy, decision-making or choice (i.e., agreement obtained through dark patterns); or

An individual’s inaction.

The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA) Rules provide additional clarity on what constitutes valid consent. Parsing the definition, Rule 7.03 appears to see valid consent as requiring the following five characteristics:

Clear affirmative action, meaning clear conduct or statements indicating acceptance.

Freely given, meaning it can be refused or revoked at any time without penalty.

Specific, meaning consent for unrelated purposes must be separately given.

Informed, meaning the individual was provided a clear notice containing certain information regarding the requested consent.

Unambiguous agreement, meaning it was not obtained through the use a dark pattern

Furthermore, if a consumer withdraws their consent, Colorado requires the controller to either delete SPI or render it permanently anonymized or inaccessible in a reasonable amount after such a withdrawal.

Colorado also has special rules regarding the processing of “sensitive data inferences,” which are inferences made by the controller from personal data that are used to indicate race, ethnic origin, religious beliefs, mental or physical health condition or diagnosis, sex life or sexual orientation, or citizenship or citizenship status.

In addition, in Texas, if a business is selling sensitive data, it must post the following notice in the same manner and location as its privacy policy (e.g., the website footer): “NOTICE: We may sell your sensitive personal data.” Similarly, if a business is selling biometric data, it must post the following in the same manner and location as its privacy policy: “NOTICE: We may sell your biometric personal data.”

Lastly, Connecticut has additional restrictions for processing “consumer health data,” a type of sensitive data. Specifically, businesses cannot (i) sell such data without obtaining consent; and (ii) use a 1,750-foot radius geofence around mental health, reproductive, or sexual health facilities to identify, track, collect, or send notifications related to consumer health data.

3. Two States Require the Consumer Be Provided a Clear Notice and the Right to Opt Out

In Iowa and Utah, a controller CANNOT process an Iowa or Utah resident’s SPI without first presenting them with a clear notice and opportunity to opt out of such processing.

Neither Iowa nor Utah law describes what constitutes such a clear notice and opportunity to opt out. However, because both laws state that such notice must be presented to consumers, any notice of processing SPI must be actively shown to the individual. Since the laws distinguish the SPI notice from the general privacy policy, simply presenting the full privacy policy containing details regarding SPI processing and advising of a right to opt out of such processing may be insufficient; thus, a separate SPI notice may be required.

Lastly, remember, just because you’ve complied with comprehensive state privacy laws does not mean you’re in the clear to process SPI.

There are numerous other federal, state, and local laws that may apply to processing of specific types of SPI. For example, there are many laws concerning genetic data. Illinois, Washington, and Texas have laws concerning biometric data; New York City does, too. Washington and Nevada have laws concerning personal health data.

Thus, it is important to always confirm and understand the various requirements of laws applicable to the SPI being processed.

[1] Ca. Civil Code § 1798.140(ae).

[2] Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1303(24).

[3] Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-515(38).

[4] Del. Code tit. 6 § 12D-102(30).

[5] Iowa Code § 715D.1(26).

[6] Ind. Code § 24-15-2-28.

[7] MCDPA § 2(24).

[8] OCPA § 1(18)(a).

[9] Tenn. Code § 47-18-3201(26).

[10] Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.001(29).

[11] Utah Code § 13-61-101(32).

[12] Va. Code § 59.1-575.

[13] Utah Code § 13-61-101(b)(i); however, the law exempts processing by a video communication service.

[14] In CA, this is defined as information concerning a consumer’s health. In CO MT, and OR, this is defined as a mental or physical health condition or diagnosis. In DE, this is defined as a mental or physical health condition or diagnosis, including pregnancy. In IA, TN, TX, and VA, this is defined as a mental or physical health diagnosis. In IN, this is defined as a mental or physical health diagnosis made by a health care provider. In UT, this is defined as medical history, a mental or physical health condition, or medical treatment or diagnosis; however, it is subject to exceptions for processing by certain licensed health care professionals. Utah Code § 13-61-101(b)(ii).

[15] CT considers: (i) a mental or physical health condition or diagnosis; and (ii) “consumer health data” to be sensitive data. Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-515(38). Consumer health data is defined as “any personal data that a controller uses to identify a consumer’s physical or mental health condition or diagnosis,” including but not limited to: (i) gender-affirming health data; and (ii) reproductive or sexual health data. Id. § 42-515(9).

[16] See Ca. Civil Code § 1798.140(c).

[17] See 4 Colo. Code Regs. § 904-3-2.02.

[18] See Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-515(4).

[19] See Del. Code tit. 6 § 12D-102(3).

[20] See Iowa Code § 715D.1(4).

[21] See Ind. Code § 24-15-2-4.

[22] See MCDPA § (2)3.

[23] See OCPA § 1(3).

[24] See Tenn. Code § 47-18-3201(3).

[25] See Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.001(3).

[26] See Utah Code § 13-61-101(6).

[27] See Va. Code § 59.1-575.

[28] See Ca. Civil Code § 1798.140(w).

[29] See Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-515(27).

[30] See Del. Code tit. 6 § 12D-102(22).

[31] See Iowa Code § 715D.1(19).

[32] See Ind. Code § 24-15-2-20.

