On August 28, Judge Stephen V. Wilson of the Central District of California, entered the latest ruling in the ongoing saga of the COVID-19 business interruption coverage dispute between celebrity plaintiff’s attorney Mark Geragos and Insurer Travelers.

The case, 10E, LLC v. The Travelers Indemnity Co. of Connecticut was filed in state court. Travelers removed to federal court, where Geragos sought remand and Travelers moved to dismiss. Judge Wilson denied remand and granted the Motion to Dismiss, finding plaintiff did not satisfactorily allege the actual presence of COVID-19 on insured property or physical damage to its property. This holding is inconsistent with long standing principles of California insurance law and appears to improperly enhance the minimal pleading threshold under Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 678 (2009) (To survive a motion to dismiss, a complaint need only allege a claim “that is plausible on its face.”).

After rejecting Geragos’ attempt to have the case remanded based on a finding that Geragos had fraudulently joined a defendant to avoid removal, the Judge proceeded to the Motion to Dismiss which raised three issues: (1) the effect of the Virus Exclusion in the Travelers’ Policy, (2) whether plaintiff failed to allege that the governmental orders prohibited access to its property, and (3) whether plaintiff could “‘plausibly allege that it suffered ‘direct physical loss or damage to property’ as required for civil authority coverage.’” Rather than address the effect of the exclusion, which would be the narrowest issue (this exclusion is not present in all policies), the Court proceeded directly to the third issue, which has the broadest potential application.

Courts applying California law to insurance disputes typically review the core principles of insurance construction. At its most basic, these principles entail the bedrock concept that any reasonable ambiguity must be construed in favor of achieving the objective of the insurance contract – providing insurance. However the Court did not refer to this principle, instead briefly stating that it “must give terms their ordinary and popular usage, unless used by the parties in a technical sense or a special meaning is given to them by usage.” (at page 6.)

Having set an incomplete and inaccurate prism for viewing the issues, the Court proceeded to what it saw as the core question – whether the policyholder’s inability to use its restaurants amounted to “direct physical loss or damage to property.” The Court determined that it did not, holding that the phrase required the property to undergo a “distinct, demonstrable, physical alteration,” rather than “impairment to an economically valuable loss of use of property,” citing MRI Healthcare Ctr of Glendale, Inc. v. State Farm, 187 Cal. App. 4th 766,779 (2010) for this proposition. MRI involved an MRI machine which stopped functioning when it was turned off, and the policyholder had attempted to attribute this malfunction to a rain event occurring far earlier. The Court’s reliance on MRI Healthcare was incorrect for various reasons, including the fact that wording is key and MRI’s policy language only covered “loss” not “loss or damage,” a distinction essential to the policy construction issues here.

Applying this incorrect standard, the Court then held that “Plaintiff only plausibly alleges that in-person dining restrictions interfered with the use or value of its property – not that the restrictions caused direct physical loss or damage.” (at page 7.) The court stated:

Plaintiff’s FAC appears to suggest that Plaintiff’s business hardships resulted from the physical action of the novel coronavirus itself, which “infects and stays on surfaces of objects or materials . . . for up to twenty-eight days.” Id. at 4. However, Plaintiff does not allege that the virus “infect[ed]” or “stay[ed] on surfaces of” its insured property. Whatever physical alteration the virus may cause to property in general, nothing in the FAC plausibly supports an inference that the virus physically altered Plaintiff’s property . . . . (emphasis added)

In other words, while sufficient allegations of damage might have satisfied the Court’s (incorrect) view of the pleading threshold, plaintiff did not make the requisite allegations and failed to satisfy the (incorrect) standard (a finding that presumably other plaintiffs may be able to satisfy).

The Court went on to write that even if plaintiffs could have established physical loss or damage, it failed to show “direct” causation. But “direct” is another way of referring to “proximate cause,” which California courts routinely find to be a jury question and not subject to resolution by a motion to dismiss.

Finally, the Court rejected the Policyholder’s argument that the presence of the disjunctive “or” in the phrase “direct physical loss of or damage to” required different meanings for the two terms, one of which would be impaired use, an argument relying on Intermodal Services, Inc. Travelers Prop Cas. Co. of Am., 2018 WL 3829767 (C.D. Cal. 2018). The Court distinguished that case as being limited to the situation where there was a “permanent dispossession of something” which was not the present case where “Plaintiffs remained in possession of its dining room, etc.” (at page 8.)

