In the case of Anuj Jain Interim Resolution Professional for Jaypee Infratech Ltd. v Axis Bank Limited Etc.[i] the Supreme Court of India (“SC”) has laid down detailed principles for the identification of a preferential transaction which could be voided under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (“Code”). The judgment is of importance to investors and lenders, as the approach of the SC in the case, highlights the risk of a transaction being set aside and the diligence which should be exercised by investors and lenders going forward.

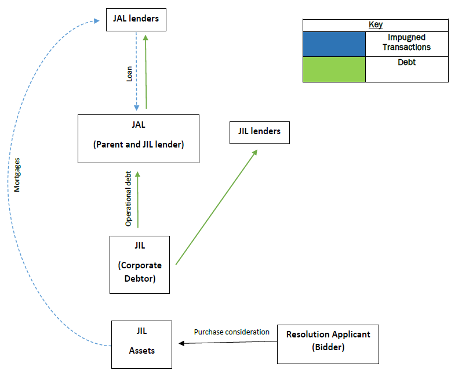

The SC had held that certain security interests created by a corporate debtor Jaypee Infratech Ltd. (“JIL”) in favour of the lenders of its holding company Jayprakash Associates Ltd. (“JAL”) were preferential transactions. The SC viewed these transactions in a holistic manner to arrive at its conclusion, and has laid down a precedent which would deter corporate entities from putting in place complex and innovative structures to contract out of the preferential nature of transactions.

It is important to note that in this case the security interest was created in favour of JAL’s lenders, however the ultimate beneficiary of the transactions was JAL. Accordingly, the SC has not simply looked at the entity in whose favour security interest has been created, but also the ultimate beneficiary of the transactions, to arrive at its conclusion.

The Supreme Court also held that in circumstances where the security provider and the borrower are different persons/entities, then the lender would not qualify as a financial creditor of the security provider during its insolvency unless the security provider is a guarantor or surety of the borrower. This holding would deprive such lenders from exercising the rights of a financial creditor during the corporate insolvency resolution process (“CIRP”), including being a part of the committee of creditors and exercising the attendant rights.

Furthermore, while the SC has ordered that the security interest created by JIL be released and discharged, it has not provided any clarity on the status of the loan amounts furnished by the lenders on the strength of such security interest.

Factual Background

The corporate debtor JIL is a special purpose vehicle set up by its parent entity JAL for certain construction and development and infrastructure projects. JAL holds approximately 71% of the shares of JIL and had provided operational debt to JIL to the tune of 261 crores.

JIL mortgaged some of its properties to secure the loans advanced by certain banks to JAL (“Impugned Transactions”). IDBI Bank Ltd., a creditor of JIL, filed an application to initiate the CIRP in respect of JIL. Pursuant to this, the CIRP commenced and a resolution professional was appointed to manage the affairs of JIL. The resolution professional upon noticing the Impugned Transactions filed an application before the NCLT, seeking declarations that the Impugned Transactions were fraudulent, undervalued and preferential transactions under the Code. The NCLT allowed the application, and ordered (1) the release and discharge of the security interested created by JIL and (2) the properties mortgaged by way of the Impugned Transactions be deemed to be vested in JIL (“NCLT Order”). However, the lenders of JAL preferred an appeal from the NCLT Order. The NCLAT allowed the appeals and set aside the NCLT Order (“Impugned Order”). Various appeals were filed against the Impugned Order before the Supreme Court, which brings us to the present judgment.

A comprehensive diagram representing the above parties and transactions is given below.

Issues before the SC

-

Whether the Impugned Transactions were liable to be avoided, being preferential, undervalued and fraudulent, under the provisions of the Code;

-

Whether the lenders of JAL could be recognized as financial creditors of JIL, given that the loans to JAL were secured by mortgage of properties of JIL;

Judgment

Whether the Impugned Transactions were liable to be avoided, being preferential, undervalued and fraudulent, under the provisions of the Code

-

Meaning of Preferential Transaction

At the outset, the SC analyzed the evolution of the preferential transactions, legal dictionary definitions of such transactions, commentaries on such transactions, and the treatment of such transactions under the bankruptcy laws of the UK and the US, to highlight the basic tenets of such transactions.

The court held that the basic concept of a ‘preference’ as per the definitions set out in law dictionaries was the act of paying, by an insolvent debtor, the whole or part of their claims, to the exclusion of the rest [of the creditors].

