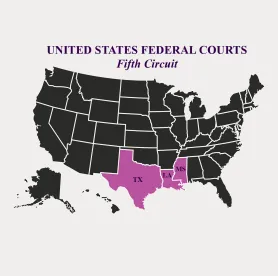

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in Hamilton v. Dallas County, held that plaintiffs no longer need to plead an “ultimate employment decision” before alleging a claim for disparate treatment under Title VII. Instead, a plaintiff need only allege discrimination because of a protected characteristic with respect to hiring, firing, compensation, or the ‘terms, conditions, or privileges of employment’ – a standard consistent with the other circuit courts of appeals that have ruled on this issue.

How We Got Here

In Hamilton, a group of female detention service officers alleged sex discrimination under Title VII on the basis that a scheduling policy allowed male officers to have both Saturdays and Sundays off while female officers received only weekdays or partial weekends off. A lower court dismissed the case, holding that an adverse employment action is needed for Title VII discrimination claims, which consists of "ultimate employment decisions" like hiring, granting leave, discharging, promoting, and compensating, and that changes to an employee’s work schedule, like denying weekends off, was not one.

The Fifth Circuit Abandons its Prior “Ultimate Employment Decision” Standard

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit reversed. It began by analyzing the text of Title VII and observed that “[n]owhere does Title VII say, explicitly or implicitly, that employment discrimination is lawful if limited to non-ultimate employment decisions.” The Court also noted that existing Supreme Court precedent supports that conclusion and cited to decisions stating that an adverse employment action “need only be a term, condition, or privilege of employment”; that a Title VII plaintiff may recover damages even for discrimination in the “terms, conditions, or privileges of employment” that did not involve a concrete effect on an employee’s employment status; and that Title VII’s coverage is not limited to “economic” or “tangible” discrimination. The Court went on to conclude that "[t]o adequately plead an adverse employment action, plaintiffs need not allege discrimination with respect to an ‘ultimate employment decision.’ Instead, a plaintiff need only show that [he or] she was discriminated against, because of a protected characteristic, with respect to hiring, firing, compensation, or the ‘terms, conditions, or privileges of employment’—just as [Title VII] says."

The Fifth Circuit declined to describe the “precise level of minimum workplace harm” that would suffice to meet this new standard, stating that it would leave such a question “for another day.” It made clear, however, that this new standard would not transform de minimis workplace trifles to an actionable Title VII claim and that “nearly every circuit court seems to have adopted one of these limitations” (like omitting de minimis workplace trifles) to liability for disparate treatment under Title VII.

Lessons for Employers

Hamilton now brings the Fifth Circuit in line with its sister circuits and the Supreme Court on this issue, and serves as a good reminder that when drafting or updating policies and procedures or taking most employment actions for that matter, make sure you are doing so for legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons. Employees should clearly understand the business-based rationale, even if they disagree with it, for the employment action, and more importantly, that it is not tied to their protected characteristics.

/>i

/>i