In rejecting this argument, the Court misreads the thrust of Intermodal which, at its core, addresses loss of the use of the property. While Intermodal involved property being lost in transit, other cases have reached the same result where property was stolen,[1] inaccessible,[2] or the loss of functionality for its intended purpose,[3] or unavailable for any other reason, these are just different ways of stating the overarching concept that what matters to the Policyholder is that it cannot use the property. It bears repeating that Policyholder need not establish that one or another of these meanings is the only meaning but just that it is a reasonable meaning.

Since these are all reasonable meanings of the term “loss,” and the Court’s approach created a redundancy which courts strive to avoid (here, physical loss equating to physical damage), it is apparent how the Court’s adoption of an incorrect standard necessarily led to an incorrect conclusion.

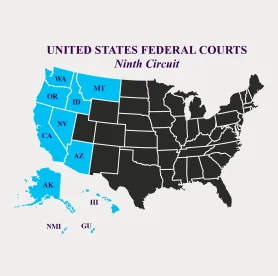

While the Court may not have been aware of the recent District Court decision in My Choice Software, LLC. v. Travelers Cas. Ins. Co., 2020 WL 4814235 (9th Cir. Aug. 19, 2020), this decision provides an independent basis for requiring a different outcome. The fact that another district court judge reached a different outcome under the same policy wording renders the policyholders’ interpretation reasonable, per se. Specifically, while a court is not bound by decisions in other jurisdictions, the fact that other judges have construed a term in a certain way supports the reasonableness of that view.[4] Insurers are hard pressed to object to this principle since they frequently cite it when defending their own conduct in bad faith cases.[5]

In short, this Court’s view of how California courts would resolve the issue is fundamentally flawed in numerous respects. Recapping:

-

The Court viewed the case through an incorrect prism, which ignored bedrock principles of California insurance policy construction.

-

Insurance cases turn on the contract wording, and the Court incorrectly based its analysis on a case with different language (only using the phrase “loss,” not “loss or damage”), leading it in a direction contrary to California law.

-

While the Court correctly observed that the disjunctive requires that “loss” means something different than “damage,” it proceeded to construe the terms as synonymous, effectively rendering the two phrases redundant which similarly is contrary to California law. It ignored numerous cases from around the country which provided meanings for “loss,” which were different than “damage” and which did not require physical alteration.

-

Under California law, “direct” is synonymous with proximate cause and should be a jury question.

[1] See, e.g., Mangerchine v. Reaves, 63 So.3rd 1049, 1056 (La. 2011); Corbian v. U.S. Auto Ass’n, 20 So. 3rd 601, 612 (Miss. 2009).

[2] See, e.g., Murray v. State Farm, 509 S.E.2nd 1 (W. Va. 1998); Manpower Inc. v. ICSOP, 2009 U.S. Dist. Lexis 108626 (E.D. Wis. Nov. 3, 2009); Western Fire Ins. Co. v. First Presbyterian Church, 165 Colo. 34 (1968); Matzner v. Seaco Ins. Co., 1998 WL 566658 (Mass. Super. Aug. 12, 1998).

[3] See, e.g., Wakefern v. Liberty Mutual Fire Ins. Co., 968 A.2d 724 (N.J. 2009); Hughes v. Potomac Ins. Co., 18 Cal. Rptr. 650 (1962); Southeast Mental Health Ctr., Inc. v. Pacific Ins. Co., 439 F. Supp. 2d 831 (W.D. Tenn. 2006); General Mills, Inc. v. Gold Medal Ins. Co., 622 N.W.2d 147, 152 (Minn. Ct. App. 2001); Pepsico, Inc. v. Winterthur Int’l Am. Ins. Co., 806 N.Y.S. 2d 709, 711 (2005); Dundee Mut. Ins. Co. v. Marifjeren, 587 N.W.2d 191, 194 (N.D. 1998).

[4] See, e.g., Thomas v. Mut. Ben Health & Acc Ass’n, 123 F. Supp. 167, 171 (S.D.N.Y. 1954), aff’d sub nom, Thomas v. Mut. Benefit Health & Accident Ass’n, 220 F.2d 17 (2d Cir. 1955); Walker v. Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co., 268 F. Supp. 899, 901 (D. Mont. 1967).

[5] See, e.g., Aetna Cas. & Sur. Co. v Super. Ct. of Ariz., 778 P.2d 1333, 1336 (Ariz. Ct. App. 1989); Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Fed. Ins. Co., 2011 WL 1237611, at *7 (S.D. Ohio Mar. 30, 2011).

/>i

/>i