During every presidential transition, the futures industry looks for clues regarding what changes may be coming. History has shown that when administrations transition, far more stays the same than changes and that the direction of new Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) Commissioners and Directors can be surprising. But this year, the industry may have more clues than normal. This article assembles some of the available information to illuminate, to the degree possible, potential changes in the enforcement activity of the CFTC. Two significant factors aid that exercise. First, President Donald Trump is the second US president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the only one to do so recently. Accordingly, four years of activity by the Division of Enforcement (DOE) under the Trump administration are available for examination and comparison to the intervening four years under a different administration. Second, during the prior four years, CFTC Commissioners have been unusually outspoken regarding their views on enforcement actions in the form of dissents and separate opinions. Presuming the Commissioners transitioning from the minority to the majority of the Commission will be more likely to shape the enforcement regime to reflect those views, prior statements of the soon-to-be-majority party Commissioners provide additional guidance on the potential coming priorities at the CFTC.

Of course, a number of important variables could confound this guidance. In particular, a new Chairman and Director of the DOE could have the greatest influence on the path ahead, and at this point, neither seat is filled. Still, as set forth below, the available record suggests that (1) Enforcement will remain active; (2) fraud and manipulation will remain priorities; (3) technical violations, such as data reporting, may decline; and (4) enforcement priorities related to cryptocurrencies and decentralized finance (DeFi) will likely be different.

CFTC Enforcement Reviews

Generally, the DOE publishes the results of its enforcement activity annually. From 2018 through 2020, this took the form of an Annual Report of the Division of Enforcement.1 In 2017, 2022, 2023, and 2024, it released its "Annual Enforcement Results" as a press release with an addendum of statistics.2 Although no comprehensive summary of the enforcement cases brought was published for 2021, the CFTC published an Agency Financial Report, which provided extensive financial data and included some summary enforcement statistics.3 The absence of data from 2021 is noted below where relevant. These annual summaries tend to describe the accomplishments of the year's enforcement activity, statistics regarding the categories of cases resolved and total fines and total financial penalties imposed. Although the format and method of presentation change among the styles of documents and their form, they provide a reasonable basis to compare activity in the Division across years.

Separate Commissioner Statements

The DOE most often resolves cases through settled agency actions approved by the Commission. Less frequently, cases are brought in federal court and either litigated to judgment or resolved with a consent order entered by the court. Although the Commission speaks as a whole through the language of the administrative order, Commissioners are free to publish their own views on the matter resolved.4 The publication of such separate statements has increased dramatically over the years covered in this article. In 2017, only 10 such statements were published.5 Moving forward eight years, in 2024, Commissioners published 103.6 That increase in activity provides a unique opportunity to understand the different views of the Commissioners and to potentially gain insight into the views that will be advanced by the majority party in the new administration.

Substantive Conclusions

Below are a handful of conclusions that are discernable for market participants attempting to anticipate what is likely to change and what is more likely to stay the same.

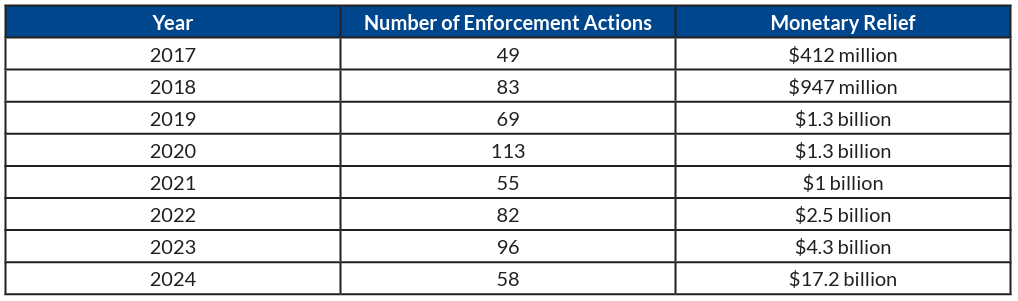

Although it may change focus, there is no reason to believe the DOE will be less active

Although the Trump administration has made broad statements that it intended to "dismantle Government Bureaucracy, slash excess regulations, cut wasteful expenditures and restructure Federal Agencies,"7 there is reason to doubt that such a policy will take the form of less activity by the CFTC Division of Enforcement. When comparing the Enforcement results of the first four years of the Trump administration to the four years under President Joe Biden, the CFTC brought, on average, seven more cases per year under the Trump administration than under the Biden administration. The following table sets forth the raw numbers.

