Bankruptcy is a term that tends to instill images of “For Sale” or “Everything Must Go” signs posted in windows, but this often is not the case. In fact, a bankruptcy filing is one way for a business to refocus its efforts and reorganize.

Indeed, throughout history, many Fortune 500 companies have at some point filed for bankruptcy, successfully reorganized and prospered. For this reason, a good bankruptcy lawyer approaches the process as a surgeon with a scalpel (rather than a sledge hammer). A company that files Chapter 11 bankruptcy will, in most cases, be a “debtor-in-possession,” and its management and board will retain control of the company so it can continue to conduct business during the pendency of its reorganization. In order to assist employers in understanding some of the bankruptcy nuances, we have prepared this alert identifying some of the most important employment and employee benefit issues in US bankruptcy cases.

The Automatic Stay

Bankruptcy affords distressed companies many types of relief, but none is more immediate and profound than the automatic stay. One of the principal purposes of bankruptcy is to allow a debtor to have a breathing spell – a respite from creditor pressure – so that it can assess its strengths and weaknesses, take stock of all obligations and develop a plan to pay creditors while moving forward as a restructured company (or perhaps sell its assets and wind down). The automatic stay is effectively a broad, nationwide injunction triggered immediately upon the filing of a bankruptcy petition that stops almost all actions and proceedings against a debtor or its assets. This includes employment-related and other litigations, foreclosures, collection actions, enforcement of judgments and actions to perfect liens granted before the bankruptcy was filed.

Critically, the automatic stay will only enjoin actions against the debtor on the basis of its pre-bankruptcy actions. For example, a plaintiff in a wrongful termination action will have to pause its litigation against its debtor’s former employer, and their claim will become a general unsecured claim in the bankruptcy that would be paid pro rata with other unsecured creditors. If, however, the debtor wrongfully terminates an employee after the filing of the bankruptcy petition, the automatic stay will not prevent that employee from suing the debtor for its post-bankruptcy conduct.

First Day Employee Wage and Benefits Motion

While a company that files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy has the ability to remain “in possession” of its operations, the Bankruptcy Code imposes many restrictions, which, if not addressed, will hamper business operations. Typically, a debtor files a series of first-day motions, which will ask for immediate temporary relief to allow operations to continue. Examples of such requests include asking for court approval to (1) continue using existing cash management systems, (2) continue customer programs, (3) continue using existing insurance and (4) address payment of pre-bankruptcy employee wages and benefits.

Specifically, any pre-bankruptcy wages and benefits that employees have earned but for which they have not been paid are claims against the estate, which ordinarily would require each employee to file a proof of claim and await administration of the bankruptcy prior to receiving payment. This delay would substantially disrupt operations within the company – employees who are not paid may not come to work, hampering the reorganization effort. Recognizing the importance of paying employees, the Bankruptcy Code gives payment priority to employee wages earned in the 180 days prior to the case being filed, capped at US$13,650 per employee. Because employees have this priority right to payment and because paying employees is integral to maintaining its workforce, a debtor will file a first-day motion asking for court approval to pay in the ordinary course prebankruptcy employee wages and benefits up to US$13,650. Courts regularly approve this motion, sometimes even for amounts exceeding the statutory cap, if the debtor can make a compelling case. The first-day wage and benefits motion is critical to a debtor’s soft landing and smooth transition into bankruptcy.

Key Employee Incentive and Retention Plans

Bankruptcy is necessarily disruptive to a company’s operations and often results in substantial uncertainty; accordingly, companies in Chapter 11 often experience trouble retaining essential employees and top management. To prevent attrition at the most critical levels, debtors may seek to implement key employee retention plans (KERPs) and/ or key employee incentive plans (KEIPs). There was a time when courts would approve a KERP – enhanced payment for simply sticking with company – by deferring to the business judgment of the debtor. This was a relatively low standard of review, which resulted in a perception of abuse. Ultimately, this perception led to stricter standards.

