On 22 February 2024, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) published the statistics for federal civil fraud recoveries in Fiscal Year (FY) 2023.1 The DOJ announced that the “government and whistleblowers were party to 543 settlements and judgments, the highest number of settlements and judgments in a single year.”2 Despite the high number of settlements and judgments, FY 2023 saw the third lowest recovery amount in the last decade. As with prior years, the numbers highlight the general downward trend of False Claims Act (FCA) civil fraud recoveries.3 Remarkably, FY 2023 had the lowest percentage of health care-related new matters since 1995.4 Nevertheless, the US$1.8 billion in settlements and judgments involving the health care industry accounted for more than two-thirds of total recoveries.

In FY 2023, the DOJ highlighted five areas that they described as “key enforcement priorities.”5 These included health care fraud, procurement fraud, pandemic fraud, cybersecurity fraud, and individual accountability.6 Within those “key enforcement” areas, the government targeted health insurance companies,7 pharmacies,8 nursing facilities,9 and individual physicians,10 amongst other areas. The government also focused on COVID-19 and opioid epidemic-related fraud.11 As has been the case for at least the last decade and a half, the DOJ reinforced that fighting against fraud and abuse, “‘is of paramount importance to the Department of Justice.’”12 A summary of the DOJ’s report is further discussed below, as well as in a prior K&L Gates alert.

In this article, K&L Gates will discuss key developments from the first half of FY 2024, including notable settlements related to alleged kickbacks, medically unnecessary services, and controlled substances violations, among others. Additionally, K&L Gates will highlight three health care-related areas worthy of attention in FY 2024. First, after the US Supreme Court issued its decision in United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu in the summer of 2023, it remained uncertain how FCA litigation and interpretation of the FCA’s scienter standard would be affected by the case. This article discusses the observable impacts of that decision thus far. Second, the article discusses the circuit split on causation requirements in Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)-premised FCA actions. And, finally, with the almost endless and continual technological advancements impacting the health care industry, the article delves into the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in health care and fraud enforcement and the DOJ’s stance on its use.

FY 2023 Civil Fraud Recoveries

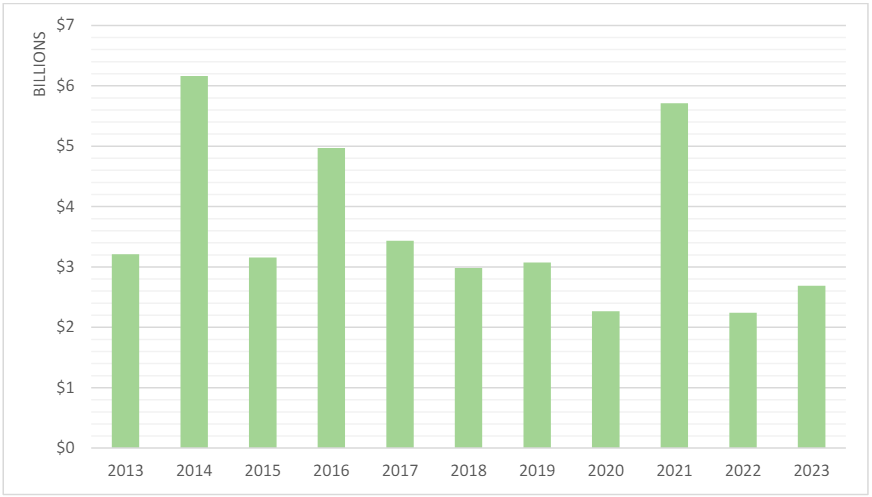

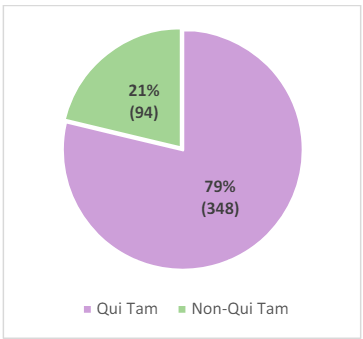

In FY 2023, the government’s FCA recoveries exceeded US$2.68 billion, surpassing the FY 2022 recoveries by nearly US$500 million.13 Additionally, FY 2023 marked the highest-ever number of FCA settlements and judgments in a single year, with 543 total settlements and judgments, as well as 1,212 total new matters. Despite the increase in recoveries and new matters,14 however, FY 2023 recoveries were the third lowest of the last decade.15

Figure 1: Total Civil Fraud Recoveries16

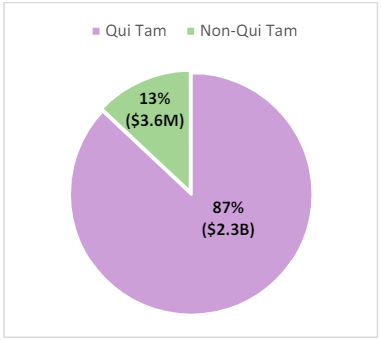

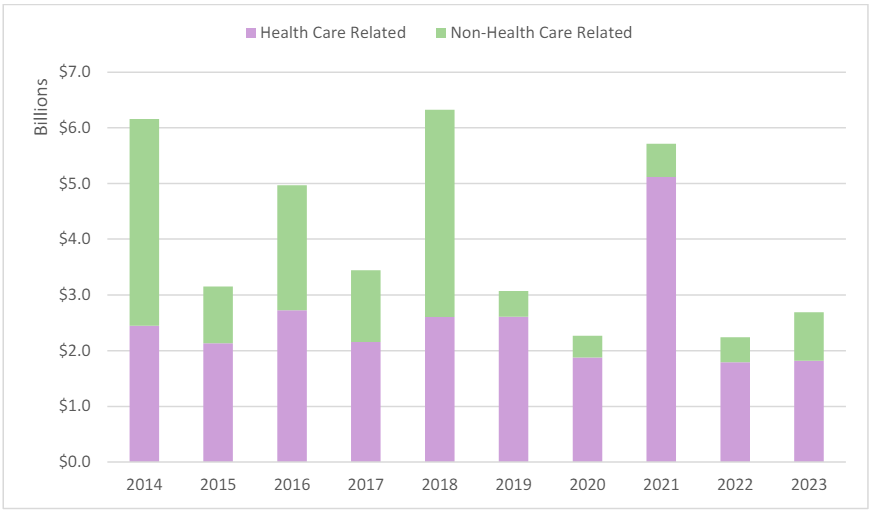

Focusing on FCA qui tam recoveries, FY 2023 saw an increase in qui tam-related settlements and judgments with just over US$2.3 billion in recoveries.17 As shown in Figure 2, this is the largest qui tam-related amount the government has recovered since before the pandemic, when it recovered US$2.2 billion in 2019.18

Figure 2: Total Qui Tam Recoveries19

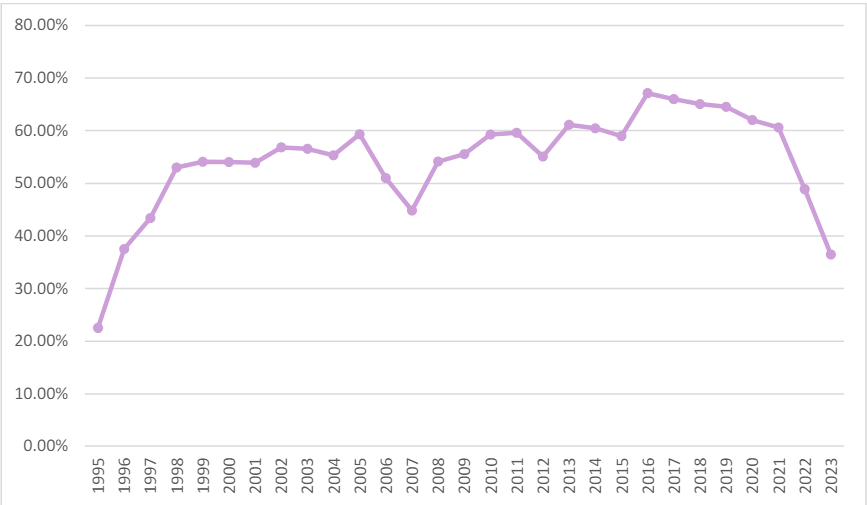

Further, with the exception of FY 2021,20qui tam actions have accounted for more than half of total FCA recoveries since 2006.21Qui tam matters continue to comprise the largest portion of the overall FCA recoveries (87% of matters in FY 2023).22