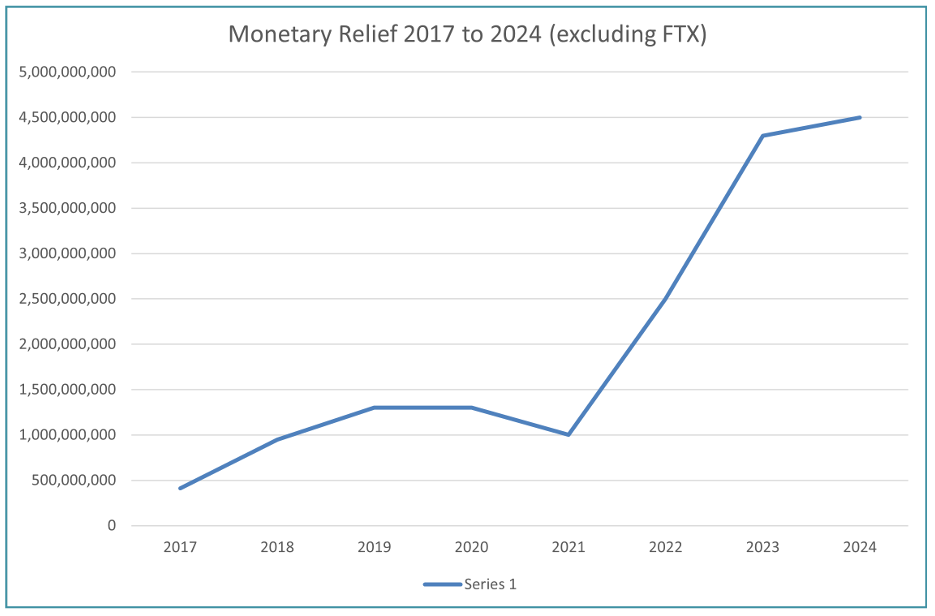

Notably, the 2024 results were largely driven by the FTX matter, which resulted in $12.7 billion in monetary relief. If the FTX matter is excluded, the monetary relief for 2023 would be $4.5 billion, which brings the total closer to the 2023 figures. Additionally, the level of monetary relief increased in size; however, that increase appears far more likely to be driven by a nearly unbroken rise in monetary relief for many years:

Although there are certainly reasons outside of the administration that explain the magnitude of fines and the number of cases under both administrations, it remains true that the DOE resolved fewer cases during the Biden administration than during the four years when Trump was first president. That observation is amplified by the fact that 27 of the 291, or more than 9 percent, of enforcement cases since 2021 have involved alleged violations related to the use of unapproved methods of communication.8

Although the government may attempt to relieve the regulatory burden on market participants in other ways, historical enforcement activity does not provide evidence that the DOE is likely to be less active.

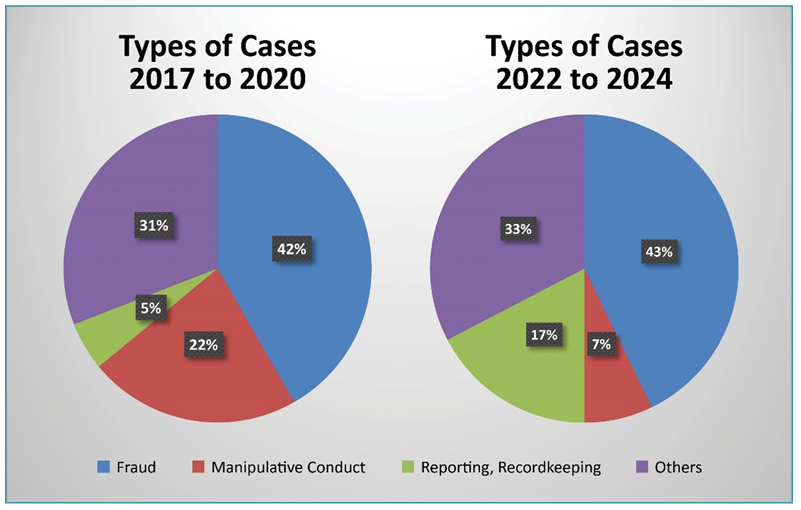

Enforcement activity could shift from reporting and recordkeeping to fraud and market abuse

