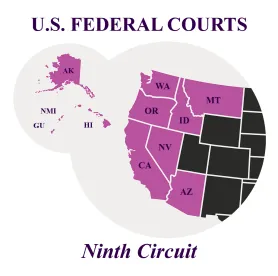

In reversing a Nevada district court’s grant of summary judgment, the Ninth Circuit, in Cadena v. Customer Connexx LLC, recently held that the time call center employees spent booting up their computers is compensable. Because a functioning computer was necessary for the call center employees to do their job, the court unanimously agreed that the time required to turn on their computer and log in was “integral and indispensable to their principal activities” and, therefore, compensable, subject to certain limitations.

So, What Happened?

The plaintiffs in Cadena were hourly, non-exempt call center agents whose primary job duty was to provide customer service and scheduling functions for customers using a computer-based phone program. In order to connect their phone and start accepting calls, agents were required to turn on or wake up their computers, log in using their credentials, and open the timekeeping system, which they alleged took anywhere from 6 to 20 minutes. The plaintiffs further alleged that at the end of their shift, call center agents were required to spend an approximate average of 4 to 8 minutes wrapping up calls, closing out of computer programs, clocking out, and logging or shutting down their computers.

In the lawsuit, the plaintiffs asserted claims under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and Nevada law contending that they should have been, and were not, paid for the time spent booting up their computers prior to clocking in or closing down their computers after clocking out. The district court granted summary judgment for Connexx, reasoning that Connexx had hired the employees to answer customer phone calls and perform scheduling tasks, and not to start and shut down computers. Therefore, the district court held, the starting and shutting down of computers were not principal activities. The district court also concluded that those tasks were not “integral and indispensable” to the employees’ duties as call center customer service agents. The Ninth Circuit reversed.

Integral and Indispensable Activity

By way of background, the Portal-to-Portal Act of 1947 relieves employers of the obligation to pay employees under the FLSA for activities performed “preliminary to or postliminary to” any principal activities for which they are employed. Since the Portal-to-Portal Act amendments to the FLSA, a series of Supreme Court rulings have further defined the distinguishing line between compensable principal activities and non-compensable preliminary and postliminary tasks:

-

Steiner v. Mitchell, 350 U.S. 247, 256 (1956): Held that “activities performed either before or after the regular work shift . . . are compensable . . . if those activities are an integral and indispensable part of the principal activities for which covered workmen are employed.”

-

IBP, Inc. v. Alvarez, 546 U.S. 21, 37 (2005): Held that activities that are “integral and indispensable” are themselves treated as “principal activities” under the Portal-to-Portal Act. In addition, the first principal activity of the day begins the workday, and any waiting time that occurs between the first and last principal activity is compensable.

-

Integrity Staffing Sols., Inc. v. Busk, 574 U.S. 27, 36 (2014): Further clarified that “integral and indispensable” activities are those that (i) are an intrinsic element of the principal activities the employee was hired to perform, and (ii) tasks that the employee cannot dispense with in order to perform his or her principal activities.

The Ninth Circuit’s Take on “Integral and Indispensable”

In Cadena, there was no dispute as to whether the call center employees’ work answering customer phone calls and performing scheduling tasks were principal activities. The Ninth Circuit disagreed with the district court’s conclusion—i.e., that Connexx did not hire customer service agents to turn computers on and off or to log in and out of a timekeeping system, and therefore, those tasks were not compensable principal activities—criticizing the district court as having oversimplified the inquiry. The real question at issue, the Ninth Circuit reasoned, was whether engaging the computer, which contains the phone program, customer information, and email programs, is integral to the employees’ duties. The court concluded that it was: because the employees’ duties could not be performed without turning on and booting up their work computers, those boot-up activities were integral and indispensable from their principal duties and compensable.

But Wait, There Are Limitations

In rendering its decision, the Ninth Circuit limited the scope and applicability of its holding. First, the court limited its decision to the facts of the Cadena case and refused to consider whether the same time would be compensable if the employees worked remotely or used their personal computers to perform their duties. In other words, in the Ninth Circuit, the time spent booting up a computer is arguably compensable, at least for now, only for employees “using employer-provided computers to perform their duties while working at a central work site.”

The court also declined to consider whether the time spent shutting down a computer is compensable. Explaining that shutting down a computer is not integral and indispensable to the employees’ ability to make calls, the Ninth Circuit remanded the issue to the district court to determine whether the time spent shutting down the computers was a principal activity in and of itself, such that it would be compensable.

Additionally, Connexx asked the Ninth Circuit to affirm the summary judgment on the basis that even if the boot up time was not preliminary, it is not compensable under the de minimis doctrine. Since the district court did not reach this issue, the court remanded the question to the district court without opining on the issue.

Impact and Takeaways

This is not the first time the Ninth Circuit has addressed this issue, nor is the Ninth Circuit the first federal appellate court to do so. The Tenth Circuit, in Peterson v. Nelnet Diversified Solutions, LLC, decided a similar case and concluded that the time call center representatives spent logging into their computer was compensable. The Tenth Circuit also considered the de minimis doctrine and held that the doctrine did not apply to the facts in that case because “the regularity and absence of administrative difficulty in recording the time made it compensable.” These courts reached different conclusions in other cases. For example, in Rutti v. Lojack Corp., the Ninth Circuit held that logging into a handheld device that notified the employee of his jobs for the day, along with other pre-shift activities, was not integral to a car alarm installer’s duties. The Tenth Circuit similarly ruled in Jimenez v. Board of County Commissioners of Hidalgo County that a 911 dispatcher’s pre-shift activities of putting on a headset and logging into a computer were preliminary, non-compensable tasks.

Employers should keep Cadena and similar rulings addressing the compensability of pre- and post-shift tasks in mind when considering whether to compensate employees for certain activities.

Alexandria Adkins also contributed to this article.

/>i

/>i