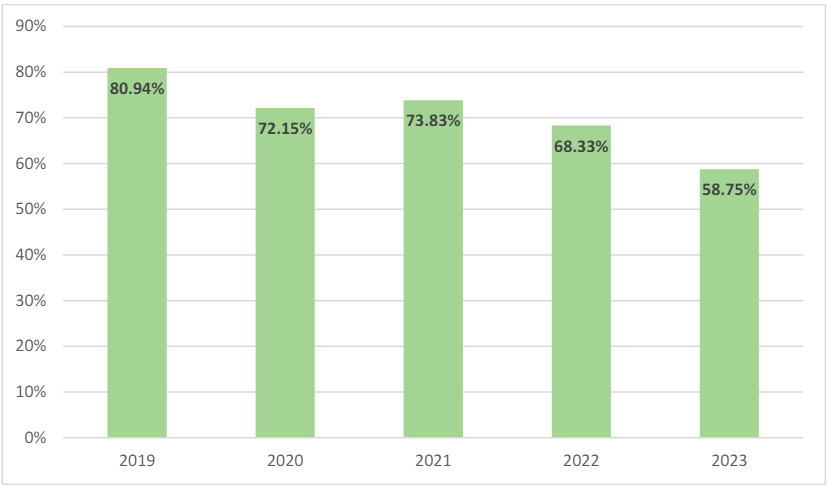

Figure 3: Qui Tam and Non-Qui Tam Recoveries for FY 202323

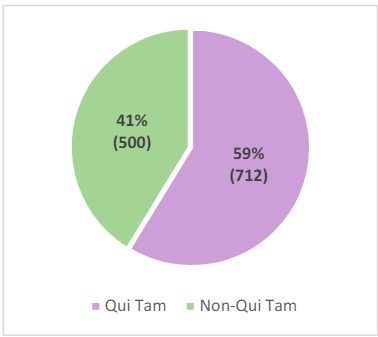

FY 2023 also saw an increase in the number of new qui tam matters. FY 2023 had 712 new qui tam matters, the largest since 2014.24 Despite the upward trends, the qui tam matter to non-qui tam matter ratio has actually decreased in the last five years.25 As shown in Figure 4, in FY 2019, qui tam matters accounted for 80.94% of all new FCA actions, while in FY 2023, qui tam matters made up only 58.75% of the new actions.26

Figure 4: Qui Tam-Related New FCA Matters as a Percentage of Overall New FCA Matters27

The general decrease in new qui tam matter percentages, however, should not distract from the fact that relators and the DOJ have continued to use qui tam actions as a weapon against fraud. Qui tam matters have accounted for at least 50% of all new FCA matters since 1994.28

As with prior years, health care-related FCA settlements and judgments have dominated other types of FCA recoveries. FY 2023’s health care-related recoveries increased by US$26 million from the prior fiscal year.31 The US$1.8 billion in health care-related recoveries made up over 67% of total recoveries for FY 2023. Notably, as illustrated in Figure 7, health carerelated recoveries have comprised the largest percentage of all FCA recoveries in each year since 2014, at which time they comprised only 39.73% of all recoveries.32

Surprisingly, however, at 36.47%, FY 2023 had the lowest percentage of new health carerelated matters filed since 1995, which is also the tenth lowest in the 37 years since the DOJ began tracking FCA statistics in FY 1987.34

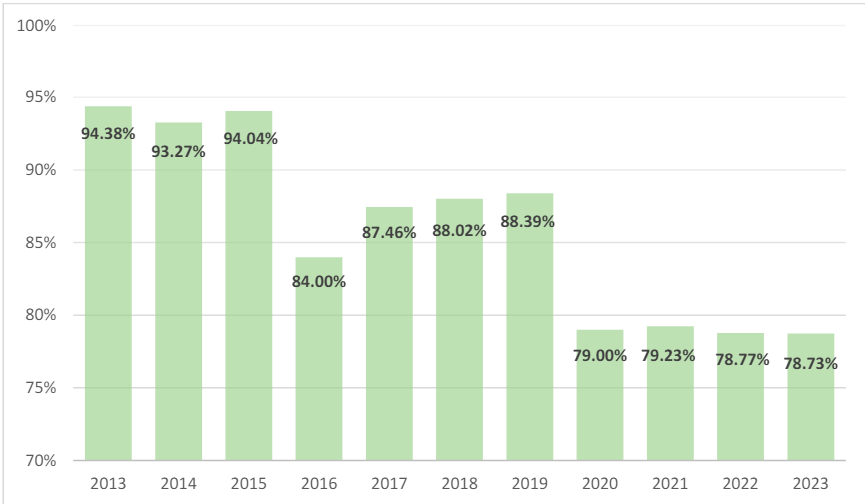

As with overall FCA qui tam actions, the percentage of health care-related FCA qui tam actions has also gradually decreased over the past decade. As shown in Figure 9, in FY 2013, health care-related qui tam actions accounted for 94.38% of all health care-related FCA matters, while in FY 2023, that number was down to 78.73%.36 Nevertheless, the majority of health care-related FCA actions continue to stem from whistleblower complaints.

Finally, FY 2023 was an anomaly in that, for the first time since 1997, non-health carerelated qui tam actions exceeded health care-related qui tam actions.38 Only 48.88% of FCA qui tam matters in FY 2023 were health care related.39

|

Health Care-Related Qui Tam Matters as a Percentage of Overall Qui Tam Matters |

|||

| Year | Percentage | Year | Percentage |

| 1997 | 49.09% | 2011 | 65.77% |

| 1998 | 58.97% | 2012 | 63.66% |

| 1999 | 63.89% | 2013 | 66.58% |

| 2000 | 58.40% | 2014 | 65.78% |

| 2001 | 57.64% | 2015 | 66.67% |

| 2002 | 60.82% | 2016 | 71.09% |

| 2003 | 64.37% | 2017 | 72.69% |

| 2004 | 63.19% | 2018 | 69.03% |

| 2005 | 66.34% | 2019 | 70.49% |

| 2006 | 56.10% | 2020 | 67.90% |

| 2007 | 54.52% | 2021 | 65.05% |

| 2008 | 60.95% | 2022 | 56.38% |

| 2009 | 64.43% | 2023 | 48.88% |

| 2010 | 66.84% | ||

Developments in the First Half of FY 2024

FY 2024 is already demonstrating the continuation of several enforcement priorities from FY 2023,41 with notable health care fraud settlements under the FCA, AKS, and Controlled Substances Act, among others.42 On 15 February 2024, the US Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York announced a settlement with a durable medical equipment (DME) company, which agreed to pay US$25.5 million to resolve FCA allegations that it paid kickbacks to beneficiaries and continued to bill government payors for the rental of noninvasive ventilators (NIVs) despite the beneficiaries lacking any support for continued need. Specifically, the government alleged that the DME company sought monthly reimbursement for devices despite purportedly knowing that beneficiaries were no longer using the devices.43 The DME company was also alleged to have granted coinsurance payment waivers for Medicare and TRICARE beneficiaries in order to persuade those beneficiaries to rent the company’s NIVs. This settlement is one of several in the first quarter of FY 2024 related to DME suppliers and laboratories upcoding and billing for medically unnecessary services or devices. 44

One example laboratory is Gamma Healthcare, Inc., a Missouri-based lab that, along with three of its owners, agreed to pay US$13.6 million to resolve allegations that it billed Medicare for medically unnecessary polymerase chain reaction (PCR) urinalysis laboratory tests.45 The DOJ announced the settlement, which included a 15-year exclusion from participating in federal health care programs, on 27 March 2024. In the press release, the DOJ stated that Gamma carried out the scheme by automatically performing and submitting claims for payment to Medicare for a urinary tract infection (UTI) panel of tests by PCR, which on average was reimbursed at a much higher rate—bringing the reimbursement amount from approximately US$11 to US$584. Notably, Gamma’s requisition forms were structured in a way that did not allow physicians to opt out of the UTI PCR tests and ignored requests to do so. According to the DOJ, physicians expressed concerns to Gamma about the UTI PCR Tests as early as March 2020, including expressly alerting Gamma that they did not order the tests and that the tests were expensive and not medically necessary.