A second potential observation supported by both the historical activity of the DOE and the statements of Commissioners is a shift in emphasis away from reporting and recordkeeping cases and a shift toward fraud and market abuse.

During the first Trump administration, the DOE made its priorities clear and articulated fraud and manipulation as significant areas of focus. Every Annual Review released during that time noted that the Commission prioritized "protecting customers in commodity and derivatives markets from fraud and other abuse."9 Of course, the Division has always described stopping fraud market abuse as a priority, and those categories, combined, make up the majority of the settled docket in both periods under review. Nonetheless, the following charts, which reflect the allocation of cases by subject matter, as identified by the DOE in its reporting of activity, make a sustained reallocation of priorities evident.

Under the first Trump administration, fraud and manipulative conduct made up 64 percent of the resolved cases, with reporting cases comprising only 5 percent. Under the Biden administration, those combined cases of fraud and manipulative conduct fell to 50 percent of total enforcement matters and reporting cases grew by 12 percent. There are, of course, explanations outside the DOE that are relevant. The Department of Justice actively pursued spoofing cases during the Trump period, a pattern of misconduct that has declined in recent years. The SEC led a sweep of financial firms relating to cases involving off-channel communications during the Biden period, joined by the CFTC, which resulted in 27 actions during the prior four years.

Commissioners' comments in the prior four years make clear that they support focusing DOE resources "on cases that will bring justice for victims, protect those that cannot protect themselves, and root out misconduct and wrongdoing — this is our core mission and core strength."10 As Commissioner Summer Mersinger stated in a Dissent from a case involving DeFi, "The decision to devote resources to this case also raises concerns about the Commission's enforcement priorities . . . For every case we bring against a DeFi protocol where there are no allegations of fraud or complaints of customers losing money, we risk taking resources from a case where innocent victims suffer actual financial harm at the hands of a real fraudster."11

A reversal in the increase in actions relating to data reporting, in particular, seems highly likely. These actions include, primarily, cases brought based on errors in swap data reporting, but also include recordkeeping requirements for introducing brokers.12 During the four years of Trump's first term, such actions were rare and a much smaller portion of the case activity. Of the 314 actions brought during the first Trump administration, only 16 (5.1 percent) involved reporting or recordkeeping violations. By contrast, under the Biden administration, of the 236 cases brought from 2021 to 2024, the Commission filed 41 cases (17.3 percent) involving reporting or recordkeeping violations.13

But even if the data on the increase in reporting and recordkeeping cases can be explained by the sweep related to off-channel communications, a reversion to the prior, lighter emphasis on enforcement cases for resolving reporting violations is also supported by the comments of Commissioners. Commissioner Caroline Pham has raised concerns regarding "the CFTC's aggressive enforcement posture towards pursuing reporting violations with a strict liability standard and no materiality threshold, resulting in seven-figure penalties for anything less than 100% perfection."14 That lack of tolerance for errors that underlie many of the data reporting cases came under particular scrutiny, with Commissioner Pham noting that, "It is fantastical for the Commission to expect perfection — 100% compliance for 100% of the time — when it comes to operations and technology systems and processes. That is impossible."15

In a case in which a registrant settled a matter relating to a failure to record certain phone calls based on a lapse during the COVID-19 pandemic by the vendor retained to manage those recordings,16 Commissioner Pham stated that the order and settlement reflected "the Commission's disturbing trend of 'examination by enforcement' — where the Division of Enforcement imposes a disproportionately high civil monetary penalty for one-off, non-material operational or technical issues with no misconduct, harm to clients, or financial losses, and that every other major regulatory authority addresses through an examination program conducted by supervisory staff (i.e., examiners)."17

Given the clear balance of resources focused on fraud and market misconduct cases in the first Trump administration and the expressions of frustration from sitting Commissioners regarding pursuing enforcement matters or issues that are better suited to resolution through the examination process, there is a strong possibility that enforcement priorities will be realigned away from data reporting cases in the second Trump administration.

