Introduction

We have set out below an overview of the current regulatory frameworks governing Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) in the key jurisdictions of the UK, EU and USA.

SAF has emerged as a critical component in the global drive to decarbonise the aviation sector, a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Unlike conventional jet fuels, SAF offers substantial reductions in lifecycle carbon emissions by incorporating renewable feedstocks and innovative production technologies.

Recognising its potential to drive sustainable growth, policymakers across the UK, EU, and USA are actively shaping regulatory frameworks to accelerate its deployment and adoption.

Note that this is an evolving regulatory landscape that is subject to change – however, this overview sets out the current regulations and initiatives of each of the UK, EU and USA – and strongly indicates the direction of travel of each of these jurisdictions.

We conclude with a comparison of these jurisdictions and analyse their strengths and limitations in fostering market growth. We also examine potential pathways for future development, including harmonisation of international standards, technological advancements, and policy synergies.

By presenting such analysis and exploring projected trends, this overview offers insights into the role of regulation in shaping the trajectory of SAF as an essential enabler of sustainable aviation.

United Kingdom

The UK SAF landscape

Current Status and Future Developments

The UK’s SAF industry is progressing rapidly, driven by a number of policy measures that integrate SAF into the UK’s broader decarbonisation goals. With increasing regulatory and financial support, the UK aims to position itself as a global leader in SAF development, production, commercialisation and use.

A key component of this strategy is the SAF Mandate, alongside other legislative and market-based incentives designed to accelerate SAF adoption. Under these principles, SAF is defined based on achieving a minimum level of greenhouse gas emission reductions and specific sustainability criteria.

The key features include the introduction of compulsory, incrementally increasing SAF supply requirements, a buy-out mechanism to enforce compliance, and funding incentives to support industry growth.

The Jet Zero Taskforce (JZT) (building on the previous Government’s Jet Zero Council) was announced by the UK Government in November 2024 to advance sustainable aviation. Members include UK Government ministers, industry leaders and academics. Established to accelerate the transition to net zero aviation by 2050, the JZT aims to streamline aviation decarbonization priorities and support the development, production, commercialisation and use of SAF in the UK and globally.

Legislation

The UK is at the forefront of SAF development as the one of the first countries in the world to legislate for mandatory SAF requirements. The UK’s key policy to decarbonize aviation and secure demand for SAF is the SAF Mandate.

- SAF Mandate

Key terms (2025 onwards):

- The Renewable Transport Fuel Obligations (Sustainable Aviation Fuel) Order 2024 came into force on January 1, 2025. This introduced compulsory SAF requirements for suppliers of at least 15.9 terajoules (c.468,000 litres) per year of aviation fuel to the UK: from 2025, SAF is required to make up 2% of the total UK aviation fuel mix, increasing to 10% by 2030 and 22% by 2040.

- SAF suppliers earn Renewable Transport Fuel Certificates for SAF supplied to the UK that meets certain GHG emission reductions and sustainability criteria (SAF must comprise fuel that achieves minimum GHG emission reductions of 40% relative to traditional fossil fuel-based jet fuel). Evidence of the SAF supplied to UK needs to be provided to the Department for Transport to assess and award corresponding certificates. The number of certificates issued will be proportionate to the level of GHG emission reductions achieved by the fuel delivered (i.e. the greater the reductions, the greater the number of certificates issued). Suppliers can either use their certificates to demonstrate that they have complied with their obligations or trade them to other suppliers.

HEFA Caps (2027 onwards):

- SAF produced through hydro-processed esters and fatty acids (HEFA) can contribute 100% of SAF for the first 2 years of the Mandate and thereafter decreasing to 71% in 2030 and 35% in 2040.

- This is due primarily to HEFA’s emission reduction inefficiencies (when compared to SAF alternatives) and feedstock sustainability concerns.

Power to Liquid (PtL) Obligations (2028-2040):

- A separate PtL obligation requires 0.2% of UK aviation fuel to be sourced from PtL commencing in 2028 and thereafter rising to 4.4% by 2040.

- PtL requires energy-derived production of aviation fuels (from e.g. green hydrogen and captured carbon dioxide).

Buy-out Mechanism (2025 onwards):

- Fuel suppliers unable to meet their SAF Mandate requirements must pay a buy-out price determined by their SAF or PtL shortfall amounts.

- The aim is to create a financial incentive to prioritize SAF, with the buy-out prices (currently £4.70 per litre for SAF and £5.00 per litre for PtL) being set at a level to encourage the supply of SAF over the use of the buy-out.