There have also been several record-high recoveries, including a US$475.6 million settlement with an opioid manufacturer to resolve its civil liability under the FCA in connection with allegations related to losses to federal health care programs that paid for certain opioids.46

There were also a number of settlements related to Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, demonstrating that COVID-era fraud targeting efforts are far from over.47

Outlook for the Remainder of FY 2024

As highlighted above, the 543 settlements and judgments in FY 2023 marked the highestever number of settlements and judgments in a single year, with qui tam cases comprising the largest portion of recoveries (a trend that carried over from FY 2022).48 Despite these increases, FY 2023 saw the lowest number of health care-related FCA actions filed since FY 1995, continuing an apparent downward trend in overall health care-related FCA actions.49 While these trends are noteworthy, K&L Gates still expects government enforcement activity in the health care industry to be robust throughout the remainder of FY 2024. To that end, we believe that the following areas are worthy of monitoring in the second half of FY 2024:

- The impact of the Supreme Court’s decision in United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu, Inc.

- The growing circuit split regarding causation in kickback-premised FCA cases.

- The use of AI in health care and fraud enforcement.

This article discusses these areas in detail below, along with their potential impact on FCA liability and the overall enforcement environment in the remainder of FY 2024 and beyond.

The Impact of SuperValu

SuperValu and Polansky Decisions: A Brief Overview

FY 2023 was noteworthy, in part, given that the Supreme Court issued two separate FCA decisions in the same term: (1) United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu,50 and (2) United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources.51

On 1 June 2023, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in SuperValu, which was one of the most anticipated decisions in federal FCA jurisprudence in years. In a unanimous opinion drafted by Justice Clarence Thomas, the Supreme Court addressed what constitutes a “knowing” violation of the FCA. The Court held that the FCA’s scienter element “refers to the respondents’ knowledge and subjective beliefs—not to what an objectively reasonable person may have known or believed.”52

In Polansky, decided on 16 June 2023, the Supreme Court held that the federal government maintains the authority to dismiss a federal FCA action over a relator’s objection so long as the government first intervenes in the action.53 The Court also held that in assessing the government’s motion to dismiss a relator’s FCA action, district courts should apply the rule governing voluntary dismissal of suits in ordinary civil litigation.54 This decision—giving the government broad discretion to dismiss a qui tam action—may affect the government’s decision on when to intervene in an action. Additionally, the decision reinforces FCA defendants’ ability to urge the government for dismissal throughout the life cycle of the qui tam action, rather than solely at the pre-intervention phase.

Given the relatively narrow application of Polansky, the rest of this section is focused on SuperValu and the observable impacts of that decision thus far. However, for further discussion and analysis of the Polansky decision, please see the prior K&L Gates alert on that decision.

A Closer Look at the SuperValu Opinion

In its unanimous opinion in SuperValu, the Supreme Court held that “[w]hat matters for an FCA case is whether the defendant knew the claim was false. Thus, if respondents correctly interpreted the relevant phrase and believed their claims were false, then they could have known their claims were false.”55 The court made clear throughout its opinion that the decision was based squarely on the text of the FCA and the FCA’s roots in common-law fraud.56 Justice Thomas walked through the three mental states of scienter under the FCA— actual knowledge, deliberate ignorance, and reckless disregard—noting that this “three-part test largely tracks the traditional common-law scienter requirement for claims of fraud.”57 Before even addressing respondents’ arguments, the opinion made clear that “the FCA’s standards focus primarily on what respondents thought and believed.”58 Likewise, Justice Thomas maintained that “[b]oth the text and the common law also point to what the defendant thought when submitting the false claim—not what the defendant may have thought after submitting it.”59 In this manner, the Court addressed a major theme of the case—that the Seventh Circuit’s holdings in SuperValu and the parallel case, Safeway, would create “a safe harbor for fraudsters” where lawyers could conjure up “an innocent explanation” or post hoc justification that might render their claims accurate.60

The balance of the SuperValu opinion laid out respondents’ three main arguments and explained why the Supreme Court found none to be persuasive. First, respondents had argued that the “inherent ambiguity” of the terms “usual and customary” meant that the respondents could not have acted with the requisite scienter.61 While acknowledging the possible ambiguity, the Court held that “ambiguity does not preclude respondents from having learned [the terms’] correct meaning—or, at least, becoming aware of a substantial likelihood of the terms’ correct meaning.”62 The alleged facts in this case reflect that the respondents received notices that made them aware of the correct meaning of the phrase “usual and customary.” The Court noted that both respondents allegedly “received a notice in 2006 from a pharmacy benefit manager stating that the phrase ‘usual and customary’ refers to discounted prices” and that Safeway “apparently received the same message from state Medicaid agencies.”63 Additionally, in support of its holding, the Court laid out an illustrative analogy of a driver who sees a sign reading, “Drive Only Reasonable Speeds.” The Court reasoned that, while the term “reasonable” may be ambiguous, the driver could learn what constitutes an unreasonable speed from police or from the speed of surrounding vehicles.64 That analogy aside, the Court made clear that the “facial ambiguity” of a statute, regulation, or other relevant language “does not by itself preclude a finding of scienter under the FCA.”65

Second, the Supreme Court addressed Safeco Insurance Co. of America v. Burr, a Supreme Court case regarding the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which had been relied on by both the Seventh Circuit and respondents in briefing before the Supreme Court. Respondents had argued that, because the FCA and the FCRA contain the same commonlaw terms, Safeco’s interpretations of “knowing” and “reckless” should be applied in the FCA context.66 The Supreme Court distinguished Safeco given that it interpreted a different statute, FCRA, which had a different mens rea standard of “willfully.” The Court held that “[t]o take Safeco as establishing categorical rules for [knowingly and reckless] would accordingly ‘abandon the care we have traditionally taken to construe such words in their particular statutory context.’”67 Citing to a previous decision of the Supreme Court—which had declined to apply Safeco in the patent infringement context—the Court noted, “‘[n]othing in Safeco suggests that we should look to facts that the defendant neither knew nor had reason to know at the time he acted.’”68

Finally, respondents had argued that at common law, respondents’ claims would not be fraudulent given that they were mere misrepresentations of law rather than misrepresentations of fact.69 The Court noted that it “assume[d] without deciding that the FCA incorporates some version of this rule” that mere misrepresentations of law are not actionable.70 But, the Court maintained that, where a statement implies something about “facts that justify” a speaker’s statement, it may constitute a misrepresentation of fact.71 Here, the Court found that respondents had essentially said, “‘this is what our usual and customary prices are,’” which carried with it an implied statement of facts.72

The Impact of SuperValu Thus Far

The fallout from SuperValu will be seen in the years to come as district courts grapple with how to apply the Supreme Court’s decision. However, there are certainly insights to be gleaned from the cases that have addressed SuperValu in the months since the opinion was issued. The balance of this section will focus on the observable impacts of SuperValu to date, using representative cases as examples.

Remand of SuperValu-Like Cases

There were certain expected and immediate impacts from SuperValu. For example, the Supreme Court’s decision to remand United States ex rel. Sheldon v. Allergan Sales, LLC,73 and Ohlhausen v. Arriva Medical, LLC,74 to the Fourth and Eleventh Circuits, respectively, was anticipated. These cases involve very similar facts to those at play in SuperValu and, in light of the rejection of the “objectively reasonable interpretation” defense in SuperValu, the Supreme Court’s remand decision was logical. These cases remained pending at the time of this publication, and it will be important to keep an eye on the courts’ application of SuperValu in those cases as they provide valuable insights into how courts view SuperValu.

