As Americans are becoming increasingly aware, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of thousands of manufactured chemicals that have been used in industry and consumer products since the 1940s. PFAS have unique physical and chemical properties and are colloquially termed “forever chemicals” for their ability to persist in the environment and bioaccumulate in humans and animals. In response to research indicating that PFAS can cause adverse human health and environmental effects, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has undertaken a “whole-of-agency” approach to addressing PFAS contamination, which is focused on restricting dispersion, remediating contamination, and investing in research on PFAS risks and removal technologies.

In April 2024, EPA finalized two rules that represent a seismic shift in PFAS regulation, and that will potentially impose enormous costs on the regulated community, including public water systems. On April 10, EPA announced first-ever federal drinking water standards for PFAS under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). Just over a week later, on April 19, it announced the finalization of a rule listing two of the most widely used PFAS compounds – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) – as “hazardous substances” under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as the Superfund law. EPA has also proposed two PFAS-related rules under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).

At the state level, California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) adopted public health goals for PFAS and the state has enacted legislation concerning PFAS in food packaging, cookware, textiles, and cosmetics.

PFAS DRINKING WATER REGULATION

On April 10, 2024, EPA announced the final rule establishing a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) for six PFAS under the SDWA. NPDWRs are legally enforceable primary standards and treatment techniques that apply nationwide to public water systems. This final rule is the most significant step EPA has taken to prevent PFAS exposure in drinking water in accordance with its “whole-of-agency” approach.

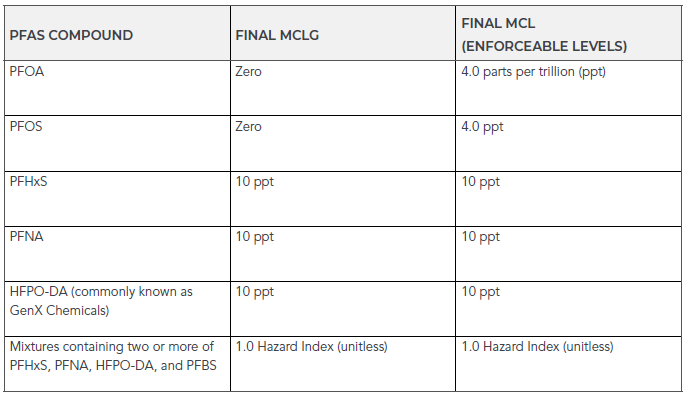

The final rule establishes enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) – concentrations of a contaminant that may not be exceeded in water delivered to any user of a public water system – for six PFAS: PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, PFHxS, and PFBS. The final rule also identifies a non-enforceable maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG) for each chemical. The rule also addresses mixtures containing two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS using a Hazard Index approach which requires a calculation to determine whether the cumulative effects of the combined PFAS compounds pose a potential risk. The finalized MCLs and MCLGs are as follows:

The MCLs of 4 ppt for PFOA and PFOS are set near the lowest level that current laboratory analytical methods can reliably detect the compounds. Further, the setting of the MCLGs for these compounds at zero reflects EPA’s determination that there is no level of exposure to PFOA or PFOS at which known or anticipated adverse health effects would not occur.

By 2027, public water systems subject to the rule must complete initial monitoring at all entry points to their distribution systems either biannually or quarterly depending on the size of the systems. Those systems which detect PFAS in drinking water above MCLs have an additional two years to implement solutions to reduce PFAS levels below MCLs.

The final rule also requires public water systems to notify customers of the initial monitoring results and ongoing monitoring results in Annual Water Quality Reports from 2027 onward. Violations of the rule will also require public notice beginning in 2027. Notification of a water standard violation must be provided to customers within 30 days, and notification of a testing or monitoring procedure violation must be provided within one year.

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS

To support the required cost-benefit analysis of the rule, EPA contends that the final rule will result in savings of $1.5 billion annually as a result of reduced adverse health effects stemming from PFAS exposure. On the other hand, numerous trade and lobbying organizations representing water utilities and local governments submitted comments in response to EPA’s March 2023 proposed NPDWR arguing that compliance costs would be significant because treating drinking water for PFAS would require utilities to install advanced technologies that carry an extraordinary cost. These astronomical expenses come at a time when water utilities and local governments are already facing increases in prices of essential supplies, equipment and electricity to maintain operations.