- SAF Revenue Support

The Sustainable Aviation Fuel (Revenue Support Mechanism) Bill (2024) was announced in the King’s speech on 17 July 2024, proposing a revenue certainty mechanism for SAF producers investing in UK-based facilities. A number of funding options were proposed and, in January 2025, the UK Government confirmed that the Guaranteed Strike Price mechanism was the preferred option.

- The Guaranteed Strike Price is envisaged to operate akin to a contract-for-difference (as utilised in the UK renewable power sector), offering price stability for UK SAF producers. The mechanism will operate through a private law contract between a UK SAF producer and a designated Government agency, establishing a strike price (being the guaranteed price the producer will receive for eligible SAF over a specified period). If the reference price surpasses the strike price, the producer reimburses the Government agency for the difference, and, if the reference price falls below the strike price, the Government agency compensates the producer for the shortfall.

- In line with the “polluter pays” principle, the UK Government has confirmed that it intends for the revenue certainty mechanism to be funded by aviation fuel suppliers.

Further SAF Incentives

To further promote UK SAF development, the UK Government has implemented various financial incentives:

- Advanced Fuels Fund: First launched in 2022 with £165 million of grant funding available, the Advanced Fuels Fund aims to support the establishment and development of first-of-a-kind SAF projects in the UK.

- SAF Clearing House: Any new aviation fuel must meet strict specifications and undergo testing to meet industry standards; the cost and complexity of which can be a significant barrier to new fuels entering the market. The UK SAF Clearing House provides technical support and funding to SAF producers.

- Furthermore, aircraft operators can reduce their obligations under the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) by using eligible SAF, which qualifies for emissions reductions under the scheme.

Projections and Insight

It is estimated that, by 2050, the global aviation industry will need approximately 400 million tonnes of SAF annually to meet international decarbonization goal and, whilst the SAF market is still in a nascent stage of its development, the UK is positioned to play a significant role in the global effort to decarbonize aviation. The development of SAF production facilities in the UK are key for the successful implementation of the UK Government’s SAF goals.

The SAF Mandate has only just come into force and the revenue certainty mechanism for SAF producers has yet to be finalized and take effect. As such it remains to be seen whether these mechanisms will be sufficient to meet international decarbonization goals and position the UK as a leader in SAF development, production, commercialisation and use:

- The success of the buy-out mechanism in incentivizing the production and use of SAF will depend on the future production costs of SAF. Whilst the buyout rates are currently projected to exceed SAF production costs, if the buy-out price is set too low (for example, if production costs spiral), suppliers may choose to simply pay the buy- out price.

- With respect to the revenue certainty mechanism, there are a number of questions and policy decisions that remain outstanding: what will be used as the “reference price” (unlike in the power market where there is a published market price for electricity, no such benchmark exists for SAF)? How will the strike price adjust over time? Precisely how will the mechanism be funded? At a most fundamental level, the deployment of significant capital into SAF development will require further clarity regarding the revenue certainty mechanism.

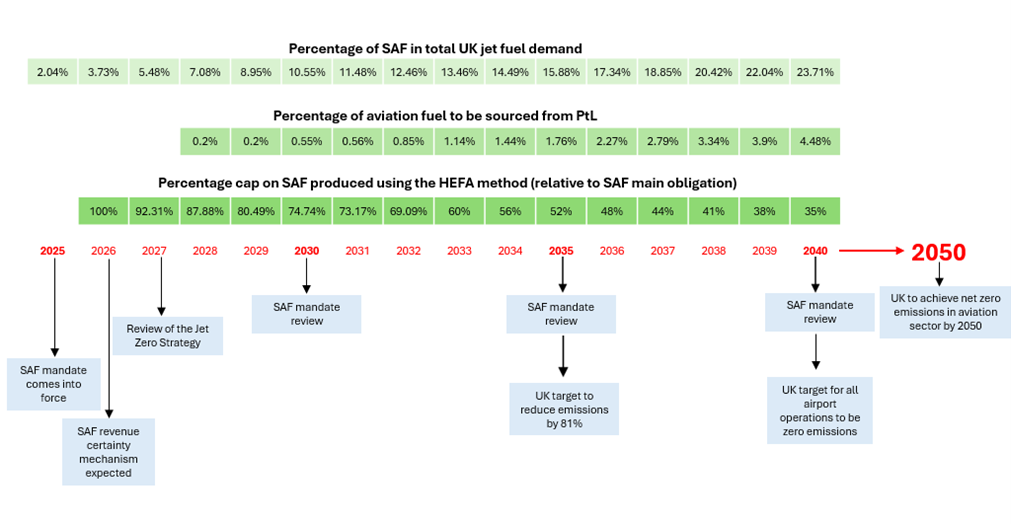

For further clarity on the information above, we set out below (at Figure 1) a timeline of key projected regulatory developments in the UK SAF market.