[33] See MCDPA § 2(16).

[34] See OCPA § 1(18)(a)(C), 1(18)(b).

[35] See Tenn. Code § 47-18-3201(18).

[36] See Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.001(21).

[37] See Utah Code § 13-61-101(33).

[38] See Va. Code § 59.1-575.

[39] There are specific requirements for processing personal information of those younger than 16 years old. See Cal. Code Regs. tit. 11, §§ 7070–7072.

[40] In Colorado, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1303(4).

[41] CT adopts the definition of child under the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) (15 U.S.C. § 6501 et seq) (currently, anyone less than 13 years old). Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-515(6).

[42] DE adopts the definition of child under COPPA (currently, anyone less than 13 years old). Del. Code tit. 6 § 12D-102(5).

[43] In Iowa, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. Iowa Code § 715D.1(5).

[44] In Indiana, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. Ind. Code § 24-15-2-6.

[45] In Montana, a child is anyone less than 13 years old.MCDPA § 2(4).

[46] In Oregon, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. OCPA § 1(5).

[47] In Tennessee, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. Tenn. Code § 47-18-3201(5).

[48] In Texas, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.001(5).

[49] In Utah, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. Utah Code § 13-61-101(8).

[50] In Virginia, a child is anyone less than 13 years old. Va. Code § 59.1-575.

[51] See Cal. Civil Code § 1798.121 (granting the right to limit); Cal. Code Regs. tit. 11, § 7027(a).

[52] See Cal. Code Regs. tit. 11, § 7027(b).

[53] Id. § 7027(b)(1); see also id. § 7015 (outlining the requirement for a valid alternative opt-out link).

[54] Id. § 7027(g).

[55] Id. § 7027(l).

[56] See Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1309(2)(c); Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-522(2)(a)(4); Del. Code tit. 6 § 12D-108(a)(4); Ind. Code § 24-15-6-1(b)(4); OCPA § 8(1)(b)(C); MCDPA § 9(1)(d); Tenn. Code § 47-18-3206(a)(4); Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.105(a)(4); Va. Code § 59.1-580(A)(4) (each requiring controllers to perform data protection assessments when processing sensitive data); see also 4 Colo. Code Regs. § 904-3-8 (providing additional requirements for conducting assessments under CO law).

[57] See Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1308(7); Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-520(a)(4); Del. Code tit. 6 § 12D-106(a)(4); Ind. Code § 24-15-4-1(5); OCPA § 5(2)(b); MCDPA § 7(2)(b); Tenn. Code § 47-18-3204(a)(6); Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.101(b)(4); Va. Code § 59.1-578(A)(5) (each requiring opt-in consent).

[58] See Colo. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1303(5); Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-515(7); Del. Code tit. 6 § 12D-102(7); Ind. Code § 24-15-2-7; MCDPA § 2(5); OCPA § 1(6); Tenn. Code § 47-18-3201(6); Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.001(6); Va. Code § 59.1-575 (each defining consent).

[59] 4 Colo. Code Regs. § 904-3.

[60] Id. § 904-3-7.03(B)

[61] Id. § 904-3-7.03(C)

[62] Id. § 904-3-7.03(D)

[63] Id. § 904-3-7.03(E)

[64] Id. § 904-3-7.03(F); see also, id. § 904-3-7.09 (providing rules regarding dark patterns).

[65] Id. § 904-3-6.07(B)(3).

[66] See 4 Colo. Code Regs. § 904-3-2.02 (defining sensitive data inferences). The opt-in consent requirement for consumers over the age of 13 does not apply to sensitive data inferences, if (i) the processing purpose of such data is obvious to a reasonable consumer based on the context of collection and use of the data and the relationship between the controller and consumer; (ii) such inferences are permanently deleted within 24 hours of collection or completion of the processing activity (whichever is first); (iii) the inferences are not transferred, sold, or shared with processors, third parties, or affiliates; and (iv) the personal data and inferences are not processed for any purpose other than the express purpose disclosed to the consumer. 4 Colo Regs. § 904-3-6.10(B).

[67] Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.102(b).

[68] Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 541.102(c).

[69] Conn. Gen Stat. § 42-NEW(a) (CTDPA as amended by CT S.B. 3 (2023)).

[70] Id. § 42-NEW(a)(1)(C)-(D).

[71] See Iowa Code § 715D.4(2); Utah Code § 13-61-302(3)(a).

[72] Iowa Code § 715D.4(2); Utah Code § 13-61-302(3)(a).

[73] Compare Iowa Code § 715D.4(2) and Utah Code § 13-61-302(3)(a) (each describing the SPI notice), with Iowa Code § 715D.4(5) and Utah Code § 13-61-302(1) (each describing the general privacy notice).

[74] See, e.g., Cal. Civil Code §§ 56.18 et seq.; Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 20-448.02; Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (Pub. L. 110-233) 122. Stat. 881.

[75] See 740 ILCS §§ 14/1 et seq.; Wash. Rev. Code §§ 18.375.010 et seq.; Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 503.001; NYC Admin. Code §§ 22-1201 – 1205.

[76] See Washington My Health, My Data Act, H.B. 1155 (2023).

[77] See Nevada S.B. 370 (2023).

/>i

/>i