The court also observed that the concept of a ‘preference’ and the principles relating to the avoidance of preferential transactions had evolved under various mercantile, insolvency and bankruptcy laws over time as follows:

-

Various jurisdictions had defined such transfers as transactions ‘where the insolvent debtor makes [a] transfer to or for the benefit of a creditor so that such beneficiary would receive more than what it would have otherwise received through the distribution of bankruptcy estate.’

-

The US Bankruptcy Code and the UK Insolvency Act, 1986 also contained measures for the recovery of preferential transfer from the transferee, and for avoidance of preferential transfers, respectively.

-

The court further noted that the ‘relevant time’/look back period played a crucial role in such measures for avoidance, and such periods were shorter with respect to connected/related parties.

- Ingredients of Preferential Transactions

The SC after a detailed analysis of Section 43 of the Code held that a transaction entered into by a corporate debtor would be deemed to have given a preference to a creditor if:

-

The transaction involved a transfer of property of the corporate debtor for the benefit of a creditor, for or on account of an antecedent financial debt owed by the corporate debtor to the creditor;

-

The transfer had the effect of putting the creditor in a more beneficial position than it would have been, in the event of distribution of assets of the corporate debtor in the usual course as per the liquidation waterfall provided under Section 53[ii] of the Code;

-

Such transactions were entered into either (1) during the two year period preceding the insolvency commencement date in case the beneficiary was a related party, or (2) during the one year period preceding the insolvency commencement date in case the beneficiary was an unrelated party. This time period was referred to as the ‘look back’ period.

-

The transactions were not excluded from the purview of preferential transactions on one of the following two grounds:

-

Any transfer made in the ordinary course of business/financial affairs of the corporate debtor and the transferee;

-

The transaction creating a security interest secured a new value in the property acquired by the corporate debtor, i.e., in monetary terms, or in terms of goods, services, new credit, or secured the release of a previously transferred property.

The SC held that if a transaction satisfied the abovementioned ingredients, preference would be deemed/presumed to have been given by the corporate debtor to a creditor.

A deeming fiction would be created, whereby any such transaction would be considered preferential in nature, irrespective of whether the parties to the transaction intended or even anticipated to be so. The court distinguished between (i) provisions under the Companies Act, 2013 which contained provisions on fraudulent preference (Section 328) and transfers not in good faith (Section 329), and (ii) Section 43 of the Code, which did not contemplate a requirement of intent/fraud to fall within the parameters of the provision.

It is important to note that under the Companies Act, 1956 as well, there were provisions on fraudulent preference (Section 531), and provisions for the avoidance of such preferential transfers (Section 531 A). However, no deeming provision for preferential transfers akin to Section 43 of the Code, under which the intent of a party is irrelevant for the purposes of determining whether the transfer is preferential.

The SC further held that although the provisions relating to preferential transactions had to be strictly construed, the underlying purpose and object of the provisions could not be lost while interpreting it.

- Whether the Impugned Transactions amounted to Preferential Transactions

The SC held that the creation of mortgage by JIL vide the Impugned Transactions satisfied the ingredients of a preferential transaction under the Code as follows:

- The transfer of property/interest thereof was for the benefit of a creditor:

JAL, as an operational creditor, stood much lower in priority than the other creditors of JIL, and other stakeholders in case of distribution of assets of JIL during liquidation under Section 53[iii] of the Code.

Vide the Impugned Transactions, JAL had been put in an advantageous position vis-à-vis JIL’s other creditors as follows:

- JAL received working capital from the lender banks in favour of whom JIL had mortgaged its assets;

- The Impugned Transactions had the effect of reducing JAL’s liability towards its own lenders;

The SC observed that a necessary corollary of the beneficial position of JAL was a corresponding disadvantage borne by JIL’s other creditors, as the assets encumbered by JIL vide the Impugned Transactions would not form part of the corpus of available assets which could be subject to liquidation.

- The transfer was on account of an antecedent financial/operational debt or other liabilities owed by the corporate debtor:

The SC noted that JIL owed antecedent operational debts and other liabilities towards JAL. Not only was JAL the largest shareholder in JIL, JAL had been providing financial, technical and strategic support to JIL in various ways. JAL had also extended bank guarantees in favour of JIL, and entered promoter support agreements with JIL’s lenders to assist JIL in meeting its obligations towards the latter.

- The transfer was for the benefit of a related party during the look back period

The SC held that (1) JAL was a related party of JIL and (2) all of the Impugned Transactions were entered into during the two-year period preceding the insolvency commencement date of August 9, 2017. Accordingly, the Impugned Transactions were entered into during the look back period prescribed under the Code for related parties.