UK SAF Timeline

Figure 1: UK SAF Timeline

European Union

The EU SAF Landscape

Current Status and Future Developments

Despite efforts to curb its growth, commercial flights in the EU could rise by up to 42% by 2040 compared to 2017. Recognizing the pressing need to address the climate impact of the aviation sector, the EU has prioritized the development of a SAF market. By leveraging the collective action potential of its member states, the EU is uniquely positioned to lead in SAF implementation.

SAF is defined by the EU as a “drop-in” aviation fuel, including advanced biofuels or biofuels produced from sustainable feedstocks, recycled carbon fuels, or synthetic fuels.

With mandates introduced in 2023 and effective as from January 2025, the European Union is meticulously crafting a policy framework to stabilize the SAF market, foster innovation, and create a level playing field, driving progress toward its Fit-to-55 climate goals.

Legislation

The European regulatory framework for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) has been shaped by two key legislative milestones: the Renewable Energy Directives (RED) and the ReFuelEU Aviation Regulation.

The RED have progressively established binding renewable energy targets across the EU, including for the transport sector, and have increasingly integrated SAF into the broader energy transition strategy. From RED I (2009), which set initial renewable energy targets, to RED II (2018), which introduced incentives for SAF, and finally RED III (2023), which reinforced sector-specific mandates, these directives have paved the way for SAF regulation.

Complementing this framework, the ReFuelEU Aviation Regulation, adopted in 2023, marks a decisive shift in SAF development by imposing direct obligations on fuel suppliers at EU airports. Unlike the RED directives, this regulation is immediately applicable across the EU and imposes a progressive incorporation of SAF into jet fuel, with binding quotas extending to 2050. Together, these two instruments define the roadmap for SAF deployment, balancing long-term policy incentives with immediate regulatory requirements.

- RED Directives

RED served as the cornerstone for establishing the EU’s shift toward greener fuels.

Adopted on April 23, 2009, the RED I Directive introduced ambitious renewable energy targets across EU Member States:

- General Targets: Each Member State was assigned a binding target to achieve 20% renewable energy in its final energy consumption by 2020. These targets varied for each country: Some countries were optimistic about their renewable energy potential and set ambitious targets, such as Sweden with 49% by 2020, Denmark with 30%, and France with 23%. Others, however, were more cautious, with the Netherlands setting a target of 14% and Italy aiming for 17%.

- Transport Sector: A specific target of 10% renewable energy was set for the transport sector by 2020. This included biofuels and other renewable fuels but did not explicitly address aviation.

- Impact on SAF: While RED I did not explicitly include SAF, it established a foundation for their future integration by defining sustainability criteria and promoting advanced biofuels.

Entering into force on December 11, 2018, the RED II Directive strengthened the EU’s renewable energy framework in response to increased climate ambitions:

- Revised Targets: The overall binding target for emissions reduction was raised to 32%, with a renewable energy target of 14% for the transport sector.

- Promotion of SAF

- Advanced Biofuels and RFNBOs: The RED II Directive encouraged the use of advanced biofuels and Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin (RFNBOs), explicitly including SAF. Advanced biofuels refer to biofuels produced from feedstocks that do not compete with food production or contribute to land-use changes that could negatively impact biodiversity. They are typically derived from waste and residues, or non-food crops such as algae and plant fibers. As for RFNBOs, they are fuels produced from renewable electricity rather than biological sources.

- Incentive Multipliers

- Biofuels derived from feedstocks listed in Annex IX (including advanced biofuels) count twice their energy content towards renewable targets, meaning that for every unit of energy produced from these fuels, it counts as two units towards the target.

- Fuels supplied to the aviation sector (including RFNBOs) count as 1.2 times their energy content, meaning that for every unit of energy from these fuels, it counts as 1.2 units toward the target.

- Limitations on Food-Based Biofuels: These are capped at 7% to mitigate adverse effects on land use and food production.

Adopted on October 18, 2023, the RED III Directive was a decisive step towards integrating SAF into the EU’s energy framework, by:

- Enhanced Targets: The share of renewable energy in the EU’s overall energy consumption must reach 42.5% by 2030, with a binding target of 29% for the transport sector.

- Sectoral Sub-Targets: Specific targets were introduced for advanced biofuels and RFNBOs, solidifying SAF’s role as a cornerstone of aviation decarbonization.

- Aviation Catalyst: RED III emphasized increased SAF integration into national energy strategies while supporting emerging technologies, such as synthetic fuels.