Declination to Dismiss on Scienter Grounds

In the immediate wake of SuperValu, it was predicted that defendants would no longer have as strong of an opportunity for a knockout blow in the early stages of a case—particularly at the motion-to-dismiss stage—on scienter-related grounds. Decisions to date have largely confirmed this prediction. For example, in United States v. Chattanooga-Hamilton County Hospital Authority, a district court found that the government had successfully pled an FCA claim against a defendant hospital operator for violating a Medicare regulation allowing reimbursement for “teaching-physician services” only “if the teaching physician personally provided the services, or if a resident provided the services while the teaching physician was present.”75 The defendant allegedly submitted reimbursement claims for teaching-physician services involving overlapping, resident-performed surgeries that were assigned to one teaching physician. The action implied that a single teaching physician could not be physically present at multiple, simultaneously occurring resident-performed surgeries.76 Relying on SuperValu, the district court found that allegations regarding the defendant’s status as “a sophisticated player in the healthcare industry,” compliance presentations and compliance meetings warning against overlapping surgeries, and other internal communications warning against reporting overlapping surgeries were sufficient to plead scienter.77 Of note, in denying the defendant’s motion to dismiss, the district court did not consider whether the defendant’s actions were consistent with a reasonable interpretation of the relevant regulation.78

Declination to Grant Summary Judgment on Scienter Grounds

While courts post-SuperValu appear less willing to grant motions to dismiss on scienter grounds, courts have also been less willing to grant motions for summary judgment on purely scienter grounds. Two examples help illustrate this interesting trend.

In United States ex rel. Heath v. Wisconsin Bell, Inc., the Seventh Circuit was tasked with determining whether to affirm or reverse the district court’s pre-SuperValu grant of summary judgment in favor of the defendant.79 The relator in Heath first filed suit in 2008, alleging that the defendant had violated the FCA by submitting and causing others to submit allegedly false reimbursement requests to an agent of the federal government.80 In March 2022, the district court had granted the defendant’s motion for summary judgment, finding that the relator failed to show a genuine dispute as to either falsity or scienter.81 Regarding scienter, the district court’s decision had relied on the objectively reasonable interpretation defense.82 In August 2023, the case came before the Seventh Circuit. Applying SuperValu, the Seventh Circuit found that there was enough evidence to establish a genuine dispute as to reckless disregard.83 The court first reasoned that, despite knowing of the relevant regulation since its creation, the defendant admitted that for years it had no procedures in place to assess compliance or any other way of knowing whether it was in compliance.84 In addition, the court observed that, even after the defendant implemented controls, evidence showed that the defendant was still overcharging relevant entities, which created at least a jury-triable issue as to scienter.85

While the Heath decision is favorable to plaintiffs, a recent decision from the District of Kansas proved to be favorable to defendants. In United States ex rel. Edalati v. Sabharwal, the defendant was charged with knowingly presenting false or fraudulent claims by using improper place-of-service codes to seek higher reimbursement rates from Medicare.86 The district court was faced with what it termed the “inverse” of the facts in SuperValu.87 Specifically, in Edalati, the regulation at issue was relatively unambiguous and the defendant contended that he subjectively believed the claims at issue were proper.88 The plaintiffs in Edalati argued that “reckless disregard” under the FCA should be interpreted using only an objective standard; however, the district court stated that the Supreme Court rejected such an interpretation in SuperValu.89 While the district court made clear that, under the facts, a jury could find that the defendant had acted with scienter, the district court held that SuperValu required the issue be sent to the jury.90

Limitations on SuperValu’s Impact

While the above cases show the impact that SuperValu has had thus far on FCA jurisprudence, there have been several opinions indicating potential limitations to the applicability of SuperValu. For example, in United States ex rel. Kraemer v. United Dairies, LLP, the Eighth Circuit held that an underlying insurance policy was ambiguous and that the defendant’s interpretation of that ambiguous policy was “objectively reasonable.”91 The Eighth Circuit distinguished its case from SuperValu, noting that, unlike the defendants in SuperValu, there was no evidence that the defendants in Kraemer had a “culpable state of mind” when the alleged false claims were made.92 The Eighth Circuit’s distinction emphasizes the very limited question that had been presented to the Supreme Court in SuperValu: “If respondents’ claims were false and they actually thought they were false . . . then would they have ‘knowingly’ submitted a false claim within the FCA’s meaning?”93 Given that limited question presented, and the facts at issue in SuperValu, there is a possibility that courts follow in the footsteps of the Eighth Circuit and decline to apply SuperValu where a defendant has an objectively reasonable interpretation and no facts exist to show the defendant actually thought that reasonable interpretation was false.

In addition, the Western District of Michigan has stated that, regarding claims for retaliation under 31 U.S.C. § 3730, “SuperValu did not change the standard for protected activity . . . and the Court declines to interpret it as doing so.”94 Therefore, it appears that courts may limit the applicability of SuperValu to 31 U.S.C. § 3729 and decline to extend its impact to the elements of FCA retaliation claims.

Other Notable Developments in the Wake of SuperValu

While the true impacts of SuperValu will likely take years to fully develop, the uncertainties it has created are more apparent. In clarifying scienter, the court may have inadvertently created uncertainty as to the “deliberate ignorance” and “reckless disregard” standards for scienter under the FCA. This uncertainty has led to some creative lawyering, particularly as it relates to the meaning of “reckless disregard.”

In SuperValu, the Supreme Court stated that reckless disregard “captures defendants who are conscious of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that their claims are false, but submit the claims anyway.”95 The Supreme Court did not provide any further clarity as to what it considers to be a “substantial and unjustifiable risk,” and this issue is likely to spur a large amount of litigation in the years to come. More immediately, the Supreme Court’s definition of reckless disregard led some on the defense bar to argue that reckless disregard involves a three-part test:

The Supreme Court clarified that the FCA’s “reckless disregard” standard “captures defendants who are [1] conscious of a [2] substantial and [3] unjustifiable risk that their claims are false, but submit them anyway.” . . . The [relator’s complaint] fails under this three-part test, as it does not allege that [the defendant] consciously disregarded a substantial risk of noncompliance, let alone that it did so without justification.96

This three-part test argument received immediate attention from the DOJ, which was quick to file a statement of interest arguing:

[T]he [Supreme] Court certainly did not establish a new “three-part test” for reckless disregard.97 Instead, the Court simply stated the “straightforward” point that the FCA’s “scienter element refers to respondents’ knowledge and subjective beliefs—not to what an objectively reasonable person may have known or believed.”98

Of note, the district court did not seem convinced by the three-part test argument, finding that the relator had sufficiently alleged scienter to survive the defendants’ motion to dismiss on that ground.99

In addition, the DOJ has used dicta from SuperValu to support its arguments as to what constitutes sufficient causation in AKS-premised FCA actions.100 Specifically, the Sixth Circuit and Eighth Circuit decided that a more defendant-friendly “but-for” causation requirement applies, and they did so by borrowing a definition from a separate statutory context.101 This has led the DOJ to cite to SuperValu’s language stressing the importance of construing words in their particular statutory context.102 This topic and the broader circuit split over causation in kickback-premised FCA actions are discussed in the section immediately below.

The Growing Circuit Split Regarding Causation in Kickback-Premised FCA Cases

Introduction

With the Supreme Court now having issued its decision in SuperValu, the question naturally turns to the next “big ticket” issue in FCA jurisprudence, which may also find itself before the high court. One primary candidate is the issue of what is required to prove causation in FCA actions premised on kickback and referral schemes under the AKS. This issue has divided circuits, with the Third Circuit requiring merely some causal connection,103 and the Sixth and Eighth Circuits requiring “but-for” causation between the alleged kickback and the claim for payment.104 The First Circuit is set to join this growing split,105 having granted an interlocutory appeal on the issue following decisions from two judges in the District of Massachusetts that landed on opposite sides of the issue.106

This circuit split has major implications for health care providers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and other entities operating in the health care environment. Both the government and qui tam relators have brought FCA cases premised on alleged kickback schemes, and these FCA cases pose significant potential liability. For example, Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.—one of the defendants in the aforementioned Massachusetts cases—is facing potential liability upwards of US$10 billion from an FCA suit premised on an alleged kickback scheme.107 A higher, but-for standard for causation would be a key tool for FCA defendants to defend against such cases.

Background on AKS-Predicated FCA Actions

An FCA action requires a showing of: (1) a false statement or fraudulent course of conduct (i.e., falsity), (2) that is made with scienter, (3) that was material, (4) causing the government to pay out money or forfeit moneys due.108 FCA actions can be predicated on violations of a myriad of laws and regulations, including those in the health care space such as the AKS. To establish falsity in an AKS-predicated FCA action, a plaintiff has historically needed to show that the defendant: (1) “knowingly and willfully,” (2) offered or paid remuneration, (3) “to induce” the purchase or ordering of products or items for which payment may be made under a federal health care program.109

In 2010, Congress added the following language to the AKS at 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g): “a claim that includes items or services resulting from a violation of [the AKS] constitutes a false or fraudulent claim for purposes of [the FCA].”110 Most courts have agreed that the AKS, therefore, imposes an additional causation requirement on FCA claims premised on AKS violations.111 While courts generally agree that some causation must be shown, courts are divided both on how to define “resulting from” and the applicable standard for proving causation.