Enforcement actions based on novel theories are likely to decline

Going forward, the Commission is likely to avoid enforcement matters perceived as applying new standards to historic conduct without the benefit of notice to the public prior to the change, so-called "regulation by enforcement." Several cases brought in the last two years that have been perceived by Commissioners as applying new standards without fair notice have been highlighted by dissenting statements.

For example, in her dissent on the Commission's off-channel communication enforcement action against Piper Sandler Hedging Services, LLC (Piper Sandler), Commissioner Mersinger emphasized that "regulation through enforcement is the antithesis of regulatory clarity and transparency."18 In that case, the CFTC charged Piper Sandler, an Introducing Broker, with failing to retain required records.19 Commissioner Mersinger criticized the DOE for failing to apply the particular record retention rules unique to introducing brokers, instead effectively taking the view that, "everything is a business record, even if such a conclusion has no foundation in the Commodity Exchange Act or CFTC regulations."20 Mersinger concluded: "I cannot support further settlements with IBs concerning offline communications violations until such time as the Commission as a whole, not just the Division of Enforcement, uses the actual words of the statute and the implementing regulation to clarify how an IB can properly comply with recordkeeping requirements."21

Commissioner Pham has expressed similar suspicions of the CFTC's use of "regulation by enforcement" and has even characterized the Commission's actions as going beyond regulation by enforcement and becoming increasingly pernicious. In CFTC v. Cartu (Masten et al.), the Commission charged Ryan Masten and Bareit Media LLC (Bareit Media) with violating the Commodity Exchange Act for failing to register as a commodity trading advisor (CTA).22 The parties' Consent Order noted that Bareit Media, which is controlled by Masten, offered customers the ability to obtain trade signals and automate trading on binary options platforms using those signals. In her dissent, Commissioner Pham admonished the CFTC for "once again changing its interpretation of the definition of a CTA in an enforcement action without sufficient explanation and without the opportunity for the public to comment."23 Commissioner Pham noted that for 10 years, the Commission stated that "a technology provider that aggregates (but does not originate) trade signals and submits orders to an exchange is not likely required to register as a CTA."24 Yet, the Commission arbitrarily changed its interpretation of the definition of a CTA to require technology providers that do not originate trade signals to register as CTAs, which Commissioner Pham claimed was "not merely regulation by enforcement."25

Going forward, the DOE's comments suggest that the Commission is less likely to support a foray into untested waters, bringing cases to establish standards or define conduct that was not clear from prior regulatory guidance. For many areas, notably cryptocurrencies, that limitation could be meaningful.

Cryptocurrency enforcement is likely to change

Likely changes in enforcement trends related to cryptocurrency are not necessarily dependent on the views of sitting Republican Commissioners and not illuminated by prior enforcement activity; instead, the strongest indication of the direction of cryptocurrency stems from the contrast between the Biden administration's actions and Trump administration's recent statements regarding cryptocurrency regulation.

It is certainly true that cryptocurrency cases are now a material part of the Enforcement docket, despite being virtually absent in the prior administration, as the number of cryptocurrency cases grew dramatically under the Biden administration. The CFTC under the Trump administration in 2020 brought just seven cryptocurrency cases; under the Biden administration, the number of cases increased to twenty in 2021, eighteen in 2022, and forty-seven in 2023. This increased attention towards cryptocurrency is not unique to the CFTC. For instance, under the Biden administration, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) issued "pause" letters to banks between March 2020 and May 2023, asking them to "pause, or not expand, planned or ongoing crypto-related activities and provide additional information."26 Meanwhile, the SEC has also seen a steady increase in cryptocurrency enforcement actions under Biden.27