Directives are legal acts that generally need be transposed into national law by EU member states, meaning that each country must adopt its own legislation to achieve the directive’s objectives. Therefore, the RED directives’ provisions need to be transposed into national law. There is generally an 18-month deadline for member states to do so, with an occasionally shorter deadline for some provisions.

Member States successfully met the RED I targets, despite varying national goals, demonstrating the EU’s commitment to renewable energy. This progress laid the foundation for the more ambitious targets in RED II and RED III, and Member States are on track to achieve these goals. In particular, the push for SAF under these directives is progressing well, with ongoing efforts to scale production and expand infrastructure. While challenges remain, Member States are well- positioned to meet the targets for both renewable energy and SAF by 2030, especially with the introduction of the ReFuelEU Aviation Regulation.

- ReFuelEU Aviation regulation

Regulation (EU) 2023/2405 of October 18, 2023 through ensuring a level playing field for sustainable air transport (ReFuelEU Aviation) represents a cornerstone of the EU’s strategy to decarbonize aviation in line with the Green Deal objectives and the Fit-for-55 package. This regulation establishes a comprehensive legal framework to accelerate the adoption of SAF across the EU.

Finalized in 2023, most of its provisions entered into force on 1 January 2024, with Articles 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10 becoming applicable from January 1, 2025. As an EU regulation, ReFuelEU Aviation is directly applicable in all Member States without requiring transposition into national law.

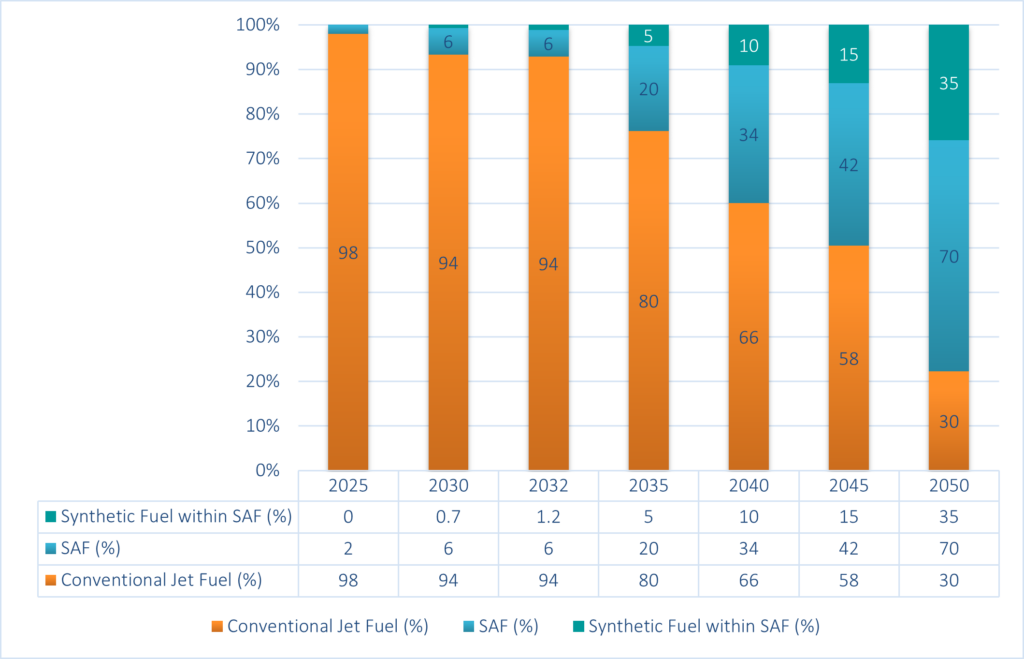

The regulation imposes binding SAF blending obligations on aviation fuel suppliers, requiring them to progressively integrate SAF into the aviation fuel supplied at EU airports. The mandated SAF share begins at 2% in 2025 and will increase incrementally to 70% by 2050, of which a dedicated sub-target for synthetic aviation fuels starts at 0.7% in 2030, reaching 35% by 2050 (see Figure 2). For instance, the goal for 2040 is to achieve a 42% share of SAF in the aviation fuel supplied to EU airports, with 15% of that being synthetic.

To be eligible, SAF must comply with the sustainability and emissions reduction criteria set out in RED I. Acceptable SAF sources include advanced biofuels, synthetic fuels derived from renewable hydrogen, and recycled carbon aviation fuels. Fuel suppliers may also utilize hydrogen for direct aircraft propulsion or synthetic low-carbon fuels.

Within this regulatory framework, synthetic fuels—particularly e-kerosene—are set to play an increasingly prominent role, with a specific mandate ensuring their integration into the fuel mix.

