We all have memories associated with iconic (car) designs. It could be our grandparents’ car, the car we used to drive when we were younger or that cool model we could not afford as students. Car designs often become icons and reflect socio-economic status and, for this reason, the automotive industry often offers remakes of classic models, such as the new Fiat 500, the new Mini and, of course, the new Porsche 911.

What happens to the design protection for iconic cars when they form part of a new released model? These are the issues that were tested by Porsche in two recent cases decided by the EU General Court (decisions T-209/18 and T-210/18). The key question from an IP perspective was whether a design incorporating a remake has the requisite novelty and individual character and, thus, should be deemed valid.

The cases

In 2014, Autec AG, a German company selling car toys, applied to invalidate community registered designs 000198387-0001 and 001230593-0001 filed on 2 July 2004 and 20 August 2010 respectively, by Porsche for the Porsche 911 (the “RCDs”).

The claim was based on lack of novelty and individual character according to Articles 4, 5 and 6 of the Community Design Regulation (EC) 6/2002. The claimant argued that the RCDs did not differ from the prior German design registrations M9705639-0001 and 49906704-0001 filed on 10 December 1997 and 10 November 1999 respectively, for previous Porsche 911 models.

The prior German designs and the RCDs filed by Porsche are set out below:

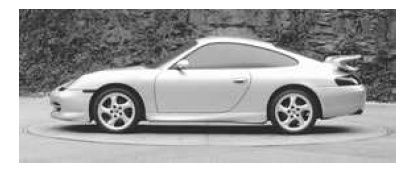

Prior German Design

Prior German Design

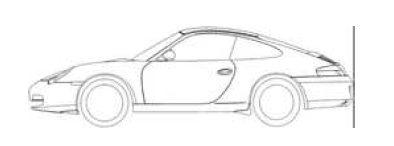

RCDs

Porsche argued that the Porsche 911 is such an iconic car that the informed user would pay a high level of attention to the details of the new model, and the freedom of the designer would be limited in light of consumers’ expectations. As a result, small differences would play an important role in creating a different overall impression and, thus, in differentiating the remake from the original model.

The cancellation division of the EUIPO, the Board of Appeal and, more recently, the EU General Court agreed that the essential characteristics of the RCDs, namely the shape of the car, the doors and the windows are identical in all the designs. Therefore, the overall impression of the RCDs is dominated by a structure similar to the prior German designs.

The EU General Court held that the informed user is a car passenger in general, not a Porsche 911 user. Similarly, the freedom of the designer may certainly be limited by technical constraints, such as the number of mirrors that a car should have, but no additional limitations derive from the fact that the Porsche 911 is an iconic design and consumers may have certain expectations regarding the shape or appearance of that car.

Conclusion and practical implications

On 6 June 2019, the EU General Court confirmed cancellation of the RCDs and, although the German designs will still be in force for a few years, the claimant may soon be able to reproduce the Porsche 911 without paying a licence fee to Porsche.

Although these decisions aim to prevent a registered design from obtaining protection for more than 25 years, they will have a considerable impact in the automotive industry and other industries where “nostalgic” products may be the focus of a design strategy and, potentially, the next popular model product.

The decision suggests that, in order to obtain protection for an updated version of a “classic” design in Europe, consideration must be given to maintaining the iconic appeal while changing the overall impression of more than just a few features that would be noticed by a highly specialised user. This will be a challenge for designers who wish to maintain the authenticity and “retro” look of older products. As an alternative, designers may consider registering parts of a new design in addition to the design as a whole, and considering their options to assert unregistered design rights in the first three years of disclosure, to attempt to prevent third parties from reproducing a (not so) new design.

/>i

/>i