- The transfer was not in the ordinary course of business/financial affairs of the corporate debtor and the transferee

Section 43(3) exempts transactions from the purview of preferential transactions if they are a

The court accepted the contention of the appellants that the word ‘or’ appearing in this section was required to be read as ‘and,’ so as to cover those transfers made in the ordinary course of business of the corporate debtor. The court held that, the purport of Section 43 (i.e., to annul preferential transactions, and minimize loss to other creditors by such transactions), appeared to be directed towards the corporate debtor’s dealings. Only if such transactions were entered into in the ordinary course of the corporate debtors business/financial affairs, could they be regarded as not creating a preference in favour of one creditor over the other.

If such transfers were examined with reference to the ordinary course of business/financial affairs of the transferees alone, such transfers could get excluded from the ambit of preferential transactions, which could not have been the intent of Section 43.

The court further observed that JIL was a special purpose vehicle for the construction and development of land, execution of housing projects, etc. Accordingly, routinely mortgaging assets to secure debts of its holding company (i.e., vide the Impugned Transactions) could not be considered to be the ordinary course of business of JIL.

Accordingly, the SC held that the Impugned Transactions were preferential transactions under Section 43 of the Code. The court held that it was not necessary to deal with the issues of whether the Impugned Transactions were also undervalued and/or fraudulent.

Whether the lenders of JAL could be recognized as financial creditors of JIL;

Certain lenders of JAL filed applications under Section 60(5)[iv] of the Code seeking to be recognized as financial creditors of JIL on account of the creation of mortgages in their favour vide the Impugned Transactions.

A ‘financial creditor’[v] has been defined under the Code as one to whom a ‘financial debt’[vi] is owed, or to whom such debt has been legally assigned/transferred to.

A ‘financial debt’ has been defined, in turn, as a ‘debt along with interest, if any, which is disbursed against the consideration for the time value of money…’ The definition of ‘financial debt’ also includes various transactions, among them contracts of guarantee.[vii]

The aforesaid lenders of JAL sought to argue that JIL owned them a mortgage debt as a guarantee obligation, and accordingly the Impugned Transactions were ‘financial debts’ under the Code. Therefore, the lenders sought to argue that they were ‘financial creditors’ of JIL.

However, the SC held that JAL’s lenders could not be classified as financial creditors as follows:

- Impugned Transactions lacked Ingredients of financial debt: The court relied upon the case of Pioneer Urban Land and Infrastructure Ltd. & Anr. v Union of India & Ors[viii] in which the SC had considered the elements of a 1) disbursement 2) borrowing and 3) consideration for time value of money as essential ingredients of a ‘financial debt’ under the Code.

The court noted that the transactions listed in the definition of ‘financial debt’ under the Code could only be considered financial debts if they carried these essential ingredients.

The court held that JAL’s lenders had 1) not disbursed any amounts in favour of JIL, nor 2) had such consideration been for the time value of money. Therefore, JIL did not owe any ‘financial debt’ to the lenders, and such lenders could not be classified as ‘financial creditors’ under the Code.

- Role of financial creditor: The court further relied upon the case of Swiss Ribbons Pvt. Ltd. & Anr. v Union of India & Ors[ix] in which the court had elaborated upon the role of a financial creditor. The court in Swiss Ribbons held that a financial creditor was a guardian entity that was involved in the functioning of the corporate debtor from the beginning, and whose interests were intrinsically interwoven with the well-being of the corporate debtor.

Keeping this in mind, the SC held that the position and role of an entity merely having a security interest (i.e., JAL’s lenders) over assets of the corporate debtor could not be considered financial creditors, as their only interest was realising the value of the security, whereas a financial creditor would also be interested in the rejuvenation and revival of the corporate debtor.

Accordingly, the court held that JAL’s lenders could not be considered financial creditors of JIL. However, the court held that such lenders may fall within the definition of ‘secured creditors,’ by virtue of the security created by the corporate debtor in their favour.

Takeaways for Investors/lenders

-

No requirement of creditor/debtor relationship between corporate debtor and transferee, if transfer is for ultimate benefit of a creditor of the corporate debtor

In this case, the lenders of JAL did not provide any direct financial assistance to JIL. Accordingly, there was no creditor/debtor relationship between JAL’s lenders and JIL. However, the court held that although there was no creditor-debtor relationship between the lender banks and JIL, the Impugned Transactions had the ultimate effect of working towards the benefit and advantage of JAL, who obtained loans and financing through such transactions. The Impugned Transactions created a security interest for the benefit of JAL.