EU airport operators are required to facilitate access to SAF, while aviation fuel suppliers, airports, and aircraft operators must systematically collect and report data to the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and national competent authorities to ensure regulatory compliance.

The regulation further establishes enforcement mechanisms, designating national competent authorities responsible for supervision. Fuel suppliers failing to meet their SAF blending obligations will face financial penalties and must compensate for any shortfall by supplying the missing volume the following year.

By setting clear, long-term SAF quotas through 2050, the ReFuelEU Aviation regulation creates a stable and predictable market framework, reinforcing the EU’s ambition to achieve a more sustainable aviation sector.

Figure 2: SAF Mandate Levels in the ReFuelEU Directive

Incentives for SAF Production and Innovation

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and Financial Incentives for SAF

In addition to the ReFuelEU Aviation regulation, the EU’s climate strategy for the aviation sector is reinforced by the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), established under Directive 2003/87/EC. As a “cap-and-trade” mechanism, the EU ETS aims to progressively reduce greenhouse gas emissions by setting a cap on total emissions while allowing market- based trading of emission allowances. Initially, free allowances were allocated to aircraft operators based on the average emission of the sector and their historical performance. In 2023, approximately 22.5 million aviation allowances were allocated for free, while about 5.7 million were auctioned.

To accelerate decarbonization, the EU has initiated a phased reduction of free emission allowances for aircraft operators:

- In 2024, free allowances were reduced by 25%;

- In 2025, they will be further cut by 50%;

- By 2026, all free allowances will be phased out, requiring operators to fully cover their emissions through auctioning.

This transition is designed to incentivize the adoption of SAF, as airlines can lower their compliance costs by integrating SAF into their fuel mix. To support this shift, the EU has introduced targeted financial incentives within the EU ETS framework:

- A dedicated SAF allowance mechanism provides 20 million allowances (valued at approximately €1.7 billion) until 2030, rewarding aircraft operators based on SAF usage. This mechanism helps bridge the price gap between conventional aviation fuel and SAF. SAF remains significantly more expensive to produce. However, by reducing compliance costs for airlines under the EU ETS, it makes SAF adoption more financially viable, supporting the transition to cleaner aviation fuels while maintaining competitiveness in the sector.

- SAF that meets RED sustainability criteria is attributed zero emissions under the EU ETS, reducing the number of allowances airlines must purchase.

Beyond emissions trading, the EU has also introduced monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) measures for non-CO₂ aviation effects, with additional policy proposals expected by 2028.

Financial Support Mechanisms for SAF Development

Recognizing the financial and technological challenges associated with SAF production, the EU has established several funding instruments to support research, innovation, and large-scale deployment:

- EU Innovation Fund (EUIF): A €40 billion fund aimed at de-risking SAF production across various technology readiness levels. For example, the Innovation Fund awarded in 2023 a €167 million grant to the Biorefinery Östrand project, which seeks to develop, construct, and operate the world’s first large-scale biorefinery dedicated to producing renewable SAF and naphtha, in Östrand, Sweden.

- Horizon Europe: The EU’s flagship €95.5 billion research and innovation program, which funds SAF-related projects.

- InvestEU: A €26.2 billion initiative supporting sustainable infrastructure investments, including SAF production facilities. One of the most notable projects funded by InvestEU is the INERATEC synthetic fuel production facility in Frankfurt. Backed by a €70 million investment, this initiative is supported by a €40 million venture loan from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and a €30 million non-repayable grant from Breakthrough Energy Catalyst. The funding will help develop Europe’s largest carbon-neutral synthetic fuel plant, set to open in 2025.

- Clean Aviation Joint Undertaking: A €1.7 billion public-private partnership between the European Commission and the aeronautics industry to accelerate the development of new aviation technologies.

Projections and Insight

While the ReFuelEU Aviation regulation establishes a robust framework and clear mandates for SAF adoption, several policy areas will require further clarification and potential amendments. The regulation’s overall timeline is generally aligned with industry expectations, but additional interventions may be necessary to ensure a smooth and effective implementation:

- Penalty enforcement and cost volatility: The current penalty mechanism for suppliers failing to meet SAF quotas is directly tied to SAF costs, which remain highly volatile due to potential supply shortages. If SAF prices surge, penalties could become unsustainable, adding financial pressure on suppliers while delaying compliance. Additionally, without a price cap mechanism, rising SAF costs could impact air travel affordability, potentially triggering public and industry backlash.