EPA estimates that between 4,100 to 6,700 public water systems serving a total population of 83 to 105 million people are currently exceeding one or more of the Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) established by this rule. The American Water Works Association, an organization whose membership includes 4,300 water utilities that supply roughly 80% of the nation’s drinking water, commissioned a PFAS National Cost Model Report which estimated that the cost to comply with the MCLs will exceed $3.8 billion annually.

IMPLEMENTATION AND COST OF COMPLIANCE

Many water systems are currently ill-equipped to meet the required MCLs as traditional water treatment technologies do not address PFAS. The final rule identified several treatment technologies such as granular activated carbon, anion exchange resins, reverse osmosis, and nanofiltration that have been shown to be effective at removing PFAS.

Although these treatment technologies are available, they are expensive. EPA estimates compliance with the rule will cost approximately $1.5 billion annually, in the form of water system monitoring, communicating with customers, and installing water treatment technologies where necessary. As noted above, opponents of the rule have asserted that costs associated with compliance will be much higher. An estimated 6% to 10% of the 66,000 public water systems will require significant investment in treatment systems to comply with the new MCLs.

To offset the cost, the federal government has dedicated $21 billion in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to drinking water related matters. Nine billion dollars are set aside specifically for communities dealing with PFAS contamination of drinking water, and the remaining $12 billion is allotted for general drinking water improvements including addressing PFAS chemicals.

NEXT STEPS

The final rule will become effective 60 days from the publication date in the Federal Register. A pre-publication version of the final rule is available here. Public water systems subject to the rule will need to take steps now to identify whether PFAS compounds are present in their systems and, if so, begin the process of planning for and implementing capital improvements to treat for PFAS, which will likely take several years to complete.

PFOA AND PFOS LISTED AS CERCLA HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES

On April 19, 2024, EPA announced that it is finalizing a rule to list PFOA and PFOS as “hazardous substances” under CERCLA. The move brings two of the most widely used PFAS compounds under EPA’s broad CERCLA purview and will enable the agency to investigate, remove, and remediate releases of the compounds, and to impose liability for the associated costs on “potentially responsible parties,” including current owners and operators of sites where the releases occurred, past owners and operators at the time of the releases, persons who arranged for the disposals of the hazardous substances, and persons who transported them to a site.

CERCLA imposes “strict liability” meaning that identified potentially responsible parties can be held liable regardless of any fault and regardless of whether they complied with all applicable laws. Further, liability to the government and non-liable private parties is “joint and several” so that each individual party can potentially be held responsible for all of the investigation, removal, and remediation costs regardless of the magnitude of their contribution to the problem (subject to potential divisibility and allocation arguments where applicable).

The listing of PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances will likely lead EPA to designate new Superfund Sites and re-open closed sites. It may also expose potentially responsible parties to vast liability for the costs of investigating and remediating the widespread occurrence of PFAS in the environment. These consequences will be felt particularly strongly in California which has approximately 12,000 known PFAS-contaminated sites. Among other consequences, it is likely to add complexity to real estate sale and leasing transactions where buyers and lenders will have increased reason to investigate and seek to avoid potential exposure to liability associated with PFAS contamination.

EPA LOOKS TO EXPAND RCRA CORRECTIVE ACTIONS TO INCLUDE PFAS

On February 8, 2024, EPA proposed two rules to amend RCRA regulations to expand the definition of “hazardous waste” as it applies to “corrective action” (which entails environmental investigation and cleanup), and to designate nine types of PFAS and their salts and structural isomers as “hazardous constituents.”

HAZARDOUS WASTE AND HAZARDOUS CONSTITUENTS

In order to understand the proposed new rules, it is useful to review briefly the way EPA currently regulates “hazardous wastes” and “hazardous constituents.”

Under Subtitle C of RCRA, EPA regulates hazardous waste from its generation to its ultimate disposal, commonly referred to as “cradle to grave” regulation. One way in which EPA regulates hazardous waste is by issuing permits to hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs). These permits include corrective action provisions that require TSDFs to investigate and clean up releases of hazardous waste. In order for a material to be classified as a hazardous waste under Subtitle C, it must first be a solid waste, a term that is defined very broadly. Under these regulations, a solid waste is also classified as a hazardous waste if it exhibits one or more specific characteristics (ignitability, corrosivity, reactivity, or toxicity) or if EPA has specifically listed it as a hazardous waste. Thus, hazardous wastes are often referred to as either “characteristic” or “listed” wastes.

