The year we also saw intriguing legal debates over the protectability of architectural designs as trademarks. As we venture into a new year, these changes will not only impact legal practices, but also influence the creative and strategic decisions in the design and real estate industries.

Deciphering Defenses to Copyright Infringement Claims in Real Estate Cases: A Closer Look at the Zillow and Dirt.com Cases of 2023

Two high-stakes cases in 2023, involving Zillow and Dirt.com, underscored the complexity of navigating the fair use doctrine, which is a statutory defense to copyright infringement claims, within the real estate realm.

Zillow, the well-known online real estate marketplace, found itself embroiled in a copyright legal battle with VHT, Inc., a premier provider of digital marketing services for the real estate industry in the case VHT, Inc. v. Zillow Group, Inc., 69 F.4th 983 (9th Cir. 2023). At the heart of the case was Zillow's allegedly unauthorized use of nearly 2,700 of VHT's photographs in Zillow property listings on its website and app. Zillow defended its actions by arguing that its use of the photographs constituted fair use because it transformed the works by cropping and tagging them for their online search engine. Zillow also argued that the photographs were registered as a compilation, such that VHT should only be eligible for a single award of statutory damages, rather than individual awards of statutory damages for each photograph found to have been infringed.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed with Zillow on both points. First, the court found that Zillow’s use was not fair, as the added searchability additions to the photographs did not fundamentally change the original purpose of the photos. Second, the court found that while the 2,700 photographs were registered with the US Copyright Office as a single compilation work, the registration protected each image individually, such that VHT could seek separate statutory damages awards for each image infringed.

This finding has potentially huge implications for the value of real estate photography infringement cases as the Copyright Act permits statutory damages awards ranging from $750 to $30,000 per infringed work (which can be reduced to no less than $200 for innocent infringements), and up to $150,000 per work for willful infringement. In other words, if Zillow had won this argument, potential damages could have been as low as $750 or as high as $150,000 for the whole case. But since it lost, potential damages will likely have a floor of over $540,000 and could go as high as $405 million dollars should willful infringement be found for each work. In practice though, these numbers are typically balanced with considerations of market value and equity. Here, the Ninth Circuit affirmed a finding of statutory damages of $800 for 2,312 of the accused images and $200 per image for the 388 innocently infringed photos, bringing the total damages award to over $1.9 million dollars.

In another case tackling the fair use doctrine, Dirt.com, a celebrity real estate gossip site, was sued by the photographer Brandon Vogts for copyright infringement. Dirt.com had allegedly utilized Vogt's photographs without permission in connection with articles about high profile celebrity real estate transactions. Dirt.com defended its actions in court by asserting that its usage of the photographs was transformative, and thus fell under the doctrine of fair use. In particular, Dirt.com claimed that by making minor changes to the photographs and featuring them in conjunction with articles, Dirt.com was adding new meaning or context to the original work to render them transformative and therefore “fair use.” The court rejected this argument, reiterating that the unauthorized use of copyrighted materials, even when altered or used in a digital medium, could constitute copyright infringement. The court also considered the plaintiff’s affirmative motion for summary judgment and found as a matter of law that defendants’ use was not fair and that they were liable for copyright infringement. See Vogts v. Penske Media Corp., 2023 WL 7107276(C.D. Cal. Aug. 30, 2023).

Both cases underscore the risks of being named a defendant in a copyright infringement action for using photographs, even in arguably transformative manners, without permission. They also serve as a reminder that the fair use defense is a nuanced, multi-factor doctrine that must be considered in the context of a unique set of facts and on a case-by-case basis. Lastly, they provide support for the frequent practice of registering large groups of photographs as compilation works and demonstrate that in at least the Ninth Circuit, doing so will not limit to statutory damages remedies available if infringement is found.

Navigating the Legal Labyrinth of Architectural Copyright

This year witnessed some significant developments in architectural copyright law in the context of contract interpretation and bankruptcy proceedings. Two cases in the Fifth and Eighth Circuit Courts of Appeals grappled with complex questions of copyright infringement when expanding on pre-existing works in these settings.

The first case, Cornice & Rose Int'l, LLC v. Four Keys, LLC, 76 F.4th 1116 (8th Cir. 2023), involved a rare analysis of the Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act of 1990 (AWCPA), which extended copyright protection to original and non-functional elements of architectural designs. First Security Bank & Trust Company purchased an incomplete building approved by the bankruptcy court in the property owner’s Chapter 7 liquidation proceeding. The question was whether the bank infringed the architectural firm Cornice & Rose’s copyright in the building design by completing the building without the architectural firm’s permission and using their original copyrighted plans to do so. The lower court granted summary judgment to the defendants, finding, among other things, that even if the old plans were copied to complete the building, such acts were protected under Section 120(b) of the Copyright Act, which permits building owners to authorize building alterations without triggering infringement liability even if the alterations are based on copyrighted pre-existing plans. The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals then affirmed and ruled in favor of the bank for alternative procedural reasons.

In the case of Loeb-Defever v. Mako, L.L.C., 2023 WL 5611042 (5th Cir. Aug. 30, 2023), the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court ruling that favored a real estate developer defendant who had utilized an architect's preliminary design schematics to develop a senior living facility. The court determined that the contract between the parties provided the defendant with an express, nonexclusive license to use the schematics and to create derivative works from them. Moreover, the court elaborated that this license encompassed the right to engage third parties to execute the project. Notably, the court found that the contract term “reproduce” included the right to create derivative works. Given this holding, companies seeking to limit future uses of their designs would be wise to expressly exclude the right to prepare derivative works from contracts.