- Exploring a tradable SAF system: Under Article 15 of ReFuelEU, the European Commission is mandated to assess additional measures to enhance SAF market liquidity and ensure supply stability. One key consideration is the creation of a book-and-claim system, which would enable fuel suppliers and aircraft operators to purchase SAF credits and allocate them flexibly across EU airports. As of January 2025, the Commission’s report on these measures remains pending.

Beyond regulatory refinements, the political landscape in the EU is evolving, with recent electoral shifts favoring parties historically opposed to Green Deal policies. As EU policymakers shift their focus toward an Industrial Deal, maintaining strong momentum for SAF adoption will be critical. Ensuring a stable regulatory environment and continued financial support will be essential to securing the long-term success of SAF integration within the aviation sector.

The effectiveness of SAF regulations in the EU stems from the fact that they are binding, compelling operators to take immediate action and enhance their performance.

Despite its relatively high cost, airlines and operators are eager to contribute and even exceed their obligated SAF targets as early as possible. They understand that this is the only way to assert themselves in the market and to ensure the long- term sustainability and viability of the industry, which must adapt to greener practices to secure its future.

United States of America

The U.S. SAF Landscape

Current Status and Future Developments

Aviation represents roughly 3.3% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and jet fuel consumption is forecasted to increase by 2-3% annually through to 2050. This obviously presents significant opportunities for SAF investment, and the market has responded: projects have been announced in recent years that are projected to meet over 10% of U.S. jet fuel demand. Nonetheless, the biggest challenge SAF faces in the U.S. is that it is not cost-competitive with fossil jet fuel. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, SAF currently costs two to ten times more than fossil jet fuel. Consequently, the federal and state incentives discussed in this section are playing and will continue to play a critical role in the growth of SAF in the U.S.

Federal Support for SAF

The U.S. government supports SAF development in several ways: annual renewable fuel regulatory mandates; tax policy; and grants. Several of these incentives are in flux, however, given the shift in the balance of political power in the U.S. Congress and the White House.

- Regulatory Mandates:

- The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issues annual regulations under the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program that require the national pool of transportation fuel to contain a certain percentage of alternative fuels such as SAF. Production and use of biofuels under these mandates is tracked using a system of tradeable credits (Renewable Identification Numbers or RINs). Among other requirements, eligible SAF must have lifecycle GHG emissions that are at least 50% below a 2005 fossil fuel baseline.

- Although compliance with the program’s mandates falls on fossil fuel producers and importers, RINs implicitly subsidize biofuels such as SAF. Depending upon the feedstock and production process, SAF can generate RINs that may be used to meet the biomass-based diesel, advanced biofuel or cellulosic biofuel mandates and value of the RIN varies by type. RINs generated by producing SAF can be “stacked” with federal tax credits for SAF, such as those provided by the 2022 IRA, as well as state credits relevant to SAF.

- Tax Policy:

- The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) has a significant impact on the SAF market in the U.S. by offering comprehensive support to encourage the production and adoption of this fuel. Instead of setting mandates, the IRA offers SAF credits for qualified neat fuels and provides grants for SAF production and distribution.

- The IRA supports SAF through two credits. First, IRA created a new SAF blender’s tax credit under Internal Revenue Code section 40B, available through to the end of 2024. Then, from January 1, 2025 through to December 31, 2027, the IRA made available a new technology neutral production credit for clean fuels including SAF, the section 45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit.

- The section 45Z credit provides a tax credit for the production of clean fuels that are “suitable for use in a highway vehicle or aircraft” and meet a specified threshold for emissions reductions. The credit is worth up to $1.00 per gallon for transportation fuels and $1.75 or more per gallon for SAF, provided that prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements are met. The 45Z credit is claimed by the producers of SAF, rather than the blenders, but can be transferred or sold to third parties as a means of monetizing the credit.

- Since August 2022, significant work has been done by a multi-disciplinary task force including the U.S. Treasury, the IRS, the Energy Department, the Federal Aviation Administration, and the White House to implement the section 45Z credit and publish tax guidance. Most recently, on January 10, 2025, the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service released Notice 2025-10 and Notice 2025-11, establishing an intent to propose regulations and clarifying annual emissions rates for the credit. At the same time, the 119th Congress is currently reviewing tax legislation that may include revisions to several clean energy tax credits established by the IRA, including section 45Z. As a result, airlines, SAF producers, and conventional energy companies are queuing up to talk to Congress and Trump tax officials about the future of federal tax support for clean fuels, since the current production credit is set to expire at the end of 2027.

- Grants:

- IRA Section 40007 establishes a grant program for eligible U.S. entities involved in SAF production, transportation, blending, or storage, administered by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) through the Fueling Aviation’s Sustainable Transition (FAST) grants program.