Section 503(c) of the Bankruptcy Code was enacted to “stop the travesty of high-level corporate insiders who walk away with millions while the company’s workers and retirees are left empty-handed.” Section 503(c) restricts retention or severance payments to insiders, which are intended solely to induce them to remain with the debtor. It also prohibits any such payments to insiders and others that are outside the ordinary course of business and not justified by the facts and circumstances of the Chapter 11 case. Under this stricter standard, KERPs are more difficult to justify, and it is even questionable whether long-standing pre-bankruptcy KERPs will be honored in bankruptcy, if they are primarily retentive in nature.

The introduction of 503(c) and the limits on KERPs have given way to a preference for KEIPs. Rather than retentive in nature, KEIPs are designed to reward an employee for performance. For a KEIP to withstand scrutiny, it must be viewed as a payment for value, rather than a payment to simply stay with the debtor. Any KEIP seeking to side-step section 503(c) requirements must establish performance goals such as successfully reorganizing the company, meeting sales targets, etc. KERP/KEIP analysis in the bankruptcy setting requires detailed considerations beyond the scope of this article, and a company considering bankruptcy should raise these issues with their restructuring counsel prior to filing a bankruptcy petition.

Rejection of Employment Agreements

In addition to the automatic stay, another significant benefit of Chapter 11 is that it allows a debtor to assume or reject its existing executory contracts. Executory contracts are those where performance obligations remain for both parties such that failure to perform would be deemed a breach. During bankruptcy, the debtor is entitled to use its business judgment to decide whether to assume or reject any executory contracts to which it is a party. Provisions in those agreements purporting to prohibit or restrict such rejection are unenforceable.

If an executory contract is assumed, it reaffirms the debtor’s decision to continue with that agreement, and the debtor must cure all existing defaults. If an executory contract is rejected, the agreement is not terminated, but it constitutes a breach by the debtor, which will relieve the non-debtor party from performance, and any damage claim that arises from that breach is treated as a pre-petition general unsecured claim. A contract must be assumed or rejected as a whole (i.e., it is all or nothing). Note that, generally, the deadline to make the decision to assume or reject executory contracts is made toward the end of the bankruptcy case. Pending that decision, the parties to executory contracts are generally obligated to perform under the contract.

Employment agreements are often executory contracts subject to assumption or rejection by a debtor. Typically, employment agreements are not assumed during the pendency of a bankruptcy case because it is uncertain how a case will resolve, and a debtor will not know if it wants to keep on any particular employee (e.g., there may be changes in management).

However, it is not uncommon for a debtor to terminate an employee that is subject to an employment agreement. In that circumstance, the debtor will seek to reject the employment agreement, which ordinarily will give rise to claims for breach by the terminated employee. Employment agreements are not the only executory contracts impacting the debtor’s employment operation. Contracts for payroll services, outside human resource management, and even collective bargaining agreements, are also executory contracts that may be assumed or rejected.

Rejection of Collective Bargaining Agreements

Among a debtor’s contract rejection powers is the ability to seek to reject collective bargaining agreements (CBA). This is a uniquely powerful tool that can allow a debtor to renegotiate and restructure substantial legacy costs. In order to reject a CBA, section 1113 of the Bankruptcy Code requires the debtor to present the authorized representative of the bargaining unit with a proposal containing what the debtor believes are the necessary modifications to the CBA to ensure that all affected parties (e.g., debtor, creditors and employees) are treated fairly and equitably. The debtor must also give the bargaining unit all necessary information to assess the proposed modifications. Then, the debtor and the bargaining unit must engage in good faith negotiations for a reasonable period. If no deal is reached, the court can approve the CBA rejection so long as (a) the debtor has fulfilled the various requirements set forth above; (b) the court determines the bargaining unit has rejected the proposal without good cause; and (c) the balance of the equities favors rejecting the CBA.

Note that even if a CBA is rejected, the debtor is not relieved of its duty to meet and bargain with the union – the union remains the representative of the employees.

Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (Warn) Notices

The federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act (WARN) requires covered employers to give 60 days’ advance written notice of certain plant closings or mass layoffs to affected employees. Covered employers for WARN purposes are those with 100 or more full-time employees. Notice is generally required when 50 or more full-time employees experience an employment loss due to a plant closing or mass layoff. Some states have their own versions of WARN laws as well.

If WARN compliance is not top of mind for a distressed company as it is managing to a possible bankruptcy filing, it needs to be. It is critical to address these issues, as remedies for failure to provide timely WARN notice includes back pay for the period of the violation plus penalties and attorneys’ fees. Post-petition WARN violations are at risk of being treated as administrative claims while pre-petition violations have the same priority as other wage claims.

There are provisions in the WARN statute allowing the employer to shorten the 60-day notice requirement but, importantly, not to be excused entirely from providing notice.

The faltering company exception applies to a “plant closing” (but not merely a “mass layoff”) where, at the time notice would have been required, the employer was actively seeking capital or business, which, if obtained, would have enabled the employer to avoid or postpone the shutdown and the employer reasonably and in good faith believed that giving the required notice would have prevented the employer from obtaining the needed capital or business.

The natural disaster exception applies when employment losses triggering notice are the direct result of natural disasters (e.g., floods, earthquakes, storms, droughts and similar effects of nature).

The unforeseeable business circumstances exception (which is the one that will likely be relied upon the most during the COVID-19 pandemic) applies if the closing or mass layoff is caused by business circumstances that were not reasonably foreseeable as of the time that notice would have been required. “Reasonably foreseeable” means probable, not just possible, which means an employer should constantly reassess whether this exception applies. Unforeseeable business circumstances include an unanticipated and dramatic major economic downturn or non-natural disaster, as well as a “government ordered closing of an employment site that occurs without prior notice.”

Importantly, however, even if one of the WARN exceptions applies, the employer is still required to give as much as notice as is practicable and at that time must give a brief statement of the basis for reducing the notification period. Distressed companies need to be aware of and monitor their notice responsibilities under WARN (and state WARN laws if applicable) early on and continually reassess whether (and how much) notice is needed throughout the bankruptcy process.

Employee Benefit – Controlled Group Rules

One of the more important concepts regarding employee benefits is the controlled group rules. Both the Internal Revenue Code (Code) and the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) aggregate different entities that are part of a “controlled group” for purposes of determining both overall compliance and liabilities related to various employee benefit rules. The following is a sample of various employee benefits rules that are impacted by the controlled group rules:

-

Controlled group members are jointly and severally liable for pension plan obligations, such as single employer pension plan liabilities, multi-employer pension plan liabilities (such as withdrawal liability) and pension plan termination premiums.

-

Obligations to offer continuation coverage under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA).

-

The requirement to offer affordable healthcare coverage under the Affordable Care Act’s employer mandate tax.

Prior to commencing a bankruptcy case, it is important to identify all members of the controlled group and their potential employee benefit plan implications. In other words, it might be important to be certain that all entities that are jointly and severally liable in a controlled group file for bankruptcy protection at the same time. There are generally two types of controlled groups – a parent-subsidiary controlled group or a brother-sister controlled group.1

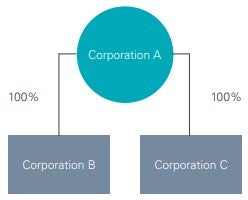

A parent-subsidiary controlled group exists when a parent company owns (directly or indirectly) at least 80% of another entity. Below is an example of a parent-subsidiary controlled group with Corporations A, B and C.

