Categorizing data as “sensitive” is a common feature in U.S. state privacy law, as well as the EU’s GDPR (which uses the term “special category” for similar personal data).[1] What is considered sensitive data varies from state to state, as well as the obligations that come with it. Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, Montana, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia all require consent for the collection of sensitive data, as well as some form of a data privacy impact assessment to be conducted concerning that collection.[2] Iowa and Utah give sensitive data extra opt-out rights that don’t necessarily attach to regular personal information.[3] California gives residents certain rights to limit the use of their sensitive data.[4] Processing large amounts of special categories of data under the GDPR requires not only a data privacy impact assessment[5] but also that the controller appoint a Data Protection Officer.[6]

All of these jurisdictions vary in their definitions of sensitive data. For example, while every jurisdiction considers a person’s ethnic origin to be sensitive data, only Oregon includes a person’s national origin as sensitive data. Biometric data is only sensitive in most jurisdictions if it is used to uniquely identify a data subject, but in Colorado it is considered sensitive if it may be used to uniquely identify a data subject.[7] The industry-best-practice privacy frameworks aren’t clear or consistent on the definition of sensitive data, either. While ISO 27701 and 29100 consider sensitive data to be any category of personal information “whose nature is sensitive” or that might have a significant impact on a data subject, the NIST Privacy Framework does not refer to sensitive personal information at all.

One of the biggest areas of divergence in defining sensitive data involves the treatment of information pertaining to sexuality and gender. This article examines the differences in how the modern privacy statutes have defined sensitive data to include sexuality and gender-related concepts. Section I explains the different sexuality and gender terminology used by the states. Section II explains the common, and legal, differences in those terms. Section III attempts to apply those terms to real-world scenarios.

Section I. What the states consider “sensitive.”

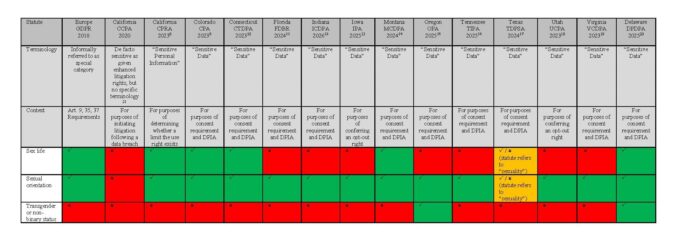

As shown in the below chart, most jurisdictions consider sexual orientation to be sensitive data, whereas about half, including the GDPR, consider a data subject’s “sex life” to be sensitive data. Texas’s statute uniquely refers to “sexuality” as a category of sensitive data in place of more common terminology. Oregon and Delaware stand alone in adding transgender and nonbinary status to their definitions of sensitive data. That prompts the question – have the states effectuated the same protections around gender and sexuality?

Click to view full-sized table.

Section II. Common and legal meanings.

When it comes to defining terms, words don’t always have the same meaning in common parlance as they do in the law. Often, they don’t even have the same meaning from person to person in common parlance, either. The difficulty in that comes when a term is used in a statute but not defined by other laws or judicial rulings, leaving the term up to interpretation.

The end-result is that while the modern privacy statutes seek to effectuate heightened protections around sensitive data and may facially appear to be doing the same thing, they may be producing different results when it comes to gender identity, sexuality, and the like. The following attempts to explain what each term used within the modern statutes does, and does not, mean.

Sex life

“Sex life” is commonly understood to mean “a person’s sexual activities.”[22] While it likely varies in what it means person to person, it generally seems to pertain to sexual acts. In all of the states that refer to sex life as sensitive data, none have a statutory or caselaw definition of the term.

Sexual orientation

“Sexual orientation” is considered “a person’s sexual identity or self-identification as bisexual, straight, gay, pansexual, etc.;”[23] this is generally understood to be irrespective of a person’s own gender identity.[24]

Although not defined within the CPRA, California has many statutes that legally define sexual orientation as meaning “heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality.”[25] Tennessee has a similar definition in a law concerning family life curriculum, adding only “actual or perceived” before “heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality.”[26]

Other states are not so straightforward. Colorado does not define sexual orientation in its privacy laws, but it does have multiple legal definitions of sexual orientation throughout its code. For example, in the criminal context, sexual orientation “means a person’s actual or perceived orientation toward heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality, or transgender status.”[27] The Civil Rights division, however, defines sexual orientation as “an individual’s identity, or another individual’s perception thereof, in relation to the gender or genders to which the individual is sexually or emotionally attracted and the behavior or social affiliation that may result from the attraction.”[28] It remains unclear which definition, if any, would attach to “sexual orientation” for purposes of sensitive data under the Colorado Privacy Act. Notably, Colorado’s privacy statute does not reference transgender status, so adoption of the former definition would effectively broaden the definition of sensitive data.