- Section 324 of the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for 2023 allows the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) to pilot SAF usage, with a plan to be implemented by FY2028, while permitting waivers under certain conditions.

- The Consolidated Appropriations Act for 2023 and 2024 authorize discretionary grants for airport infrastructure that supports SAF’s distribution and storage, provided they meet the 50% lifecycle GHG reduction requirement.

- The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Energy for America program also provides grants and loan guarantees to rural businesses and agricultural producers for renewable energy projects, including SAF production facilities.

State Incentives for SAF Production and Innovation

- State-level policies further support SAF production and consumption by allowing producers to generate and sell credits to fossil jet fuel suppliers. In 2009, California established the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) to reduce transportation sector GHG emissions in the state and develop a range of low- carbon and renewable alternatives to reduce petroleum dependency. This market-based program sets an annual average carbon intensity (CI) benchmark for all fuels – fossil and renewable – produced or imported into the state. Fuels with a CI below the benchmark (such as eligible SAF) generate credits that producers can sell to other fuel producers in the state as a revenue stream. Oregon, Washington, and New Mexico have adopted similar fuel programs.

In other states – Illinois, Minnesota, and Nebraska – per-gallon SAF production tax credits promote SAF alignment with national objectives.

Projections and Insight

By 2030, domestic SAF production is expected to reach 3 billion gallons annually – a 130-fold increase from 2030 consumption. By 2050, production could rise to 35 billion gallons per year, reflecting a 12-fold increase from the 2030 target.

The shift towards SAF represents a long-term transition in the aviation industry. Given the international nature of air travel, SAF is a clean fuel whose market drivers are largely insulated from the political swings of the US; and American airlines and airports will need to access this fuel to comply with global emissions standards. Driven by discretionary grants from the FAA, significant investments in airport infrastructure for SAF distribution and storage are anticipated. This could lead to an improved supply chain and logistics, facilitating broader SAF availability at major airports by 2025. Increased funding through grants and tax credits may accelerate research and development of new SAF feedstocks and production technologies, enhancing efficiency and reducing costs. This could also lead to advancements in alternative feedstocks, potentially doubling production efficiency by 2030. As government initiatives and incentives ramp up, it is likely that the market share of SAF in total jet fuel consumption will increase significantly from the current less than 0.1%. Projections estimate reaching 5 -10% market share by 2030, depending on regulatory support and industry adoption.

The incentives enacted under the IRA constitute a good beginning in establishing the support necessary for overcoming barriers to SAF adoption. With investors comparing the short three-year timeline of the IRA’s section 45Z clean fuel production credit to ten-year timelines for other clean energy technologies, producers and airlines are making a long-term legislative extension of the credit a top priority for 2025. State level initiatives, like the California LCFS program, look to play a critical role in driving SAF adoption. Other states may follow suit, creating a patchwork of supportive policies that could incentivize producers while also fostering competition among states for SAF leadership.

Conclusion: Comparative Analysis of SAF

Regulatory Frameworks in the UK, EU, and US

The regulatory approaches adopted by the UK, EU, and US to promote SAF reflect distinct policy priorities, economic

structures, and aviation market dynamics. Whilst all three jurisdictions recognize the need to scale SAF production to achieve net-zero aviation emissions, their methods for incentivization, mandate enforcement, and industry engagement exhibit some notable divergences.

Key Similarities

Despite differences in policy mechanisms, several overarching themes emerge across all three jurisdictions:

- Mandatory Blending Requirements: The UK, EU, and US each employ a mix of blending mandates and incentives to encourage SAF adoption. The UK’s SAF Mandate (starting at 2% in 2025 and increasing to 22% by 2040) aligns with the EU’s ReFuelEU Aviation Regulation, which also begins at 2% in 2025 but escalates to 70% by 2050. Although the US lacks a direct federal blending mandate, the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) and state-level Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) programs create market-driven demand for SAF.

- Financial Incentives: Each jurisdiction incorporates financial incentives to lower SAF’s production costs and bridge the price gap with fossil-based jet fuel. The UK’s proposed Revenue Support Mechanism, the EU’s SAF Allowance Mechanism under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), and the US’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) tax credits all aim to de-risk SAF investment. Notably, the US offers the most aggressive tax-based support via the Section 45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit, which directly rewards SAF producers.

- Technology-Specific Targets: Recognizing the need for diversification in SAF production pathways, the UK and EU establish dedicated quotas for Power-to-Liquid (PtL) fuels and synthetic fuels, whereas the US allows greater flexibility in feedstocks, as seen in its Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) and LCFS programs. The UK’s PtL obligation has similar aims to the EU’s sub-target for synthetic fuels, indicating a shared commitment to emerging technologies.

