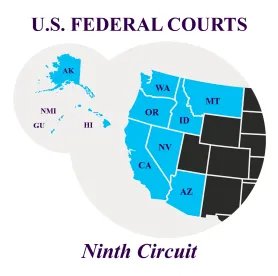

A split Ninth Circuit panel recently reversed the dismissal of claims against P.F. Chang’s regarding the chain’s use of the term “krab mix” in the ingredients list for certain sushi rolls. Kang v. P.F. Chang’s China Bistro, No. 20-55138 (9th Cir. Feb. 9, 2021).

Plaintiff claimed he purchased P.F. Chang’s “krab mix” sushi rolls because the term “krab mix” led him to believe the rolls contained at least some real crab meat, when in fact they contained none. P.F. Chang’s countered that reasonable consumers would be tipped off by the fanciful spelling of “krab,” as well as the fact that other items on the same page of the P.F. Chang’s menu listed “crab” (spelled correctly) in their ingredients. Accordingly, P.F. Chang’s argued, a consumer confronted with both “crab” and “krab mix” on the same page would not be misled into believing they are the same. The district court agreed, and dismissed plaintiff’s claims as implausible on their face. In doing so, the court analogized to a prior decision finding no reasonable consumer would be misled into believing “Froot Loops” contain “Fruit.” McKinnis v. Kellogg, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 96106 (C.D. Cal. 2007).

The Ninth Circuit reversed, relying primarily on Williams v. Gerber Prods. Co., 552 F.3d 934 (9th Cir. 2008). In Williams, the defendant sold products labeled “Fruit Juice Snacks” with images of fruits on the front label. The ingredients list on the side of the box disclosed that the product did not actually contain juice from any fruits pictured on the packaging. The Williams Court found the defendant could not immunize itself against prominent, misleading front-label claims by disclosing the truth about the product’s ingredients elsewhere. The majority held the same to be true in this case—just as the Williams court believed a consumer might not look beyond representations on the front of a box to discover an ingredients list displayed elsewhere on the packaging, the majority here concluded a P.F. Chang’s customer might not look beyond the phrase “krab mix” to discover the term “crab” used elsewhere on the same menu.

In a persuasive dissent, Judge Bennett criticized the majority for failing to give the ordinary California consumer enough—or any—credit. Importantly, Judge Bennett pointed out that the standard for misrepresentation is not whether the “least sophisticated” or “most gullible” consumer would be misled. According to Judge Bennett, reasonable consumers in the food industry are prudent enough to know that fanciful spellings materially change the meaning of a word, since this kind of advertising is now commonplace in the food industry. For instance, “cavi-art” is not caviar, “Froot Loops” are not fruit, and “tofurky” is not turkey. Judge Bennett concluded “nothing about ‘krab mix’ suggests that the sushi rolls will contain real crab,” and “wishful thinking on the plaintiff’s part” does not make for a plausible claim. Judge Bennett also reiterated the district court’s finding that the context in which “krab mix” appeared (i.e., in close proximity to other items labeled “crab”) should clue consumers in.

P.F. Chang’s joins the ranks of Williams and Bell v. Publix Super Markets, 982 F.3d 468 (2020) as decisions likely to be embraced by the advertising class action plaintiffs’ bar. However, this decision will not change the status quo that it is both common and entirely appropriate for courts to dismiss as a matter of law complaints alleging unreasonable understandings of advertising claims which are cured by disclosures elsewhere on the advertising. There are several recent and notable decisions from the Second and Ninth Circuits recognizing this principle. For example:

-

In Fink v. Time Warner, the Second Circuit affirmed the dismissal of plaintiffs’ false advertising complaint, acknowledging that it is “well settled that a court may determine as a matter of law that an allegedly deceptive advertisement would not have misled a reasonable consumer,” and that “the presence of a disclaimer or similar clarifying language may defeat a claim of deception.” 714 F.3d 739, 741-42 (2d Cir. 2013).

-

In Jessani v. Monini North America, the Second Circuit affirmed the dismissal with prejudice of plaintiffs’ complaint alleging that reasonable consumers would take away the false message that a flavored olive oil truthfully described as “truffle flavored” contains real truffles. 744 F. App’x 18 (2d Cir. 2018). The Court agreed with Monini, who Proskauer represented, that this was simply not a reasonable takeaway in the overall context of its label, and given the absence of truffles on the ingredient list.

-

In Ebner v. Fresh, the Ninth Circuit explained that Williams merely “stands for the proposition that if the defendant commits an act of deception, the presence of fine print revealing the truth is insufficient to dispel that deception.” 838 F.3d 958, 966 (9th Cir. 2016) (emphasis in original). In Ebner, the Ninth Circuit found it was not plausible that reasonable consumers would be deceived as to how much lip balm the defendant’s product contained where the label accurately stated its net weight.

-

In Razo v. Ashley Furniture Industries, the Ninth Circuit held that the “district court properly granted summary judgment on Razo’s claims because a reasonable consumer would have read the unambiguous and truthful disclosures placed on the front and back of Ashley’s DuraBlend hangtag.” 782 Fed. Appx. 632, 633 (9th Cir. 2019).

-

In numerous recent lawsuits against confection makers, federal district courts have dismissed claims alleging defendants’ “white”-labeled sugary goods deceived reasonable consumers into thinking the products contain white chocolate, when they do not. In dismissing these claims, courts noted that the ingredients list on the packaging clearly did not include any mention of “white chocolate.” See our prior coverage of such cases involving Nestle Tollhouse and Ghirardelli.

Further, the dissent warns against the inevitable harm that stems from allowing such implausible claims to proceed further down the litigation path—the cost of defending these claims is not inconsequential, and is ultimately passed onto consumers. It remains to be seen if the Ninth Circuit will come to better appreciate this fact and reverse course as this line of decisions spawns increasing numbers of food labeling suits.

/>i

/>i