EPA also maintains a list of “hazardous constituents” in Appendix VIII, 40 C.F.R. Part 261. A hazardous constituent is a substance that has toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic effects on humans or other life forms. The listing of a hazardous constituent in Appendix VIII does not make the chemical a hazardous waste and thus subject to the broad requirements of Subtitle C. However, any permit issued by EPA to a TSDF must require corrective action for all releases of hazardous wastes or hazardous constituents.

EPA’S PROPOSAL TO CLARIFY CORRECTIVE ACTION AUTHORITY

The first proposed rule would modify the RCRA regulations applicable to TSDFs with regard to EPA’s corrective action authority. Specifically, the proposed rule would amend the definition of hazardous waste applicable to corrective actions to expressly apply RCRA’s broader statutory definition of hazardous waste instead of the narrower regulatory definition, which is generally limited to characteristic and listed wastes. The RCRA statute defines hazardous waste broadly as a solid waste that may “(A) cause, or significantly contribute to an increase in mortality or an increase in serious irreversible, or incapacitating reversible, illness; or (B) pose a substantial present or potential hazard to human health or the environment when improperly treated, stored, transported, or disposed of, or otherwise managed.” 42 U.S.C. § 6903(5) (A), (B). This amendment would allow EPA to use its corrective action authority to address emerging contaminants, such as PFAS, as well as other non-regulatory waste at RCRA permitted TSDFs.

This proposed change stems from efforts by the New Mexico Environment Department to address PFAS contamination at Canon Air Force Base in Curry County, New Mexico. The base was the site of PFAS releases to the environment caused by the use of aqueous film-forming foam for firefighting training. PFAS-contaminated groundwater migrated to nearby dairy farms and required dairy farmers to euthanize several thousand cows due to adulterated milk. The Department’s response was to include provisions in the Base’s renewed Corrective Action Permit that define “hazardous waste” according to RCRA’s broad statutory definition, rather than the narrower definition found in EPA’s regulations. The Trump Administration’s Justice Department, acting on behalf of the United States Air Force, challenged the provisions in the renewed Corrective Action Permit in federal district court. The court dismissed the case on jurisdictional grounds. The United States appealed that decision to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. The appeal is now pending. It is unclear if, or how, the United States will proceed with the appeal given that the rule the Biden Administration’s EPA has now proposed is at odds with the position the Trump Administration’s Department of Justice took in the trial court. After numerous extensions, the United States’ opening brief on appeal is due June 28, 2024.

PROPOSAL TO LIST NINE PFAS AS “HAZARDOUS CONSTITUENTS” UNDER RCRA

EPA’s second proposed rule would list nine PFAS, their salts, and their structural isomers as RCRA hazardous constituents in Appendix VIII, 40 C.F.R. Part 261. Those substances are:

- Perfluorooctanoic acid

- Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid

- Perfluorobutane sulfonic acid

- Hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid

- Perfluorononanoic acid

- Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid

- Perfluorodecanoic acid

- Perfluorohexanoic acid

- Perfluorobutanoic acid

Similar to the first proposal, the principal impact of adding nine PFAS as hazardous constituents to Appendix VIII would be to expand the scope of EPA’s Corrective Action Program. RCRA requires corrective action for all releases of hazardous waste or hazardous constituents from solid waste management units at a permitted facility. 42 U.S.C. § 6924(u). Thus, this proposal would require EPA and state agencies implementing an EPA-authorized hazardous waste program to consider the presence of these nine PFAS when implementing corrective action requirements at hazardous waste TSDFs.

IMPACT ON THE REGULATED COMMUNITY

Taken together, the revised Corrective Action rule and the PFAS Hazardous Constituent rule are likely to increase the number and scope of PFAS-related corrective actions at hazardous waste TSDFs. EPA indicates that nearly 50% of potentially affected facilities pertain to chemical manufacturing and waste management and remediation services. Other potentially impacted facilities include metal manufacturers and fabricators, coal manufacturers, and petroleum refineries. EPA also clarified that the PFAS Hazardous Constituent rule would apply only to facilities that are hazardous waste TSDFs. Facilities such as publicly owned treatment works, for example, would be excluded.