The SC held that the absence of a creditor-debtor would not be decisive of the question of whether a transaction was preferential, if the ultimate beneficiary of transactions was a creditor of the corporate debtor. In this case, the transaction could still be construed to be a preferential transaction.

The SC has therefore given a purposive construction to the provisions governing preferential transactions under the Code, by holding that transfers by a corporate debtor to a third party who is not its creditor may still get caught within the net of Section 43 and be liable to be avoided during CRIP, if it is found to be preferential.

For example, if Part A (the corporate debtor) has transferred its property to a lender (Party B), and Party B has used this property to provide financial assistance to Party C, and Party C has used the finances for the ultimate benefit of Party D, who is a creditor of Party A, this entire web of transactions may be considered a preferential transaction for the purposes of the Code.

The effect of the SC’s decision has also been to change the status of JAL’s lenders from secured creditors to unsecured creditors. The court has upheld the NCLT Order to release and discharge the security interest created vide the Impugned Transactions and vest the mortgaged assets back in JIL. Accordingly, JAL’s lenders are no longer secured creditors and can, at best, simply seek a refund of the loan amounts furnished to JAL in lieu of such security. However, if JAL is unable to pay such amounts, JAL’s lenders would have to stand in line along with the rest of JAL’s creditors to seek the proceeds of from the sale of JAL’s liquidation assets under Section 53 of the Code.[x] However, please see point (iii) below in this regard.

- Onus on lenders to carry out diligence on borrowers, as well as entity providing security

As discussed, the SC interpreted Section 43(3) as exempting transactions from the purview of preferential transactions if they are a transfer made in the ordinary course of business or financial affairs of the corporate debtor ‘and’ the transferee

JAL’s lenders (the transferees in this case), expressed concern that holding the transactions as preferential with reference to the ordinary course of business of the corporate debtor, would impact upon a large number of financing arrangements entered into by such banks, which would have a devastating impact upon the economy.

However, the SC dismissed these contentions as unfounded and emphasized that bankers and other financial institutions were required to carry out a due diligence while determining whether to advance a loan, by 1) studying the viability of the proposed enterprise and 2) ensuring that the security against such loans was genuine, adequate and available for enforcement at any point in time. If such bankers/financial institutions were advancing loans against the security interest provided by a third party (and not the borrower), they were required to carry out a further diligence on such third parties to ensure that 1) the third party security was viable and not hit by any law and 2) the third party itself was in good financial health, and not indebted.

Accordingly, the onus to prevent preferential transaction has been put on the lenders, rather than the borrowers. Therefore, lending institutions, (including private equity or venture capital funds), are required to ensure that their due diligence spans both the entity to whom a loan is provided, as well as the entity which is furnishing the security interest, and the relationship between the two entities. Such institutions must be extremely careful and assess the end use of funds, the financial health of the entity providing the security interest, etc.

Considering that the court has 1) put such an onus on the lenders, as well as 2) held that a transaction may considered preferential in nature, irrespective of whether the transaction was in fact intended or even anticipated to be so, it would be critical for lenders to put enough correspondence with the investee entity during such diligence, to cover any future inquiries into such transactions as suppression of information by the investee entity.

- Status of JAL’s lenders

The court has also held that JAL’s lenders cannot be considered financial creditors of JIL, however they could be considered secured creditors, on the strength of the mortgage created vide the Impugned Transactions.

The implication of this is that lenders who have been provided security interest by corporate debtors will not be members of the committee of creditors of the latter nor exercise the attendant rights of such members. It is also unclear in what sequence such lenders will receive the proceeds of liquidation, since the liquidation waterfall provided under Section 53 of the Code makes a distinction between secured and unsecured creditors, as opposed to a distinction between financial/operational or other types of creditors.

- Consequence of avoidance of Impugned Transactions

The SC has upheld the NCLT Order, directing (1) the release and discharge of the security interested created by JIL and (2) the properties mortgaged by way of the Impugned Transactions be deemed to be vested in JIL

However, while the SC has ordered the release of the security interest, it has not provided any clarity on the status of the loan amount provided by JAL’s lenders to JIL, i.e., whether (i) the loan subsists, (ii) whether the loan amounts are to be refunded, (3) whether the agreements providing such loans are to be regarded as void ab initio, etc. There is accordingly no clarity on how JAL’s lenders can recover their loan amounts.