The Growing Circuit Split

In its 2018 decision—United States ex rel. Greenfield v. Medco Health Solutions, Inc.—the Third Circuit was faced with the question of “what ‘link’ is sufficient to connect an alleged kickback scheme to a subsequent claim for reimbursement: a direct causal link, no link at all, or something in between.112 The Third Circuit ruled out the “no link at all” approach, finding that a relator “may not prevail on summary judgment simply by demonstrating that [the defendant] submitted federal claims while allegedly paying kickbacks.”113 However, the court also rejected a direct, “but-for” causation standard. In rejecting a but-for standard, the Third Circuit did not perform any statutory interpretation for the phrase “resulting from.”114 Rather, the court looked to the legislative history and concluded that a but-for standard would be contrary to the intent of the AKS’s drafters and “would dilute the [FCA]’s requirements vis-àvis the [AKS], as direct causation would be a precondition to bringing a [FCA] case but not an [AKS] case.115 The Third Circuit ultimately concluded that a defendant must demonstrate “some connection between a kickback and a subsequent reimbursement claim” to prove causation.116

Four years after the Greenfield decision, the Eighth Circuit was faced with the same question of how to interpret “resulting from” under 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g).117 In United States ex rel. Cairns v. D.S. Medical LLC, the Eighth Circuit declined to follow the Third Circuit, and instead, it held that “when a plaintiff seeks to establish falsity or fraud through [42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g)], it must prove that a defendant would not have included particular ‘items or services’ but for the illegal kickbacks.”118 Unlike the Third Circuit, the Eighth Circuit in Cairns based its decision on statutory interpretation.119 The court noted that the Supreme Court had previously interpreted the “nearly identical phrase, ‘results from,’ in the Controlled Substances Act.”120 In that case—Burrage v. United States—the Supreme Court had interpreted “results from” to require but-for causation.121 The Eighth Circuit followed the Supreme Court’s lead and found that the government’s arguments could not overcome the plain language meaning of “resulting from.”122

In April 2023, the Sixth Circuit issued its decision in United States ex rel. Martin v. Hathaway, joining the split and siding with the Eighth Circuit in adopting a but-for causation standard.123 As with the Eighth Circuit, the Sixth Circuit decided based on statutory interpretation, stating “[t]he ordinary meaning of ‘resulting from’ is but-for causation,” and the legislative history does not “overcome the ordinary meaning of the text.”124 The Sixth Circuit similarly cited to Burrage for support of its statutory interpretation.125 The Sixth Circuit additionally reasoned that “reading causation too loosely” would mean that “[m]uch of the workaday practice of medicine might fall within an expansive interpretation of the [AKS]” and would fail to “protect doctors of good intent,” whereas but-for causation “still leaves plenty of room to target genuine corruption.”126 Notably, in October 2023, the Supreme Court denied certiorari in Martin, allowing the circuit split to continue growing.127

The First Circuit is Next to Join the Split

As mentioned above, two judges in the District of Massachusetts ruled on this causation issue in mid-2023, landing on opposite sides.128 In July 2023, Judge Nathaniel Gorton granted the government’s motion for partial summary judgment in United States v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., adopting the Third Circuit’s standard from Greenfield that just “some connection” between a kickback and subsequent reimbursement claim is all that is required for causation under 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g).129 Judge Gorton stated that he was following the First Circuit’s guidance on this issue from its 2019 decision, Guilfoile v. Shields.130 Of note, Guilfoile only addressed whether the plaintiff had adequately pled an FCA retaliation claim rather than an FCA violation; however, Judge Gorton found this to be a distinction without a difference.131

Just two months later, in United States v. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Judge Dennis Saylor was faced with the same question of what causation standard should apply. Judge Saylor found that Guilfoile (and, therefore, Greenfield) was not binding because the First Circuit in Guilfoile had expressly stated that the issue before that court “was ‘not the standard for proving an FCA violation based on the AKS, but rather the requirements for pleading an FCA retaliation claim.’”132 Judge Saylor then analyzed the decisions and supporting rationales in each of Greenfield, Cairns, and Martin.133 Ultimately, Judge Saylor was persuaded by the statutory interpretation analysis of Cairns and Martin and applied a but-for standard.134

Following Judge Gorton’s ruling in Teva, the defendant moved to certify for interlocutory appeal the issue of what causation standard applies under 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g).135 Judge Gorton granted this motion on 14 August 2023,136 staying trial and sending the issue to the First Circuit, which officially certified the appeal on 17 November 2023.137 In Regeneron, the government similarly moved to certify the issue for interlocutory appeal, with Judge Saylor granting the motion on 25 October 2023, and the First Circuit certifying the appeal on 11 December 2023.138 With these two certifications, the First Circuit is poised to join the circuit split—on one side or the other—in 2024.

The Impact of AKS Causation on FCA Damages

There is a very real possibility that the most significant impact of the issue of causation in AKS-premised FCA claims is not on liability, but rather on the measure of damages for FCA defendants. A recent opinion from the Seventh Circuit in Stop Illinois Health Care Fraud, LLC v. Sayeed illustrates this point.139 In Sayeed, the defendant had set up a system where it agreed to pay a health care consortium for “management services” and “administrative advice[.]”140 However, the consortium allegedly also gave defendant full access to its clients’ health data, which the defendant used to directly solicit patients to provide medical services.141 The district court had found the defendant liable under the AKS and FCA, concluding that all Medicare claims submitted by the defendant for services provided to the consortium’s client after the date of the purported data-mining agreement were necessarily false.142 The defendants appealed both the liability and damages findings to the Seventh Circuit.143

While its appeal concerning liability failed, the defendant’s narrower challenge to the amount of damages—premised on the “resulting from” language of 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g)—proved more successful.144 The Seventh Circuit recognized the ongoing circuit split over the term “resulting from,” but it noted that this case did not require the Seventh Circuit to resolve the split over whether but-for causality applies versus some lesser showing given the nature of the kickback allegations at issue.145 The Seventh Circuit determined that the key— regardless of applicable causation standard—was whether the referring entity (the consortium) officially assigned any patients at issue “through its standard rotational-referral process” as that would undercut causation.146 The court stated:

Our review of the district court’s explanation for its damages award leaves us uncertain regarding which, if any, of the patients included on the loss spreadsheet were rotationally referred to the defendants. The district court approached the damages question more broadly by concluding that all Medicare claims submitted by the defendants for services provided to [the referring entity’s] clients after . . . (the effective date of the data-mining agreement) were necessarily false—regardless of whether they resulted from rotational referrals . . . That broad suggestion—that every claim for payment following an anti-kickback violation is automatically false regardless of its origin—is inconsistent with § 1320a-7b(g)’s directive that a false claim must “result[ ] from” an unlawful kickback.147

Given this conclusion, the Seventh Circuit opted to remand the case to the district court to determine whether any services in the plaintiff’s loss spreadsheet were provided to patients that were lawfully referred to the defendants by the referring consortium.148 In short, although the Seventh Circuit declined to weigh in on the circuit split, its decision to remand shows the significant potential impact that a causation standard (and 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g) generally) can have on the measure of FCA damages.

Key Takeaways

The First Circuit appears to be the next battleground for the ongoing dispute over what standard applies for proving causation under 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g). The Supreme Court declined to grant certiorari on this issue in Martin this past year. However, the growing confusion and disagreement among district and circuit courts over this issue, coupled with the issue’s import in FCA jurisprudence, make it a strong contender to be the next FCA issue decided by the Supreme Court. In fact, the issue could be before the Supreme Court soon after the First Circuit joins the split. From a practical standpoint, until this split is resolved, FCA practitioners must pay close attention to choice of venue in AKS-predicated FCA actions.

