In a recent decision, a federal judge in Arizona vacated the Trump Administration’s Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR) and remanded the rulemaking back to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Order, in the case Pasqua Yaqui Tribe v. EPA, No. CV-20-00266, found that the Trump Administration’s definition of “waters of the United States” (WOTUS) had “fundamental, substantive flaws” that could not be fixed by remanding the NWPR to the agencies without also vacating the definition.

The Order caught many stakeholders off guard because EPA and the Army Corps already had announced plans to promulgate a new regulatory definition of WOTUS to replace the NWPR and asked the court to remand the NWPR to the agencies without vacatur so they would have time to craft the new definition. The court deemed that approach inappropriate, however, given that the agencies had made clear their “substantial concerns about certain aspects of the NWPR” including “the effects of the NWPR on the integrity of the nation’s waters” and the failure to account for “the effect ephemeral waters have on traditional navigable waters.” These were not “mere procedural errors or problems that could be remedied through further explanation,” the court explained. Per the court, they can only be cured through revising or replacing the definition of WOTUS, and thus vacatur was necessary to avoid significant environmental harm while the agencies develop their new definition.

Naturally, the court’s short Order has left many in the regulated community with urgent questions about how this might affect their activities. Below we respond to the questions that most project proponents are asking.

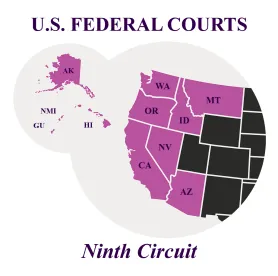

Is the NWPR vacated only in Arizona or is it vacated nationwide?

Although the Order did not specify the scope of the vacatur, EPA and the Army Corps quickly announced that they would no longer implement the NWPR nationwide.

What definition of WOTUS applies now?

As intimated in the court’s Order, the agencies will rely on the pre-2015 regulatory definition of “waters of the United States” until they promulgate their new WOTUS rule. Their reliance on the pre-2015 definition will once again be informed by the post-Rapanos guidance that confounded agency staff and the regulated community for years, resulting in widespread uncertainty and inconsistent determinations of the scope of Clean Water Act jurisdiction. The Arizona litigation also challenges a 2019 rule rescinding the 2015 Obama-era Clean Water Rule, which may be the subject of further proceedings, and (though unlikely) could result in judicial reinstatement of the 2015 Rule. Meanwhile, the period for any appeal of the recent order runs through the end of October 2021.

What impact does this have on the agencies’ plans to develop a new WOTUS definition?

Earlier this year, the EPA and the Corps announced a two-step approach to revising the WOTUS definition: (1) issue a rulemaking restoring the pre-2015 definition of WOTUS before either the Obama (2015) and Trump (2020) administrations’ revisions, and (2) replace it with a new definition of WOTUS. In light of the Arizona court’s Order, the agencies now can proceed directly to the second step. That may allow the agencies to issue their new WOTUS definition sooner and eliminates one basis that would have been available for challenging the Biden administration’s rulemaking process.

What impact does this have on my project?

The impact of the vacatur of the NWPR on ongoing and future-planned projects depends on where each project was in the development process on August 30, 2021, when the NWPR was vacated. Here are the most common scenarios:

-

Projects already permitted – Any project proponent that received a Clean Water Act permit premised on the NWPR may continue to rely on that permit until its expiration date regardless of whether construction activities have already begun. As always, the Army Corps still may modify or revoke a permit in response to subsequent changes to the proposed project or the environmental setting of the project, as well as for compliance-related reasons.

-

Projects with Approved Jurisdictional Determinations (AJDs) – As recently confirmed by the Army Corps, project proponents who received an AJD premised on the NWPR may continue to rely on it for five years from the date it was issued regardless of whether the project proponent already has obtained a Clean Water Act permit based on that AJD. This is consistent with longstanding Army Corps policy that AJDs are governed by the regulations in effect at the time they are issued. On the other hand, any AJDs that were pending on or issued after August 30, 2021, are governed by the pre-2015 definition of WOTUS. As always, the Army Corps still may modify an AJD if warranted for reasons unrelated to a regulatory change.

-

Projects with Preliminary Jurisdictional Determinations (PJDs) – Project proponents who received a PJD before or after August 30, 2021, may continue to rely on it. PJDs have no expiration date because they are premised on the conservative assumption that any hydrologic feature occurring on a property is subject to Clean Water Act jurisdiction. As a result, changes to the WOTUS definition do not affect the scope of jurisdictional features identified in a PJD.

/>i

/>i