In case lenders have provided a loan amount under a master facility agreement on the strength of a mortgage created under a separate mortgage deed, they should insert appropriate clauses in the master facility agreement making the grant of the loan contingent on the continued availability of the security interest.

[i] Civil Appeal Nos. 8512 - 2019

[ii] Section 53 - Distribution of assets

1[(1) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in any law enacted by the Parliament or any State Legislature for the time being in force, the proceeds from the sale of the liquidation assets shall be distributed in the following order of priority and within such period and in such manner as may be specified, namely:--

(a) the insolvency resolution process costs and the liquidation costs paid in full;

(b) the following debts which shall rank equally between and among the following:--

(i) workmen's dues for the period of twenty-four months preceding the liquidation commencement date; and

(ii) debts owed to a secured creditor in the event such secured creditor has relinquished security in the manner set out in section 52;

(c) wages and any unpaid dues owed to employees other than workmen for the period of twelve months preceding the liquidation commencement date;

(d) financial debts owed to unsecured creditors;

(e) the following dues shall rank equally between and among the following:--

(i) any amount due to the Central Government and the State Government including the amount to be received on account of the Consolidated Fund of India and the Consolidated Fund of a State, if any, in respect of the whole or any part of the period of two years preceding the liquidation commencement date;

(ii) debts owed to a secured creditor for any amount unpaid following the enforcement of security interest;

(f) any remaining debts and dues;

(g) preference shareholders, if any; and

(h) equity shareholders or partners, as the case may be.

(2) Any contractual arrangements between recipients under sub-section (1) with equal ranking, if disrupting the order of priority under that sub-section shall be disregarded by the liquidator.

(3) The fees payable to the liquidator shall be deducted proportionately from the proceeds payable to each class of recipients under sub-section (1), and the proceeds to the relevant recipient shall be distributed after such deduction.

Explanation.--For the purpose of this section--

(i) it is hereby clarified that at each stage of the distribution of proceeds in respect of a class of recipients that rank equally, each of the debts will either be paid in full, or will be paid in equal proportion within the same class of recipients, if the proceeds are insufficient to meet the debts in full; and

(ii) the term "workmen's dues" shall have the same meaning as assigned to it in section 326 of the Companies Act, 2013 (18 of 2013).]

[iii] ibid

[iv] 60 (5) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in any other law for the time being in force, the National Company Law Tribunal shall have jurisdiction to entertain or dispose of--

(a) any application or proceeding by or against the corporate debtor or corporate person;

(b) any claim made by or against the corporate debtor or corporate person, including claims by or against any of its subsidiaries situated in India; and

(c) any question of priorities or any question of law or facts, arising out of or in relation to the insolvency resolution or liquidation proceedings of the corporate debtor or corporate person under this Code.

[v] 5 (7) "financial creditor" means any person to whom a financial debt is owed and includes a person to whom such debt has been legally assigned or transferred to

[vi]5(8) "financial debt" means a debt along with interest, if any, which is disbursed against the consideration for the time value of money and includes--

(a) money borrowed against the payment of interest;

(b) any amount raised by acceptance under any acceptance credit facility or its de-materialised equivalent;

(c) any amount raised pursuant to any note purchase facility or the issue of bonds, notes, debentures, loan stock or any similar instrument;

(d) the amount of any liability in respect of any lease or hire purchase contract which is deemed as a finance or capital lease under the Indian Accounting Standards or such other accounting standards as may be prescribed;

(e) receivables sold or discounted other than any receivables sold on non-recourse basis;

(f) any amount raised under any other transaction, including any forward sale or purchase agreement, having the commercial effect of a borrowing;

4[Explanation.-- For the purposes of this sub-clause,--

(i) any amount raised from an allottee under a real estate project shall be deemed to be an amount having the commercial effect of a borrowing; and

(ii) the expressions, "allottee" and "real estate project" shall have the meanings respectively assigned to them in clauses (d) and (zn) of section 2 of the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016 (16 of 2016);]

(g) any derivative transaction entered into in connection with protection against or benefit from fluctuation in any rate or price and for calculating the value of any derivative transaction, only the market value of such transaction shall be taken into account;

(h) any counter-indemnity obligation in respect of a guarantee, indemnity, bond, documentary letter of credit or any other instrument issued by a bank or financial institution;

(i) the amount of any liability in respect of any of the guarantee or indemnity for any of the items referred to in sub-clauses (a) to (h) of this clause;

[vii] Section 5(8)(h), the Code

[viii] (2019) 8 SCC 416

[ix] (2019) 4 SCC 17

[x] ibid

/>i

/>i