As noted above, a higher, but-for standard for causation would be an important tool for FCA defendants. But-for causation would allow a defendant to argue that, even if it had acted with an intent to induce referrals, no actual referrals resulted from the conduct and, therefore, no liability exists. Alternatively, and perhaps even more significantly, but-for causation may allow a defendant to argue that FCA damages are lower than the full amount of referrals made where the government is unable to prove that all of the referrals “resulted from” the improper arrangement.149

While awaiting a decision from the First Circuit, practitioners should also be aware of open questions here, including whether the Supreme Court’s holding in SuperValu will have a marked impact on arguments for but-for causation. As noted above, the Sixth Circuit’s and Eighth Circuit’s decisions to apply but-for causation were rooted in statutory interpretation, and particularly in the Supreme Court’s prior interpretation of the phrase “results from” in the Controlled Substances Act.150 In SuperValu, however, the Supreme Court stated that words must be construed in their particular statutory context.151 Plaintiffs—including the government in Regeneron—have begun to cite to this portion of SuperValu as evidence that the Sixth Circuit’s and Eighth Circuit’s analyses were flawed and but-for causation is improper.152 The court in Regeneron was not convinced, but it remains to be seen whether the argument will gain momentum as this circuit split continues to grow.

The Use of AI in Health Care and Fraud Enforcement

Shortly before the issuance of the DOJ’s Annual Report concerning civil fraud recoveries in FY 2023, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco delivered a speech about the benefits and dangers of the use of AI and machine learning (ML).153 She described society as being at an “inflection point” with this technology. Her comments highlighted the benefits of AI, including the use of AI and other similar technologies by the DOJ as an “indispensable tool to help identify, disrupt, and deter criminals.”154 This was not the only instance in which the DOJ has touted the use of AI and other data analytics tools in identifying potential targets for criminal investigations, including health care fraud. In its 2023 Annual Report, the Fraud Section of the Criminal Division described the Data Analytics Team within the Health Care Unit. The report indicated that this team had used data analytics to create “223 proactive investigative referrals” for potential health care fraud.155 These cases included instances of fraud in connection with the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Provider Relief Fund, as well as fraud by laboratories billing for COVID-19 testing.156

These DOJ announcements are consistent with the terms of President Biden’s Executive Order issued on 30 October 2023, which ordered all federal agencies to evaluate and plan for the use of AI and other similar technologies in their work.157 For example, that Executive Order directed the US Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “advance responsible AI innovation by a wide range of healthcare technology developers that promotes the welfare of patients and workers in the healthcare sector” and to “explore ways to improve healthcare-data quality to support the responsible development of AI tools for clinical care, real-world-evidence programs, population health, public health, and related research.”158 At the same time, however, HHS was ordered to consider how these technologies can be used to “detect unjust denials” of health care or other federal benefits administered by HHS.159 Likewise, the US Attorney General was ordered to “identify areas where AI can enhance law enforcement efficiency and accuracy.”160

As Deputy Attorney General Monaco underscored in her speech, “[e]very new technology is a double-edged sword, but AI may be the sharpest blade yet.”161 As acknowledged by both the President and the DOJ, AI has a huge potential to improve health care quality, to make the provision of services more efficient, and to develop new drugs and treatments. It also has huge benefits in identifying potential fraud by health care providers and insurers. However, with these benefits come significant risks as well.

One of the risks that has been identified by HHS is the use of AI by Medicare Advantage plans to deny medically necessary treatment to patients. On 6 February 2024, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a memorandum discussing coverage criteria used by Medicare Advantage plans.162 The memorandum was in the form of “frequently asked questions” to give guidance to the administrators of these plans. Although CMS acknowledged that AI can be used as a tool in making coverage decisions, it normally should not be used as the final determination, without the use of human oversight and decision-making.163 There are various reasons that CMS pointed out in its memorandum supporting this proposition. First, there is the danger that the coverage determination would be based primarily on “a larger data set instead of the individual patient's medical history, the physician’s recommendations, or clinical notes.”164 Second, the use of AI implicitly includes criteria that are not public. CMS said, “predictive algorithms or software tools cannot apply other internal coverage criteria that have not been explicitly made public and adopted in compliance with the evidentiary standard in [42 C.F.R.] § 422.101(b)(6).”165 Finally, CMS is “concerned that algorithms and many new artificial intelligence technologies can exacerbate discrimination and bias.”166 As the use of AI increases, including by health care providers and insurers, it is likely that there will be additional problems that arise in the use of AI, and more challenges to its use. The development and use of AI is increasing exponentially, and the potential for abuse is hard to overstate.

As both the DOJ and private actors increasingly utilize AI as a powerful tool, an additional question arises: Can AI ever be used as evidence in a civil or criminal trial? An article in the Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property addresses that question directly.167 That article discusses the difficulties in determining both the validity and reliability of evidence developed by AI, and how those problems affect admissibility in court. One of the problems is the transparency of the AI process so that litigants can test and challenge the validity and reliability of the information. As that article points out:

The problem with the requirement of transparency is that many modern AI techniques are not explainable because they are naturally opaque. . . . Unlike code, which can be examined for bugs, it is often not apparent how a machine-learning model has been developed or works, especially when it employs deep learning or neural networks.168

Even in situations where the evidence being used is merely a statistical extrapolation, not using AI, the concept of transparency can be crucial to the reliability of an expert’s opinion and its use by the government. In two separate cases, recently decided in two different federal districts, courts have effectively refused to allow the government’s extrapolation evidence unless the government can produce all of the evidence used to perform the extrapolation and demonstrate that the methodology used is reliable.169 In both of those cases, the provider was challenging the use of a particular statistical methodology that excluded “zero paid claims” from the universe of claims that was used in calculating a Medicare overpayment. This methodology was routinely used by Medicare contractors for many years, and it was specifically approved by CMS. However, the courts in both of these cases indicated that the health care provider had a right to see all of the underlying information that would be necessary to challenge the validity of these overpayment calculations, including the claims that the Medicare contractor decided to exclude from the universe of claims. One of the courts said, “[w]ithout the ability to verify the contractor’s calculations, a provider does not have the information and data necessary to mount a due process challenge to the statistical validity of the sample, as is its right.”170 One could imagine situations where evidence compiled by AI is attempted to be introduced into evidence, and the same argument is made. It is likely that it would not only be impractical, but very likely impossible, for a litigant to turn over all of the data that the AI used to form its conclusion.

The ultimate takeaway is that both the benefits and dangers of AI should be considered by health care professionals and attorneys alike, and this issue will become increasingly pressing in FY 2024 and beyond. Health care providers should consider how such technologies can improve patient safety and care, and how health care can be provided more effectively and efficiently. It also seems likely that companies using such tools are also going to be held responsible for asking the right questions of the software engineers to determine whether there are implicit biases in the AI algorithms and whether such programs are being continuously monitored for both validity and reliability. Government attorneys will need to understand that, while AI and similar technologies can be extremely helpful in identifying potential targets for investigation, the government must ultimately prove its case the old-fashioned way—with admissible evidence. Lawyers in the private sector, likewise, need to explore ways in which AI can be a useful tool in their toolbox to assist their clients in pursuing their aims at lower costs. But lawyers must also be cognizant of the limitations of the technology and the potential dangers of overreliance on its use. Finally, lawyers defending FCA cases or even repayment determinations by the government should educate themselves sufficiently about the limitations of AI or other technologies in order to challenge their use by the government. Because this technology and the law surrounding it is changing at “light speed,” attorneys must be continuously educating themselves about the most recent developments in this area of the law. In short, as the use of AI in the health care industry significantly expands, it seems inevitable that FCA cases involving AI-related issues will do the same.

Conclusion

FY 2023 FCA recoveries reinforced the government’s staunch commitment to using the FCA as the primary tool in combatting perceived fraud in health care. As discussed in detail above, the government’s FY 2023 recoveries exceeded those for FY 2022 and marked the highest-ever number of FCA settlements and judgments in a single year. FY 2023 also saw significant increases in qui tam-related settlements and judgments, as well as in new qui tam matters filed. To date, 2024 FCA activity has demonstrated similar trends, including a number of FCA settlements for DME suppliers and laboratories, large-scale recoveries against opioid manufacturers, and PPP loan enforcement.

