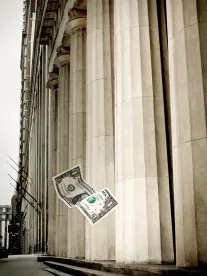

On March 12, 2015, Commerzbank AG, Germany’s second largest bank and a global financial institution, agreed to pay $1.45 Billion (yes, with a “B”) in forfeitures and fines to the U.S. Government for violating U.S. sanctions against Iran and Sudan. The amount paid by Commerzbank under the settlement will not be shocking to those who read our reporting on the BNP Paribas penalty of $8.9 Billion (again, that is a “B”) for similar sanctions violations.

Because the Commerzbank penalty follows on the heels of a sanctions violation by BNP Paribas (. . . and by ABN AMRO, and by Lloyds TSB, and by Credit Suisse AG, and by Barclays Bank PLC, and by ING Bank N.V., and by Standard Chartered, and by HSBC), the New York Superintendent of Financial Services, Benjamin Lawsky stated that “it highlights a potential broader problem in the banking industry.”

Commerzbank Allegedly Made a Bad Problem Far Worse

According to prosecutors, instead of focusing resources on compliance with U.S. sanctions regulations, Commerzbank choose to make efforts to avoid or evade sanctions, then to hide those efforts.

When the compliance software of Commerzbank New York began turning up sanctions and money-laundering red flags in transactions from its European counterparts, the European entities sought to reduce the red flags not by doing better diligence and desisting from prohibited transactions, but byhiding the transactions to which the U.S. entity objected. Between 2002 and 2008, Commerzbank used different measures, including stripping identifying information from transactions that would be prohibited to transit the U.S. financial system, to process 60,000 transactions on behalf of Sudanese and Iranian entities. Those transactions were valued at over $253 billion.

According to New York prosecutors, the overseas Commerzbank employees were unresponsive or uncooperative to requests for more information by those investigating the alerts. European employees felt the New York compliance personnel were “crying wolf” when they raised compliance issues.

According to the DOJ, in one particularly poignant email, a back office employee emailed other employees directing that, “if for whatever reason CB [Commerzbank] New York inquires why our turnover has increase[d] so dramatically, under no circumstances may anyone mention that there is a connection to the clearing of Iranian banks!!!!!!!!!!!!!.”

The Broader Problem

U.S. sanctions generally cover not only activities of U.S. persons, but also transactions that transit the U.S. financial system. One example common to recent enforcement actions is use U.S.-dollar clearing accounts. While some foreign parties have complained about the unfair extraterritorial application of U.S. sanctions, to the allegation in the Commerzbank case is that the company knowingly brought prohibited transactions into the U.S. financial system.

Whether or not one agrees with the aims or means of U.S. sanctions policy, it is clear that sanctions will apply to non-U.S. companies when their transactions take advantage of the U.S. financial system. It does not take a very long reach for the United States to penalize sanctions violations that walk right up to, and through, the font door. With that knowledge, companies that prepare themselves with protective compliance measures, then follow those compliance measures, will be best positioned to succeed in the global marketplace.

/>i

/>i