Sexuality

Most ambiguous of all may be the term “sexuality,” which is only used in the Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPSA), set to take effect in 2024. Sexuality is generally understood to be the “feelings and activities connected with a person’s sexual desires.”[29] To some, sexuality might implicate sexual orientation, while to others, it may strictly relate to acts of sex or sexual health. And to some, sexuality may carry a connotation of excessiveness.[30]

Despite including sexuality in its definition of sensitive data, neither the TDPSA nor other Texas-statutes provide a legal definition of “sexuality,” nor does caselaw clarify the term. Therefore, whether a particular aspect of a data subject’s sexuality – including status as transgender or nonbinary – is considered to be within or outside of the scope of the term remains to be seen.

Status of transgender or nonbinary

“Transgender” is defined commonly as “denoting or relating to a person whose gender identity does not correspond with the sex registered for them at birth,” whereas “nonbinary” typically is defined as “denoting, having, or relating to a gender identity that does not conform to traditional binary beliefs about gender, which indicate that all individuals are exclusively either male or female.” Neither of these definitions are commonly understood to be related to sexual orientation; they only describe the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the sex assigned to them at birth.[31] That said, and as discussed above, some state statutes, such as the criminal statute in Colorado, group “transgender” as a subcategory of sexual orientation.

As mentioned, Oregon and Delaware are the only states explicitly to include transgender and nonbinary status in their definitions of sensitive data.[32] Oregon does not proffer a legal definition of either transgender or nonbinary. In a miscellaneous definition section with broad applicability to all state laws, however, the term “gender identity” is defined as “an individual’s gender-related identity, appearance, expression or behavior, regardless of whether the identity, appearance, expression or behavior differs from that associated with the gender assigned to the individual at birth.”[33] Delaware is similar in that it does not have a statutory definition for the term “transgender,” but it does have several statutes consistently defining “gender identity” as “a gender-related identity, appearance, expression or behavior of a person, regardless of the person’s assigned sex at birth.”[34] These definitions of “gender identity” appear to contemplate transgender status, but the connection is not explicit by statute.

On the opposite end of Oregon, states like Montana have made efforts to make the applicability of its laws to transgender and nonbinary status a legal impossibility. In April 2023, the Montana state legislature passed SB 458, which created a definition of “sex” that effectively renders transgender and nonbinary individuals legally unrecognizable.[35] The bill also methodically amended over 40 statutes to apply this new definition of “sex” throughout the state’s code. This implies that any interpretation of “sex life” and “sexual orientation” to incorporate transgender or nonbinary status for the purposes of the extra obligations imposed on sensitive data would be highly improbable.

Section III. Real world implications.

In practice, courts may struggle with how to interpret these terms when determining what is – and is not – sensitive data.

For example, gender identity, which is commonly understood to mean “a person’s internal sense of being male, female, some combination of male and female, or neither male nor female,” may be sensitive or non-sensitive data depending on the state and the context.[36] For example, in Oregon and Delaware, a person’s gender identity would not be sensitive data if it matches their biological gender assigned at birth because that person does not meet the definition of transgender or nonbinary status. A person whose gender identity does not match their biological gender assigned at birth would qualify as having transgender or nonbinary status, in which case their gender identity may be sensitive data. Additionally, in the latter case, a transgender or nonbinary person’s biological gender assigned at birth may then be qualified as sensitive data, too, because that information, combined with their gender identity, would reveal their transgender or nonbinary status. In a state such as Montana, gender identity would never be considered sensitive data because its privacy law only categorizes sexual orientation as sensitive data, and sexual orientation does not necessarily reveal a person’s gender identity if terms such as “homosexual,” “heterosexual,” and “bisexual” are used.

Internet content subscription services that primarily provide sexually explicit content may also pose tough questions for courts. In states that have included “sex life” in the definition of sensitive data, user activity on these sites may qualify as sensitive data. Given the lack of a legal definition of sex life, courts will have to determine whether and what kind of activities (such as whether viewing pornographic material) does or does not constitute a part of an individual’s sex life.

Similar questions may arise in cases involving “revenge porn,” which is “sexually explicit images of a person posted online without that person’s consent especially as a form of revenge or harassment.”[37] Take Texas, for example, which does not have a statute criminalizing revenge porn[38] but has included the term “sexuality” under sensitive data for its data privacy law. With sexuality having a broad meaning in common language, but lacking a legal definition thus far under Texas law, courts might construe revenge porn to constitute sensitive data thus mandating consent. In such a case, it remains an open question whether a court might attempt to apply the Texas statute to a website that hosts the sexually explicit materials for failing to obtain the consent of the subject of the materials. In some other states, it’s possible that the storage or publication of pornographic materials might trigger the consent requirements under the state privacy statute, but only if the images implied the data subject’s sexual orientation (e.g., Indiana and Iowa). The net result is that different states are likely to lead to different outcomes despite seemingly similar laws.