- Market-Based Compliance Mechanisms: Each jurisdiction incorporates a credit trading system to enhance compliance flexibility. The UK’s Renewable Transport Fuel Certificates (RTFCs), the EU’s ETS allowances and (if to be applied) book-and-claim system, and the US’s RIN (Renewable Identification Number) market under the RFS facilitate compliance while stimulating a secondary market for SAF credits.

Key Differences

Despite these similarities, the jurisdictions differ in several key respects:

- Direct v Market-Based Approach:

- The EU and UK impose direct mandates on fuel suppliers, ensuring binding obligations for SAF blending. The UK’s buy-out mechanism acts as a penalty for non-compliance, while the EU enforces fines and requires compensation for missed SAF quotas.

- The US primarily relies on market-driven incentives, with no direct SAF blending mandate at the federal level. Instead, state-based programs such as California’s LCFS and financial incentives like the IRA credits encourage voluntary SAF adoption.

- Policy Longevity and Stability:

- The EU offers the longest regulatory certainty, with ReFuelEU Aviation’s SAF mandates extending to 2050. The UK’s SAF Mandate provides clarity through 2040 but leaves open questions regarding future expansion.

- The US approach is, potentially, more politically vulnerable. The IRA’s Section 45Z tax credit is set to expire by the end of 2027, raising questions about long-term investor confidence. This contrasts with the EU’s more predictable long-term regulatory trajectory.

- Scope of SAF Eligibility and Feedstock Restrictions

- The UK and EU impose stricter sustainability criteria, progressively limiting HEFA (Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids) (or similar) feedstock eligibility. The UK caps HEFA at 92% by 2027, declining to 35% by 2040, while the EU limits food-based biofuels to prevent indirect land-use impacts.

- The US allows broader feedstock eligibility, including corn ethanol-derived alcohol-to-jet SAF, which the EU explicitly excludes. This reflects the political influence of the US agricultural sector, leading to a pragmatic approach to scaling SAF production with available resources.

- Enforcement Mechanisms and Market Oversight

- The EU employs oversight through the European Union Aviation Safety Agency and national regulatory bodies, ensuring strict compliance through direct penalties. The UK SAF Mandate will be administered by the UK’s Department for Transport and will be responsible for enforcing the scheme with power to revoke certificates or issue civil penalties.

- The US relies on tax compliance mechanisms and voluntary participation in state-based LCFS (or similar) markets, which, as an incentive-driven approach results inleading to comparatively less stringent enforcement as can be expected in the EU and UK.

Comparative Insights and Future Implications

Each jurisdiction’s SAF strategy reflects its unique regulatory philosophy and economic priorities. The EU’s highly structured, mandate-driven approach aims to achieve rapid SAF integration but places cost burdens on fuel suppliers and buyers. The UK’s hybrid model, combining mandates with revenue support mechanisms, seeks to balance regulatory certainty with investment incentives. Meanwhile, the US favors a market-driven, incentive-based model, fostering innovation but opening up potential regulatory uncertainty due to shifting political landscapes.

This evolving landscape reflects a multi-faceted approach, balancing stringent emissions reduction targets with mechanisms that incentivise investment and production. The UK has introduced ambitious mandates within its Jet Zero strategy, while the EU’s Fit-to-55 package integrates SAF quotas through the ReFuelEU Aviation initiative.

Meanwhile, the USA leverages tax credits and grant programs under initiatives like the Inflation Reduction Act to stimulate domestic SAF production. These diverse regulatory tools aim to address the significant challenges of scaling SAF, including high production costs, limited feedstock availability, and infrastructure constraints.

Looking ahead, international policy harmonization will be critical to ensuring the global scalability of SAF. The International Civil Aviation Organization and industry stakeholders may push for greater alignment between EU- style mandates and US-style incentives, potentially influencing future SAF policies. Additionally, ongoing bilateral agreements between the UK, EU, and US on carbon accounting, emissions reporting, and SAF certification will play a crucial role in fostering a globally integrated SAF market.

Despite their differences, the UK, EU, and US share the common goal of scaling SAF production to enable a net zero aviation future. While their paths to achieving this differ, their collective efforts will be instrumental in driving the technological and economic transformation needed for sustainable aviation. As regulatory frameworks evolve, continued cross-border collaboration and policy adjustments will be essential to maximizing SAF’s impact on global decarbonization goals.

Additional Authors: Parker A. Lee, Brittany M. Pemberton, and Timothy J. Urban.

/>i

/>i