DesignWorks Homes vs. Columbia House of Brokers Realty Case: Exploring the Interplay of Form and Function

The US Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit ruled in Designworks Homes, Inc. v. Columbia House of Brokers Realty, Inc., 2023 WL 7278744 (W.D. Mo. Sept. 29, 2023) that Section 120(a) of the Copyright Act is not a defense to infringement claims based on the copying and publishing of floor plans depicting, in part, underlying copyrightable works.

The case involved a dispute over the copyright of an architectural design referred to as the "triangular atrium design with stairs" by Designworks Homes, Inc. and Charles Lawrence James. The defendant, Columbia House of Brokers Realty, Inc., was contracted to sell a house located in Missouri, which had been designed and constructed by Designworks and included the triangular atrium design with stairs. In their marketing endeavors to sell the house, the defendant hired a third party to measure the house's interior and create a drawing of the structure's floor plan. Designworks argued that this resulting floor plan violated their rights under the Copyright Act because it included a depiction of their copyrighted triangular atrium design with stairs. Among other things, the defendant argued that the creation of a floor plan incorporating an underlying design protected by copyright law does not amount to copyright infringement due to Section 120(a), a rarely used provision of the Copyright Act. That provision permits the creation, distribution, or public display of pictures or other visual depictions of a work if the building that contains the work is located or can be seen from a public place.

The lower court agreed with the defendants and granted their motion for summary judgment, finding that the floor plans were “pictorial representations” of homes and thus protected under Section 120(a) of the Copyright Act. But on appeal, the Eighth Circuit disagreed and reversed and remanded the case. The appellate court independently concluded that this provision does not apply to functional things, like floor plans, as opposed to works of artistic expression like a painting. Therefore, it held that Section 120(a) does not provide a defense to copyright infringement claims against real estate entities for generating and publishing floor plans for the homes they list for rent or sale.

Architectural Trade Dress: Implications of TTAB's Rulings for Trademark Registrations for Building Shapes and Designs

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) issued two precedential opinions that provided new perspectives on whether and when building designs can be protected as marks. These rulings — Palace Del Rio and Seminole Tribe of Florida — implicate the critical questions of acquired and inherent distinctiveness and their application to exterior architectural designs. It is black letter trademark law that trade dress found to be inherently distinctive (including product packaging) are per se registrable, while trade dress without inherent distinctiveness (including product designs) may only be registered with adequate evidence of acquired distinctiveness. But the exact parameters of how these rules apply to building shapes and designs has been somewhat unsettled at the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) until now.

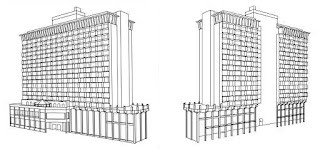

In In re Palacio Del Rio, Inc., 2023 U.S.P.Q.2d 630 (TTAB 2023) (precedential), The Hilton Palacio del Rio in San Antonio, Texas unsuccessfully attempted to register the designs of the “River” and “Street” sides of its hotel building (which included common architectural elements like columns and arches), citing their "unique and readily recognizable design.” The USPTO examiner refused the applications, taking the position that the applied-for marks were not distinctive and would not be perceived as service marks. In response, the applicantargued that the entire modular design of its hotel was distinctive due to its unique assembly of basic elements, which they claimed created a recognizable overall appearance to customers. The applicant also claims that the designs had acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f). On appeal of the refusal, the TTAB sided with the examiner and affirmed rejection of the applications. According to the Board, the modular design shown in the applications was not distinctive or unique enough to warrant trademark protection, but rather contained well-known and commonly used forms of ornamentation. The Board also found that the evidence the applicant submitted in support of its Section 2(f) acquired distinctiveness claim — articles discussing the hotel’s construction and declarations from consumers — were inadequate to support that claim.

images of Hilton Palacio del Rio’s submission of its design to the TTAB

In contrast, in In re Seminole Tribe of Florida, 2023 U.S.P.Q.2d 631 (TTAB 2023) (precedential), the Seminole Tribe successfully obtained trademark protection for its guitar-shaped Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Hollywood, Florida. The USPTO examiner initially refused the registration on the basis that the design was a non-distinctive trade dress and failed to function as a service mark. In response, the Seminole Tribe argued that this design was akin to product packaging and that the guitar shape was not only unique as a building design in general but was also distinctive among buildings that house hotels, restaurants, and casinos. The Tribe also claimed acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f) and provided evidence of trade dress registrations that the USPTO had granted for other building designs unique to their respective industries. On appeal of the examiner’s refusal, the TTAB reversed course and ruled in favor of the Seminole Tribe. In granting the registration to the Tribe, the Board held that the guitar-shaped building design due was inherently distinctive for the applied-for services, and that it was unique and did not contain a well-known form of ornamentation.

Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Hollywood, FL’s unique guitar shaped hotel

The TTAB's contrasting rulings in the Palace Del Rio and Seminole Tribe of Florida cases underscore the importance of establishing inherent or acquired distinctiveness in order to secure trademark protection for architectural designs. While the Seminole Tribe case makes clear that highly unusual architectural designs may qualify for protection as inherently distinctive, the Palace Del Rio case provides a cautionary reminder that commonly-used motifs may not be found inherently distinctive or protectable even with evidence of acquired distinctiveness. In sum, together these cases stand for the rule that the shape of a building design or a building design can be deemed inherently distinctive and registrable at the USPTO without evidence of acquired distinctiveness, but only if the shape is distinctive and unusual for that type of building.

Brooke M. Delaney contributed to this article.

/>i

/>i