Additional scenarios highlighting these differing terms and obligations are certain to arise.

[1] GDPR, Art. 9.

[2] Col. Rev. Stat. §§ 6-1-1308(7), 6-1-1309(2)(c) (2023); Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §§ 42-520(a)(4), 42-522(a)(4) (West); Florida S.B. 262, §§ 501.71(2)(d), 501.713(1)(c)(4)(d) (2023); Indiana Senate Act No. 5, IC §§ 24-15-4-1(5), 24-15-6-1(b)(4) (2023); Montana S.B. 384, §§ 7(2)(b), 9(1)(d) (2023); Oregon Senate Bill 619, §§ 5(2)(b), 8(1)(b)(B) (2023); Tennessee Amd. No. 1 to H.B. 1181, §§ 47-18-3204(a)(6), 47-18-3206(a)(4) (2023); Texas H.B. No. 4, §§ 541.101(b)(4), 541.105(a)(4) (2023); Va. Code §§ 59.1-578(A)(5), 59.1-580(A)(4).

[3] Iowa S.B. 262 § 715D.4(2); Utah Code § 13-61-302(3)(a).

[4] Originally, the CCPA did not address sensitive data in the same way as other U.S. state privacy laws beyond giving residents enhanced litigation rights in the event of a breach. (Cal. Civ. Code 1798.150(a)(1) (West 2021) (incorporating by reference data fields referred to in Cal. Civ. Code 1798.81.5(d)(1)(A))). However, the CPRA puts forth a definition of “sensitive personal information” and imposes additional notice requirements and use limitations for data that falls under that definition. (Cal. Civ. Code 1798.140(ae)(1), (2) (West 2021)).

[5] GDPR Art. 35 § 3(b).

[6] GDPR Art. 37 § 1(c).

[7] Col. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1303(24)(b).

[8] Cal. Civ. Code 1798.140(ae)(1), (2) (West 2021).

[9] Col. Rev. Stat. § 6-1-1303(24)(a).

[10] Conn. Substitute Bill No. 6, § 1(27).

[11] Fla. S.B. 262, § 501.702(31) (a)-(d) (2023).

[12] Ind. Senate Act No. 5, IC § 24-15-.5(28) (2023).

[13] Iowa S.B. 262 § 715D.1(26).

[14] Mont. S.B. 384, § 2(24) (2023).

[15] Or. S.B. 619, §1(18) (2023).

[16] Tenn. Amend. No. 1 to H.B. 1181, § 47-18-3201(26) (2023).

[17] Tex. H.B. No. 4, § 541.001(29) (2023).

[18] Utah Code § 13-61-101(32)(a).

[19] Va. Code § 59.1-571.

[20] Del. H.B. 154, § 12D-102(30).

[21] Cal. Civ. Code 1798.150(a)(1) (West 2021) (incorporating by reference data fields referred to in Cal. Civ. Code 1798.81.5(d)(1)(A)).

[22] See Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries definition of “sex life.”

[23] See Merriam-Webster definition of “sexual orientation.”

[24] See “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Definitions,” Human Rights Campaign.

[25] See, e.g., Cal. Penal Code § 11410(b)(7) (West), and Cal. Educ. Code § 66262.7 (West).

[26] Tenn. Code Ann. § 49-6-1301(16) (West).

[27] Col. Rev. Stat. § 18-9-121(4)(b) (establishing and classifying bias-motivated crimes).

[28] Col. Rev. Stat. § 24-34-301(24) (defining terms for purposes of enforcing anti-discrimination statutes).

[29] See Oxford Learner’s Dictionary definition of “sexuality.”.

[30] See Merriam-Webster definition of “sexuality.”

[31] See “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Definitions,” Human Rights Campaign.

[32] OR S.B.619 § 1(18)(a)(A), Delaware H.B. 154, § 12D-102(30)(a).

[33] Compare with Cal. Code Regs. tit. 10, § 2561.1 (providing legal definitions for terms such as “actual gender identity,” “perceived gender identity,” “transgender person,” and “gender transition”).

[34] See, e.g., Del. Code Ann. tit. 25, § 5141(13) (West) (defining terms in the Landlord-Tenant Code) and Del. Code Ann. tit. 6, § 4502 (West) (defining terms for purposes of equal accommodations).

[35] Compare with Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-21-102(20) (West) (similarly restricting the legal definition of “sex” to mean and only refer to the designation of a person as male or female in accordance with their birth certificate).

[36] See Merriam-Webster definition of “gender identity.”

[37] See Merriam-Webster definition of “revenge porn.”

[38] Compare with Fla. Stat. Ann. § 784.049 (West) (recognizing that an individual has a reasonable expectation of privacy in sexually explicit images taken with consent, and criminalizing the publishing of those images without consent).

/>i

/>i