On March 21, 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States heard oral argument in Abitron Austria GmbH, et al. (“Abitron et al.”) v. Hetronic International, Inc. (“Hetronic”)[i] on an issue it has not squarely addressed in seven decades: the extraterritorial reach of the Lanham Act, the comprehensive trademark statute in the United States. SCOTUS is considering:

Whether the [Tenth Circuit] court of appeals erred in applying the Lanham Act extraterritorially to petitioners’ foreign sales, including purely foreign sales that never reached the United States or confused U.S. consumers.

SCOTUS’ answer to this question will be crucial for both United States trademark owners and, indeed, companies engaged in commerce anywhere in the world. Importantly, SCOTUS is poised to determine the extent to which American trademark holders are able to recover damages for infringing conduct that occurs abroad. Based on their questioning, the Justices seemed nearly unanimous in their opinion that, in the modern internet-driven world, the Lanham Act has at least some extraterritorial application. All Justices probed the potential limits and pitfalls of various potential tests for when the Lanham Act should apply to conduct outside the United States.[ii]

The Hetronic – Abitron Dispute

Hetronic involves a trademark dispute between Hetronic, an American company (the plaintiff below), and foreign companies, and one individual, based in Germany and Austria (collectively, Abitron et al., the defendants below). The parties are in the business of radio remote controls used to control heavy-duty construction equipment. They previously had a relationship where Hetronic manufactured products, and Abitron et al. acted as Hetronic’s European distributors. Somewhere along the line, Abitron et al. began to manufacture its own products—identical to Hetronic’s products—and sell them under Abitron et al.’s marks, mostly in Europe.

After a trial in the Western District of Oklahoma, a jury found that Abitron et al. had willfully infringed Hetronic’s marks and awarded over $90 million directly related to Abitron et al.’s Lanham Act violations. This amounted to nearly all of Abitron et al.’s worldwide sales. In fact, approximately 97% of Abitron et al.’s sales occurred abroad to foreign consumers such that American consumers were never actually exposed to the infringing marks in connection with those sales. That being said, approximately €1.7 million worth of Abitron et al.’s goods ended up in the United States via resale.[iii]

In affirming the jury’s verdict, the Tenth Circuit held that the €1.7 million in foreign sales that reached the United States was sufficient to demonstrate a substantial effect on United States commerce. The Tenth Circuit also found it significant that Abitron et al. diverted tens of millions of dollars of foreign sales from Hetronic that would otherwise have flowed into the United States (i.e., a “diversion-of-sales” theory). The Tenth Circuit found that these conclusions, combined with evidence of actual confusion of United States consumers, were sufficient to demonstrate an “impact within the United States of a sufficient character and magnitude as would give the United States a reasonably strong interest in the litigation.”[iv] The Tenth Circuit held that the Lanham Act applied extraterritorially to reach all of the Petitioner’s infringing conduct, wherever in the world that conduct actually occurred.[v] In doing so, the Tenth Circuit observed that Steele “leaves much unanswered about the extent of the Lanham Act's extraterritorial reach.”[vi]

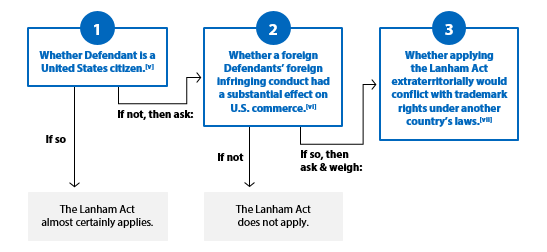

The Tenth Circuit explained that determining whether the Lanham Act applies extraterritorially as against a foreign defendant requires a multi-step inquiry[vii][viii]

The Parties’ Arguments

At oral argument, counsel for Abitron argued that, generally, the Lanham Act simply does not reach trademark infringement that occurs outside the United States. He cited the principle that trademarks have always traditionally been territorially limited. For Abitron’s counsel, the fact that the defendant in Steele was an American citizen, was key to the decision in that case.[xi] Multiple Justices, with the notable exception of Justice Samuel Alito, pushed back on this assertion, but none harder than Justice Sonia Sotomayor. She stated, “I don’t see why overturning Steele or making it depend on the citizenship of the defendant is important.” She also mused that “the fact that [an accused infringer] choose[s] to deliver those goods at the border outside the United States or into the U.S., to me, should make no difference.”

