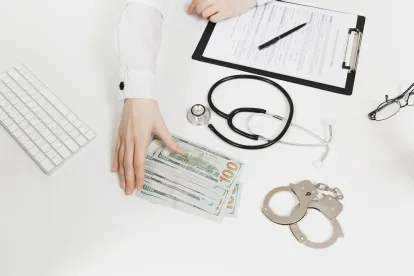

Healthcare employers, human resource directors, in-house counsel, and other professionals who routinely deal with contracting issues should understand that physician employment arrangements are unlike other employment contracts. Physician employment (and independent contractor) agreements pose unique and heightened risks that deserve utmost caution.

Often, providers concentrate on addressing issues of general importance (e.g., termination provisions and restrictive covenants) and those that frequently cause friction between employers and physicians (e.g., clinical contact time commitments and on-call coverage). However, unique risks arise from the potential application of a multitude of fraud and abuse laws, including:

-

The physician self-referral law [42 U.S.C. § 1395nn], commonly referred to as the Stark Law. Stark prohibits physicians (MD or DO, dentist, podiatrist, optometrist, or chiropractor) from referring patients for certain, designated health services payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician, or an immediate family member, has a financial relationship, unless an exception applies. Stark is a strict liability statute and proof of specific intent to violate the law is not required to find a violation.

-

The Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) [42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)], a criminal law, prohibits the knowing and willful payment of “remuneration” (anything of value, in whatever form) to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by federal health care programs. The AKS has broader coverage than Stark; it is not limited to certain services.

-

The False Claims Act (FCA) [31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-3733], makes it illegal to submit claims for payment to Medicare or Medicaid that you know or should know are false or fraudulent. “Knowing” is defined to include not only actual knowledge, but also where the person acts in deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of the information.

Potential Penalties

Penalties for violating Stark, the AKS, or FCA can be devastating to providers, large and small.

Potential penalties include:

-

Stark – No payment for a service resulting from a prohibited referral and an obligation to refund improper payments. In addition, there is the potential for civil money penalties of up to $15,000 per improper claim and/or exclusion from federal health care programs.

-

AKS – Conviction of a felony, with fines of up to $100,000, imprisonment of up to 10 years, or both. The government also may assess civil penalties under the Civil Monetary Penalties Law [42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a] for violations of the AKS of up to $100,000 per violation or exclude the entity from federal health care programs.

-

FCA – Civil penalties per false claim of between $11,181 and $22,363, plus three times the government’s actual damages. A claim for payment that violates Stark or the AKS are deemed to be false claims under the FCA.

Enforcement

Only the government can enforce Stark and the AKS directly — neither statute provides private citizens with the right to enforce them through a private right of action.

However, the FCA not only provides for a private right of action (a “qui tam” case), but, if successful, the private litigant (“relator”) is entitled to receive 15%-25% of the damages awarded to the government. This significantly increases the risk of Stark or AKS enforcement through the FCA, as these cases often involve millions, tens of millions, or even hundreds of millions of dollars in alleged damages. This is a powerful incentive for individuals to become relators and for attorneys to pursue qui tam cases on the relator’s behalf. A relator can be almost anyone with knowledge of the alleged fraud but is often a current or former employee of the organization alleged to have violated the FCA through Stark or the AKS.

How real is the threat of enforcement?

In fiscal year 2018 the U.S. Department of Justice obtained more than $2.8 billion in settlements and judgments from civil fraud and abuse cases, with $2.5 billion involving the healthcare industry.

Example

How quickly can the potential damages escalate?

The oft-cited United States v. Rogan, 459 F. Supp. 2d 692 (N.D. Ill. 2006), upheld on appeal in 2008 [517 F.3d 449 (7th Cir.)], provides a good example of the basic math:

-

The case involved referrals for services from two physicians who were held to have violated Stark, the AKS, and the FCA;

-

The hospital controlled by the defendant submitted 1,822 claims to Medicare and Medicaid resulting from those referrals;

-

The total value of the claims was $16,864,677.50, which, when trebled as required under the FCA, totaled $50,594,032.50;

-

Civil penalties of $7,500 per claim also were assessed, totaling $13,665,000 (pursuant to the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act Improvements Act of 2015, the minimum civil penalties have since more than doubled); and

-

The final judgment upheld on appeal was for $64,259,032.50.

This exemplifies the way damages will rapidly escalate in any FCA case based on Stark and the AKS.

/>i

/>i