With courts’ ongoing interpretations of SuperValu, the continued circuit split in AKSpredicated FCA actions, and the imminent proliferation of AI, the remainder of FY 2024 will undoubtedly prove to be an active and impactful period for the FCA in health care. K&L Gates will continue to actively monitor and report on these developments.

1 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., False Claims Act Settlements and Judgments Exceed $2.6 Billion in Fiscal Year 2023 (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/false-claims-act-settlements-and-judgments-exceed-268-billionfiscal-year-2023.

2 Id.

3 U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Statistics Overview (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/opa/media/1339306/dl?inline.

4 Id.

5 See supra note 1.

6 Id.

7 See, e.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Cigna Group to Pay $172 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (Sept. 30, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/cigna-group-pay-172-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations.

8 See, e.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Two Jacksonville Compounding Pharmacies and Their Owner Agree to Pay at Least $7.4 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (June 15, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/twojacksonville-compounding-pharmacies-and-their-owner-agree-pay-least-74-million-resolve.

9 See, e.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Landlord and Former Operators of Upstate New York Nursing Home Pay $7,168,000 to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations of Worthless Services Provided to Residents (Feb. 27, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/landlord-and-former-operators-upstate-new-york-nursing-home-pay-7168000-resolve-falseclaims.

10 See, e.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Dermatologist Agrees To Pay $6.6 Million To Settle Allegations Of Fraudulent Billing Practices (July 13, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/usao-edtn/pr/dermatologist-agrees-pay-66-millionsettle-allegations-fraudulent-billing-practices.

11 See supra note 1.

12 Id.

13 See supra note 3

14 Id.

15 Id.

16 Id.

17 Id.

18 Id.

19 Id.

20 FY 2021 included the US$2.8 billion resolution with Purdue Pharma. See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Justice Department Announces Global Resolution of Criminal and Civil Investigations with Opioid Manufacturer Purdue Pharma and Civil Settlement with Members of the Sackler Family (Oct. 21, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justicedepartment-announces-global-resolution-criminal-and-civil-investigations-opioid.

21 See supra note 3.

22 Id.

23 Id.

24 Id.

25 Id.

26 Id.

27 Id.

28 Id.

29 Id.

30 Id.

31 Id.

32 Id.

33 Id.

34 Id.

35 Id.

36 Id.

37 Id.

38 Id.

39 Id.

40 Id.

41 In addition to the health care-focused developments that have occurred in the first half of FY 2024, there have been notable developments across the DOJ’s other key enforcement priorities, including cybersecurity (which itself has import to the health care industry). For example, in April 2024, the DOJ made its first decision to intervene in a cybersecuritybased FCA qui tam. The case is United States ex rel. Craig v. Ga. Tech Rsch. Corp., No. 22-cv-02698 (N.D. Ga.).

42 One other noteworthy (non-settlement) development from the first half of FY 2024 was a Minnesota district court’s decision to cut a US$487 million FCA jury verdict, which was premised on AKS violations, down to roughly US$216 million on Eighth Amendment Excessive Fines Clause grounds. See United States ex rel. Fesenmaier v. Cameron-Ehlen Grp., Inc., No. 13-cv-03003, 2024 WL 489708 (D. Minn. Feb. 8, 2024). It remains to be seen whether other courts will follow the District of Minnesota’s lead as it relates to large FCA jury verdicts.

43 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., U.S. Attorney Announces $25.5 Million Settlement With Durable Medical Equipment Supplier For Fraudulent Billing Practices (Feb. 15, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/us-attorney-announces255-million-settlement-durable-medical-equipment-supplier.

44 See, e.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Durable Medical Equipment Companies to Pay Millions in False Claims Settlement (Jan. 26, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sc/pr/durable-medical-equipment-companies-pay-millions-falseclaims-settlement (announcing settlement with several DME companies that provided medical beds and related pressure support surfaces to federal health care program beneficiaries and agreed to pay US$2.1 million to resolve allegations of false billing, including for used beds as if they were new; upcoding certain support products to increase reimbursement; and billing travel time as repair time to make it a reimbursable expense); Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Kentucky Lab Agrees to $4.9 Million Civil Judgment and Drug Treatment Center Enters Settlement to Pay $2.2 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (Jan. 30, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/usao-edky/pr/kentucky-lab-agrees-49-million-civil-judgment-and-drugtreatment-center-enters (announcing settlement with a Kentucky laboratory and treatment center that agreed to pay US$2.25 million and to enter a corporate integrity agreement, and separately entered into an agreed judgment in the amount of nearly US$5 million).

45 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Gamma Healthcare and Three of Its Owners Agree to Pay $13.6 Million for Allegedly Billing Medicare for Lab Tests That Were Not Ordered or Medically Necessary (Mar. 27, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/gamma-healthcare-and-three-its-owners-agree-pay-136-million-allegedly-billing-medicarelab.

46 Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Opioid Manufacturer Agrees to Global Resolution of Criminal and Civil Investigations into Sales and Marketing of Branded Opioid Drug (Feb. 29, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/opioid-manufacturerendo-health-solutions-inc-agrees-global-resolution-criminal-and-civil.

47 See, e.g., Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., Company that improperly took COVID 19 PPP loan agrees to pay nearly $1 million to settle False Claims Act case (Mar. 11, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/usao-wdwa/pr/company-improperlytook-covid-19-ppp-loan-agrees-pay-nearly-1-million-settle-false; Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Just., AmeriHealth Clinics Consent to a $2 Million Judgment to Resolve Healthcare Fraud Allegations (Jan. 17, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/usaoid/pr/amerihealth-clinics-consent-2-million-judgment-resolve-healthcare-fraud-allegations.

48 See supra note 3.

49 Id.

50 143 S. Ct. 1391 (2023). In SuperValu, the Supreme Court decided on the Seventh Circuit’s decision in SuperValu and its decision in United States ex rel. Proctor v. Safeway, Inc. See United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu, Inc., No. 21- 1326, 2023 WL 178398 (S. Ct. Jan. 13, 2023) (granting Petition for Writ of Certiorari); United States ex rel. Proctor v. Safeway, Inc., No. 22-111, 2023 WL 178393 (S. Ct. Jan. 13, 2023) (granting Petition for Writ of Certiorari).

51 143 S. Ct. 1720 (2023).

52 SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1399.

53 Polansky, 143 S. Ct. at 1727.

54 Id.

55 SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1396.

56 See id. at 1399–1404.

57 Id. at 1400.

58 Id.

59 Id. at 1401 (emphasis in original).

60 United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu, 9 F.4th 455, 476 (7th Cir. 2021) (Hamilton, J., dissenting).

61 SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1401.

62 Id. at 1402.

63 Id. at 1398.

64 Id. at 1402.

65 Id.

66 Id.

67 Id. (quoting Jerman v. Carlisle, McNellie, Rini, Kramer & Ulrich, L.P.A., 559 U.S. 573, 585 (2010)).

68 SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1403 (quoting Halo Elecs., Inc. v. Pulse Elecs., Inc., 579 U.S. 93, 106 (2016)).

69 SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1403.

70 Id.

71 Id. at 1403–04.

72 Id. at 1404

73 143 S. Ct. 2686 (2023) (“Judgment vacated, and case remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit for further consideration in light of United States ex rel. Schutte v. Supervalu Inc.”).

74 143 S. Ct. 2686 (2023) (“Judgment vacated, and case remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit for further consideration in light of United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu Inc.”).

75 21-cv-00084, 2024 WL 221758, at *1 (E.D. Tenn. Jan. 19, 2024).

76 Id. at *2.

77 Id. at *7–8.

78 See generally id.

79 92 F.4th 654, 662–64 (7th Cir. 2024).

80 Id. at 659.

81 United States ex rel. Heath v. Wisconsin Bell Inc., 593 F. Supp. 3d 855 (E.D. Wis. 2022).

82 Heath, F.4th at 662–63.

83 Id. at 662–64.

84 Id. at 663–64.

85 Id. at 664.

86 17-cv-02395, 2023 WL 5334621, at *1 (D. Kan. Aug. 18, 2023).

87 Id. at *12.

88 Id.

89 Id.

90 Id. at *11–12.

91 82 F.4th 595, 605–06 (8th Cir. 2023) (citation omitted).

