County firefighters and law enforcement officers who opt out of employer- or union-provided health insurance coverage receive a monetary credit each pay period, minus an “opt-out fee” that goes toward the costs of maintaining the insurance plans. Although the final credit received in their pay is part of their regular rate of pay for purposes of calculating overtime compensation under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), the employer did not include in the regular rate of pay the amount withheld as an opt-out fee. The Ninth Circuit held this was proper as the opt-out fees were correctly excluded under a statutory exception for health plan contributions. Sanders v. County of Ventura, No. 22-55663, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 31641 (Nov. 30, 2023).

“When an employer, as here, decides to allow employees to retain some portion of an unused health insurance credit, it can permissibly structure the program to prop up the employee health plans without treating the full amount of the health credit as part of the FLSA regular rate of pay,” the appeals court wrote and affirmed a district court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the county employer in an FLSA overtime collective action.

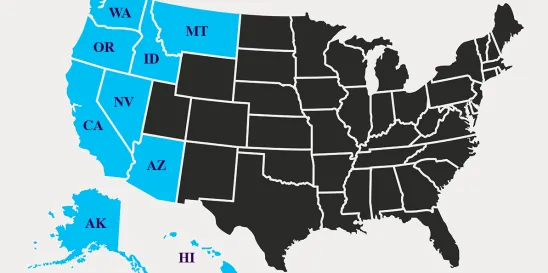

The Ninth Circuit has jurisdiction over federal courts in Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington state.

Opt-Out Fees

Ventura County firefighters and law enforcement officers receive a flexible benefit allowance every pay period, which they can use toward premiums for the county-sponsored health plan or union-sponsored plan. Those who opt out of coverage are also entitled to this monetary “flex credit” each pay period; however, a portion of this credit is deducted as a fee that the employer uses to fund the health plans.

The flex credit appears on employees’ pay stubs as “earnings,” and the opt-out fee appears as a “before tax deduction.” After the county subtracts the opt-out fee from the flex credit, it pays the balance to employees in cash. The opt-out fee (and, thus, the residual cash payment to employees who opt out) varies from year to year. The county treated the net cash payment to opt-out employees as part of their regular rate of pay when calculating their overtime compensation; however, the county did not include the value of the opt-out fee in the regular rate calculation.

A federal court in California held that the opt-out fee was excluded correctly under 29 U.S.C. § 207(e)(4), which excludes from the regular rate “contributions irrevocably made by an employer to a trustee or third person pursuant to a bona fide plan for providing health insurance.” The Ninth Circuit agreed.

Not a Cash-in-Lieu Payment

The plaintiffs cited Flores v. City of San Gabriel, 824 F.3d 890 (9th Cir. 2016) for the contention that the regular rate should include the opt-out fee. However, Flores distinguished between cash-in-lieu payments (which were to be included in the regular rate) and contributions to employees’ benefits (which may be included in the regular rate, depending on whether the program in question is a “bona fide plan” under Section 207(e)(4)). The plaintiffs argued that the opt-out fee is equivalent to a cash-in-lieu payment, but the appeals court said this reflects a misunderstanding of the nature of the opt-out fee. The opt-out fee does not function like the cash payment in Flores; instead, it is allocated to fund the health plans. The net cash payment does function like the cash payment in Flores, and the county treats it as such.

Paystub Description is Irrelevant

The plaintiffs pointed to the fact that the flex credits are displayed as “earnings” subject to a “before-tax deduction” (the opt-out fee). This was of no consequence, said the appeals court, because the paystubs reflect the requirements of the Internal Revenue Code, not the FLSA—and not the practical reality of the transactions. When determining the nature of the payment in question, what matters is what actually happens under the operative contract. Here, employees who opt out receive in cash only the amount left after the opt-out fee is subtracted.

Contributions Were “For Employees”

According to the plaintiffs, the exception outlined in § 207(e)(4) did not apply because they had opted out of the health insurance offerings — so the opt-out fee was not used to support their health care. The appeals court also rejected this argument, explaining that the statutory provision does not require that contributions be made for a particular employee’s benefits but “for employees” generally. And the opt-out fees, in this case, were used for employees who chose to participate in one of the available health plans.

No Deference Due on 20-Percent Cap

Finally, the plaintiffs asserted that the flexible benefits program was not a “bona fide” plan within the meaning of Sec 207(e)(4) because the flex credit exceeded 20 percent of the county’s total contributions for plan participants. In Flores, the appeals court had rejected a 20-percent ceiling requirement. In so doing, it declined to give deference to a U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) 2003 opinion letter supporting a 20-percent cap because the DOL had offered no rationale for adopting the ceiling.

In this case, the plaintiffs cited a (post-Flores) DOL 2019 Final Rule provision reaffirming the 20-percent cash contribution limit. The Ninth Circuit, however, found the Rule also was “undeserving of deference” as it was premised solely on the rejected 2003 opinion letter. Moreover, the decades-old opinion letter relied on the outdated, unduly narrow construction of FLSA exemptions that the U.S. Supreme Court expressly disapproved in its 2018 decision in Encino Motorcars, LLC v. Navarro.

At any rate, the appeals court found, the 20-percent cap applies to cash payments—not to the opt-out fees at issue here. The appeals court found that the net cash payments were under the 20% cap anyway.

/>i

/>i