The proposal to list the nine PFAS as hazardous constituents potentially signals EPA’s intent to eventually list certain PFAS as hazardous waste, which would subject facilities to the Subtitle C’s cradle-to-grave regulatory scheme. Classifying PFAS as hazardous waste under RCRA would also subject facilities with PFAS contamination to cost recovery and contribution causes of action under CERCLA, assuming that the same PFAS constituents are eventually treated as CERCLA “hazardous substances” – the subject of the ongoing rulemaking that began in 2022.

Finally, if EPA were to finalize the PFAS Hazardous Constituent rule and the Corrective Action rule, citizen suits would likely follow. By adding PFAS as a hazardous constituent and clarifying that corrective actions now encompass hazardous constituents, TSDFs could be subject to citizen suits if they improperly handle PFAS waste or the release of PFAS waste presents an imminent and substantial endangerment to public health or welfare or to the environment.

CALIFORNIA ADOPTS PUBLIC HEALTH GOALS FOR PFOA AND PFOS IN DRINKING WATER

Days before EPA issued its nationwide drinking water standards for select PFAS, on April 5, 2024, California’s OEHHA adopted Public Health Goals (PHGs) for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water at 0.007 ppt and 1.0 ppt, respectively.

A PHG is the level of a drinking water contaminant at which adverse health effects are not expected to occur from a lifetime of exposure. Like MCLGs at the federal level, PHGs are non-enforceable advisory levels. However, PHGs reflect the State’s current assessment of the risk a particular contaminant poses to public health. PHGs also function as precursors to enforceable MCLs. Under California’s Calderon-Sher Safe Drinking Water Act, essentially California’s analogue to the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, OEHHA must adopt PHGs for each contaminant for which California’s State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) proposes to adopt an MCL. California state law requires the SWRCB to establish an MCL as close to a PHG as is technologically and economically feasible, with a primary emphasis on protecting public health.

Importantly, California’s MCLs cannot be less stringent than EPA’s federal MCLs. Assuming the final rule becomes effective, EPA’s MCLs of 4.0 ppt for PFOA and PFOS represent the regulatory floor for California. The SWRCB will have to propose MCLs at those levels or lower, which are already near analytical detection limits.

CALIFORNIA LEGISLATION ADDRESSING PFAS

In 2023, two California bills addressing the use of PFAS chemicals in various consumer products took effect. The first, Assembly Bill (AB) 1200, took effect on January 1, 2023, and prohibits the sale of food packaging containing PFAS and requires the manufacturer to use the least toxic alternative. The bill also requires that, as of January 1, 2024, all cookware which includes designated PFAS, among a list of other chemicals, must be labeled accordingly when sold. Additionally, AB 652, which took effect on January 1, 2023, bars the manufacture, distribution or sale of any new product for juveniles containing PFAS. The law uses a broad definition of PFAS and covers “intentionally added PFAS” or PFAS at concentrations above 100 parts per million (ppm) in the product.

AB 1817 and AB 2771, which prohibit the manufacture, distribution, and sale of certain “textile articles” containing PFAS and cosmetic products containing intentionally added PFAS, respectively, will both take effect on January 1, 2025.

AB 1817 bans the manufacture, distribution, sale, or offer for sale of a new textile article that contains regulated PFAS. AB 1817 defines regulated PFAS to mean PFAS that a manufacturer has intentionally added for a functional or technical effect or PFAS that exceeds a certain threshold. Commencing on January 1, 2025, the threshold is 100 ppm and decreases to 50 ppm on January 1, 2027. This bill applies to a wide variety of products, as the bill defines “Textile Articles” as “Apparel,” i.e., clothing intended for regular wear or formal occasions; outdoor apparel; handbags; and backpacks and household items such as shower curtains, bedding, towels, and tablecloths. Notably, AB 1817 will allow retailers and distributors to rely in good faith on certificates of compliance provided by manufacturers.

AB 2771 bans the manufacture, sale, delivery, holding, or offering for sale in commerce of any cosmetic product that contains intentionally added PFAS. AB 2771 defines “intentionally added” to mean either (1) PFAS chemicals that a manufacturer has intentionally added to a product and that have a functional or technical effect on the product or (2) PFAS chemicals that are “intentional breakdown products” of an added chemical. AB 2771 also defines “cosmetic product” to mean an article for retail sale or professional use intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering appearance.

/>i

/>i