Counsel for Hetronic argued that the Supreme Court, and Congress at least by its acquiescence, had repeatedly reaffirmed that the Lanham Act can apply extraterritorially. Attempting to put to rest Justice Clarence Thomas’s apparent concern about overreach, counsel noted that in the real world, personal jurisdiction would, as it has over the past 70 years, serve as an effective limit on the Lanham Act’s extraterritorial reach. Advocating for the affirmation of the Tenth Circuit’s decision, Hetronic argued that a “substantial effect” on United States commerce is sufficient to invoke the Lanham Act.[xii] Justice Alito also probed into the outer limits of Hetronic’s position, particularly because of the historically geographical nature of trademark rights. Counsel for Hetronic acknowledged that each nation is the arbiter of its own trademark law, but pointed again to the longstanding practice of the extraterritorial application of that law. Interestingly, in light of today’s seemingly hyper-competitive world, he raised the specter of a United States citizen being completely without a remedy when the infringement occurs in a hostile nation, or at least one that does not respect intellectual property rights.

Counsel from the Solicitor General’s office advocated for more of a middle ground. They argued that the Tenth Circuit’s holding was too sweeping, and that absent a clear affirmative indication of extraterritorial application, the inquiry should shift to whether infringement abroad causes consumer confusion in the United States, rather than focusing on economic effects and international comity.[xiii] Some Justices, particularly, Justice Neil Gorsuch, balked at the idea of this issue being a matter of whether to focus on an infringer’s conduct, the injury to the mark-holder to be prevented, consumer confusion, or the intent of the accused infringer. To laughter in the audience, Justice Gorsuch opined that trying to zero in on the Lanham Act’s “focus” was akin to a “legislative séance,” in which he seemed to want no part.

Perhaps the star of the judicial show in this case was the Court’s newest member, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. She posed a series of escalating hypotheticals, culminating with a savvy group of American students studying abroad in Germany. In her first hypothetical, a German manufacturer, with no intent to ever sell in the United States, sells knockoff “Coach” bags in Germany. To that, counsel for Abitron et al. confidently stated that liability would not attach against the manufacturer. Next, a group of American college students studying abroad in Germany buy the knockoff “Coach” bags and come back to the United States with them, where people who see them become confused. Counsel, once again, stated that the manufacturer would not be liable. Finally, the American students flex their capitalistic muscles and purchase $100,000 worth of the knockoff “Coach” bags and sell them in the United States. Even then, counsel for Abitron et al. answered that Coach could sue the students, but not the manufacturer.

The other Justices seized on this helpful hypothetical, particularly Justice Alito who tweaked the hypothetical to probe the Government’s position about proximate cause and the relevant foreseeability of the goods entering United States commerce. Justice Jackson jumped back in the fray, questioning why a manufacturer’s intent has any relevance under the Lanham Act. The Government, under challenging clarifying questions from Justices Gorsuch and Jackson, stated no intent to import a mens rea or intention requirement in to the Lanham Act.

Conclusion

Given the Justices’ questions at oral argument, at least a majority (if not all) of the Justices appear to accept that the Lanham Act should have at least some extraterritorial application. Interesting questions remain. Will SCOTUS overturn or limit Steele? Will SCOTUS adopt the step-by-step approach of the Tenth Circuit? Will SCOTUS adopt more of a true multifactor balancing test, as multiple Courts of Appeals have done in the past?[xiv] Will SCOTUS adopt the two-step test proposed by the Government? What will the language and focus of the standard be? Will SCOTUS opine on the issue of the diversion-of-foreign sales theory of damages?