The second type of controlled group is a brother-sister controlled group, which is a bit more complicated than the parent-subsidiary controlled group. In the general sense, a brother-sister controlled group exists if both (1) the same five or fewer people own 80% of one entity and (2) the same five or fewer people together own more than 50% of another entity taking into account the ownership of each person only to the extent such ownership is identical with respect to each organization. The following is an example of the brother-sister controlled group analysis from the IRS:

Example: Adams Corp and Bell Corp are owned by four shareholders, in the following percentages:

| Shareholder | Adams Corp | Bell Corp |

|---|---|---|

| A | 80% | 20% |

| B | 10% | 50% |

| C | 5% | 15% |

| D | 5% | 15% |

| Total | 100% | 100% |

In this example, the first test is met because the shareholders own 100% of the stock; however, a brother-sister controlled group does not exist because the second test is not met as shown by the following percentages:

| Shareholder | Identical Ownership Percentage in Both Corps. |

|---|---|

| A | 20% |

| B | 10% |

| C | 5% |

| D | 5% |

| Total | 40% |

When applying these rules, the Treasury Regulations provide certain ownership attribution rules. The application of the ownership attribution rules can result in a brother-sister controlled group if the ownership interest is deemed held by another.

Pension Plan Liabilities

One of the many considerations to take into account in a bankruptcy is how to handle pension plan liabilities. Prior to the introduction of 401(k) plans in the 1980s, many employers offered retirement benefits in the form of defined benefit pension plans. These pension plans can have significant underfunded liabilities. In addition, some pension plans were part of good faith negotiations between an employer and a union.

Similar to other employee issues discussed above, the automatic stay comes into play with respect to pension plan liabilities. As a reminder, the automatic stay applies to the debtor that filed and it would generally not apply to the pension plan and its underlying trust – this is because the pension plan and trust are separate legal entities and are not debtors. However, it is often the case that a debtor is a plan sponsor or a participating employer. The automatic stay would not prevent a claim for benefits under the pension plan and underlying trust; however, the automatic stay could provide protection from the debtor being subject to Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) liens and IRS funding deficiency excise taxes. Accordingly, it is important to identify the roles that a debtor may play with respect to a pension plan and to identify any outstanding pension plan liabilities prior to filing the bankruptcy.

Asset Purchase Agreements/Stock Purchase Agreement Considerations

A Chapter 11 debtor may seek to sell some or all of its assets. In most cases, this sale will take the form of an asset sale, such as a sale of a plant or facility. In rare cases, the sale will take the form of a stock/equity sale of the entity.

Similar to the non-bankruptcy setting, an asset sale ordinarily involves the termination of the employment relationship between the asset seller and the individuals employed at the plant/facility followed by the possible immediate employment of those individuals by the asset buyer. In that situation, the parties must be aware of what employee-related obligations are triggered, such as severance, payment of accrued vacation/paid time off, and obligation to offer COBRA coverage. In contrast, the employment relationship usually is not terminated in the case of a stock/equity sale. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind the structure of the sale.

Role of Unsecured Creditors Committee

This article discusses high-level employment issues in bankruptcy, but it is essential to understand that a debtor’s administration of its case is subject to oversight from various constituencies, such as the Office of the US Trustee, financial stakeholders and the statutory committee of unsecured creditors (the Committee). The Committee is established at the outset of the case and is composed of a group of unsecured creditors who serve in a fiduciary capacity for the benefit of all unsecured creditors. In a Chapter 11 case, as long as there are creditors willing to serve on the committee, a committee will be usually be formed. The Committee allows unsecured creditors to have a voice in a debtor’s case and influence the outcome, while ensuring that the interests of unsecured creditors are protected. It has standing to be heard in court on any issue and it has broad powers, which make it an effective watchdog and relevant constituent in the case. The Committee is permitted to hire professionals (including counsel) at the debtor’s expense.

A successful Chapter 11 case typically requires a debtor to build consensus among its various constituent groups. To accomplish this, regular consultation with the Committee is essential. For example, a proactive debtor might request Committee input before seeking court approval of a KERP or KEIP so that the debtor can negotiate terms and perhaps avoid an objection. Managing its stakeholder and various constituent groups requires a debtor to play a game chess, and it is through this lens it should analyze its options and strategy, including those impacting employment issues.

1 Note – In addition to controlled groups, entities may be required to be aggregated if they constitute an “affiliated service group.” An affiliated service group exists where certain common ownership interests exist between two entities and employees of those entities perform services for the other entity.

/>i

/>i