92 Id.

93 SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1399.

94 Hennessy v. Mid-Michigan Ear, No. 21-cv-00301, 2023 WL 4676875, at *8 n.8 (W.D. Mich. July 21, 2023).

95 SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1400–01.

96 United States ex rel. Miller v. Reckitt Benckiser Grp. PLC, No. 15-cv-00017, Defendants’ Corrected Brief on the Impact of the Supervalu Decision and in Further Support of Defendants’ Motion To Dismiss Relator’s Fifth Amended Complaint, at * 10–11 (ECF No. 149) (W.D. Va. June 30, 2023) (quoting SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1400–01).

97 United States ex rel. Miller v. Reckitt Benckiser Grp. PLC, No. 15-cv-00017, United States’ Statement of Interest on the SuperValu Decision, at * 3 (ECF No. 150) (W.D. Va. July 7, 2023).

98 Id. (quoting SuperValu, 143 S. Ct. at 1399).

99 United States ex rel. Miller v. Reckitt Benckiser Grp. PLC, No. 15-cv-00017, 2023 WL 6849436, at *16–17 (W.D. Va. Oct. 17, 2023).

100 United States v. Regeneron Pharms., Inc., No. 20-cv-11217, Government’s Surreply to Regeneron’s Motion for Summary Judgment, at *8 (ECF No. 315) (D. Mass. June 8, 2023) [hereinafter, Regeneron, Government’s Surreply].

101 United States ex rel. Cairns v. D.S. Med. LLC, 42 F.4th 828, 834–36 (8th Cir. 2022) (analyzing Burrage v. United States, 571 U.S. 204, 210–13 (2014)); United States ex rel. Martin v. Hathaway, 63 F.4th 1043, 1052–53 (6th Cir. 2023) (same).

102 Regeneron, Government’s Surreply, at *8 (citing SuperValu, 143 S. Ct at 1402).

103 United States ex rel. Greenfield v. Medco Health Sols., Inc., 880 F.3d 89, 98–100 (3d Cir. 2018).

104 Martin, 63 F.4th at 1052–55; Cairns, 42 F. 4th at 834–36.

105 United States v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., No. 23-cv-08028, Judgment (1st Cir. Nov. 17, 2023) (granting petition to appeal).

106 United States v. Regeneron Pharms., Inc., No. 20-cv-11217, Memorandum & Order, at *21 (D. Mass. Sept. 6, 2023) (denying the government’s motion for partial summary judgment and finding the government must prove “but-for” causation) [hereinafter, Regeneron Decision]; United States v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., No. 20-cv-11548, Memorandum & Order, at *6–7 (D. Mass. July 14, 2023) (granting the government’s motion for partial summary judgment and finding that the government need only prove some “causal connection”) [hereinafter, Teva Decision].

107 United States v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., No. 20-cv-11548, Opp. to Government’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, at *16, n.8 (D. Mass. May 24, 2023).

108 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)(1)(A), (B).

109 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)(2)(B).

110 Id. § 1320a-7b(g) (emphasis added).

111 There have been at least a few courts that declined to require proof of causation. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Kester v. Novartis Pharm. Corp., 41 F. Supp. 3d 323, 332–35 (S.D.N.Y. 2014) (finding “Congress gave absolutely no indication … it intended … to limit the [FCA’s] reach where kickbacks were concerned” and that “any claim connected in any way to an [AKS] violation [is] ineligible for reimbursement”).

112 880 F.3d at 95.

113 Id. at 99.

114 See generally id.; see also 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(g).

115 Greenfield, 880 F.3d at 96–97.

116 Id. at 100 (emphasis added).

117 Cairns, 42 F.4th at 834.

118 Id. at 836 (emphasis added).

119 Id. at 834–36.

120 Id. at 834.

121 571 U.S. 204, 210–13 (2014); Cairns, 42 F.4th at 834.

122 Cairns, 42 F.4th at 835–36.

123 63 F.4th at 1052–55.

124 Id. at 1052–53.

125 Id. (citing Burrage, 571 U.S. at 210–11).

126 Martin, 63 F.4th at 1054–55.

127 144 S. Ct. 224 (2023).

128 See Regeneron Decision, at *21 (denying the government’s motion for partial summary judgment and finding the government must prove “but-for” causation); Teva Decision, at *6–7 (granting the government’s motion for partial summary judgment and finding that the government need only prove some “causal connection”).

129 Teva Decision, at *12–13.

130 913 F.3d 178, 190 (1st Cir. 2019) (citing Greenfield, 880 F.3d at 96–98).

131 Teva Decision, at *13.

132 Regeneron Decision, at *14 (citing Guilfoile, at 190).

133 See id. at *15–21.

134 Id. at *21.

135 United States v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., No. 20-cv-11548, Motion to Certify Interlocutory Appeal (D. Mass. July 26, 2023).

136 Id., Order (D. Mass. Aug. 14, 2023) (allowing defendant’s motion).

137 See United States v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., No. 23-cv-08028, Judgment (1st Cir. Nov. 17, 2023) (granting petition to appeal).

138 United States v. Regeneron Pharms., Inc., No. 20-cv-11217, Order (D. Mass. Oct. 25, 2023) (allowing plaintiff’s motion); No. 23-cv-08036, Judgment (1st Cir. Dec. 11, 2023).

139 No. 22-cv-03295, 2024 WL 1916749, at *6–8 (7th Cir. May 2, 2024).

140 Id. at *2.

141 Id.

142 Id. at *7.

143 Id. at *1.

144 Id. at *6–8.

145 Id. at *7.

146 Id.

147 Id.

148 Id.

149 See, e.g., Sayeed, 2024 WL 1916749, at *1, *6–8.

150 Cairns, 42 F.4th at 834–36 (analyzing Burrage, 571 U.S. at 210–13); Martin, 63 F.4th at 1052–53 (same).

151 143 S. Ct at 1402.

152 Regeneron, Government’s Surreply, at *8.

153 Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco, Remarks at the University of Oxford on the Promise and Peril of AI (Feb. 14, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-lisa-o-monaco-delivers-remarks-university-oxfordpromise-and [hereinafter, Monaco Remarks on AI].

154 Id.

155 U.S. Dep’t of Just., Fraud Section Year in Review – 2023, at 29 (Feb. 20, 2024), https://www.justice.gov/criminal/media/1339231/dl.

156 Id.

157 Exec. Order No. 14,110, 88 Fed. Reg. 75,191 (Nov. 1, 2023), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefingroom/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-ofartificial-intelligence/.

158 Id.

159 Id.

160 Id.

161 Monaco Remarks on AI.

162 Ctrs. For Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Frequently Asked Questions Related to Coverage Criteria and Utilization Management Requirements in CMS Final Rule (CMS-4201-F) (Feb. 6, 2024), https://www.ahcancal.org/Reimbursement/Medicare/Documents/CMS%20Memo%20FAQ%20on%202024%20MA%20Fin al%20Rule%202.6.24.pdf.

163 Id.

164 Id.

165 Id.

166 Id. The potential for bias in AI systems is widely acknowledged. See, e.g., Nat’l Inst. of Stand. & Tech., Towards a Standard for Identifying and Managing Bias in Artificial Intelligence, NIST Special Pub. 1270 (Mar. 2022) (“Bias is neither new nor unique to AI and it is not possible to achieve zero risk of bias in an AI system.”), https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1270.pdf.

167 Paul W. Grimm et al., Artificial Intelligence as Evidence, 19 NW. J. TECH. & INTELL. PROP. 9 (2021).

168 Id. at 62.

169 See Stephen D. Bittinger et al., Due Process: A Winning Weapon Against Extrapolated Overpayments, AM. HEALTH L. ASS’N (Apr. 11, 2024) (discussing these cases), https://marketingstorageragrs.blob.core.windows.net/webfiles/AHLA_FA_Briefing_Bittinger_Stewart_Yates_Phillips_4-11- 24.pdf.

170 MedEnvios Healthcare, Inc. v. Becerra, No. 23-cv-20068, 2024 WL 1252264, at *5 (S.D. Fla. Mar. 25, 2024) (quoting Glob. Home Care, Inc. v. Nat’l Gov’t Servs., No. M-11-116, 2011 WL 3668242, at *3 (HHS-DAB Jan. 11, 2011)).

/>i

/>i