One thing is certain: this upcoming SCOTUS decision will surely affect Lanham Act jurisprudence in a way that clients will have to consider in our increasingly interconnected world. Dinsmore attorneys will be following this issue closely and advising our clients on any new developments in this nuanced area of trademark law.

FOOTNOTES

[i] 10 F.4th 1016 (10th Cir. 2022).

[ii] The Supreme Court last directly addressed the Lanham Act’s extraterritorial application in Steele v. Bulova Watch Co., 344 U.S. 280 (1952) (“Steele”). In Steele, the defendant was a citizen and resident of the United States who was operating a watch business that strategically moved his business to Mexico. Reasoning that the trademark “Bulova” was not registered in Mexico, defendant secured the rights to the Bulova name in Mexico and began to import watch parts from Switzerland and the United States. Defendant then sold watches in Mexico under the Bulova mark. Plaintiff, the Bulova Watch Company, began receiving complaints from confused customers who needed repairs of defective watches that often turned out to be the defendant’s product. Id. at 284-85. There, the Supreme Court concluded that the Lanham Act applied to defendant’s conduct, reasoning that the United States is permitted to govern the conduct of its own citizen, even while abroad. Id. at 285-86. The Court further noted that the inferior watches were liable to damage Bulova’s reputation in both the United States and foreign markets. Id. at 286.

[iii] While there was some dispute between the parties about the extent to which Arbitron et al. made sales directly to United States consumers, any such sales did not bear on the 10th Circuit’s analysis of the extraterritoriality issue. See Hetronic, 10 F.4th at at 1042-43.

[iv] Id. at 1046.

[v] Id.

[vi] Hetronic, 10 F.4th at 1033-34.

[vii] Id. at 1042.

[viii] Id. at 1036-37.

[ix] Id. at 1037.

[x] Id. at 1037-38.

[xi] Citing the need for clarity in this area, in their Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, Abitron et al. identified six distinct tests used by the Circuit Courts of Appeals, all differing in meaningful ways such that these approaches are “splintered.” See Petitioners’ Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, filed Jan. 21, 2022 at 14. Also of note, the United States, submitting a brief as an amicus curiae in support of the petition for certiorari, agreed with Petitioner and the Tenth Circuit that there is, in fact, a meaningful circuit split of authority. See Brief amicus curiae of United States, filed Sept. 23, 2022.

[xii] In its opposition to Abitron’s Petition, Hetronic argued that no actual meaningful Circuit split exists and the supposed differences in approaches between the Circuits were merely “semantic.” Hetronic further argued that all of the supposedly different tests are actually just different ways of asking same two-part question, namely: (1) did the foreign conduct harm U.S. commerce?; and (2) would enforcement conflict with international trademark law?

[xiii] “An act of accommodation or courtesy. Comity generally refers to any gesture of good will among equals. In particular it refers to an act by one state or sovereign made for the convenience of another, though not under a legal obligation to do so, even though a reciprocal benefit might be implied by the doing.” Comity, Bouvier Law Dictionary (The Wolters Kluwer Bouvier Law Dictionary Desk Ed. 2012).

[xiv] Vanity Fair Mills, Inc. v. T. Eaton Co., 234 F.2d 633, 642 (2d Cir. 1956); Int’l Cafe, S.A.L. v. Hard Rock Cafe Int’l, (U.S.A.), Inc., 252 F.3d 1274, 1278 (11th Cir. 2001); Aerogroup Int’l, Inc. v. Malboro Footworks, Ltd., 152 F.3d 948 (Fed. Cir. 1998), published in full-text format at 1998 U.S. App. LEXIS 7733 (per curiam); Liberty Toy Co. v. Fred Silber Co., No. 97-3177, 1998 U.S. App. LEXIS 14866, at *19-21 (6th Cir. 1998).

/>i

/>i