In stark contrast, the Trump administration's campaign promised: it would be a "pro-crypto" administration; SEC Chairman Gary Gensler would be removed from his position to drive the SEC towards a friendlier stance with the cryptocurrency industry; cryptocurrency rules and regulations would be "written by people who love [the cryptocurrency] industry, not hate [the] industry"; the United States will create a strategic bitcoin reserve28; and America will become the "crypto capital of the world."29 Notably, during his first term, the Trump administration approached block chain and decentralized finance by fostering discussions of the new technologies in the LabCFTC and other forums.30

In the case of the SEC, the new administration clearly selected an individual who publicly supported the potential for innovation in that space. Prior to his nomination, Paul Atkins was a co-chair of Token Alliance, an industry-led initiative of the Chamber of Digital Commerce whose "mission is to promote the acceptance and use of digital assets and blockchain-based technologies,"31 and has attended various podcasts and other public appearances discussing his support for cryptocurrencies. President Trump toted Paul Atkins as a "proven leader" who "recognizes that digital assets & other innovations are crucial to Making America Greater than Ever Before."32

Such a focus on allowing "innovation" may decrease the efforts to use enforcement actions to shape the regulation of decentralized finance and blockchain matters. Some matters have been charged as straightforward registration failures, alleging that the activity allowed on the DeFi platform required registration as a futures commission merchant (FCM) or execution on a regulated platform. In CFTC v. Ooki DAO (formerly d/b/a bZeroX, LLC), the Commission obtained a default judgment against a decentralized autonomous organization ("DAO") for engaging in unlawful off-exchange leveraged and margined commodity transactions; engaging in activities that can only be performed by a registered futures commission merchant; and failing to implement know your customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) procedures.33 Following CFTC v. Ooki Dao, the CFTC has also imposed fines on three DeFi protocols for illegally offering leveraged and margined retail commodity transactions in digital assets, failing to register as a swap execution facility, failing to register as a designated contract maker, and/or failing to register as a futures commission merchant.34 In doing so, Director Ian McGinley of the DOE stressed that the DOE will "aggressively pursue those who operate unregistered platforms that allow U.S. persons to trade digital assets themselves." Notably, Commissioner Mersinger favored the application of the Commodity Exchange Act and CFTC rules to novel circumstances, but she dissented because the cases gave "no indication that customer funds have been misappropriated or that any market participants have been victimized by the DeFi protocols on which the Commission has unleashed its enforcement powers."35 Commissioner Mersinger again noted that the CFTC engages in regulation by enforcement rather than inviting the public to help solve novel DeFi issues.

Finally, in In re Universal Navigation Inc., the Commission settled charges against Universal Navigation Inc. d/b/a Uniswap Labs (Uniswap), finding that Uniswap "illegally offered leveraged or margined retail commodity transactions in digital assets via a decentralized digital asset trading protocol."36 The settlement order found that Uniswap provided users leveraged exposure to Ether and Bitcoin, which could be offered to non-Eligible Contract Participants only on a board of trade that was registered by the CFTC as a contract market because the leveraged tokens did not result in actual delivery within 28 days. Commissioner Mersinger dissented and stated the case has "all the hallmarks" of regulation through enforcement: "A settlement with a de minimis penalty that bears little relationship to the conduct alleged, sweeping statements about the broader industry that are not germane to the case at hand, and legal theories that have not been tested in court."37 Commissioner Pham echoed this sentiment, arguing that the Commission's actions violated the Administrative Procedure Act and noting the CFTC's approach was "legally simplistic and conveniently cuts corners to create a pretext for enforcement."38 If the newly constituted Commission focuses on fostering innovation, relying on the rulemaking process instead of enforcement actions to provide guidance on unsettled matters, and shifts its emphasis to the examination process from the enforcement process, such controversial extensions of jurisdiction may take a different form going forward. Accordingly, we anticipate that future enforcement actions involving cryptocurrency may be limited to fraud or manipulation cases.

Conclusion

Obviously, many factors will determine the shape of the DOE agenda, most of which are difficult to predict. Nonetheless, to the extent the sources identified herein provide some guidance, market participants can expect a DOE that continues a robust docket and seeks significant fines but focuses more on core matters of protecting investors from fraud and non-technical misconduct.

/>i

/>i