Armed with purported copies of invoices showing a defendant purchasing a genuine carpet product at an earlier time, and selling an accused infringing product at a later time, with the later invoice bearing the name of the genuine design, a New York-based design house has brought copyright and trademark infringement litigation against a Georgia company.

On March 8, 2013, Stacy Garcia, Inc. (“SGI”) filed its complaint in the Northern District of Georgia against The Bennett Wardlaw Company (“Bennett Wardlaw”), two individuals believed to be principals at Bennett Wardlaw, and a company owning a Comfort Suites hotel in Louisiana where the infringing carpet is alleged to have been installed.

SGI describes itself on its website as follows: “The Stacy Garcia design house produces designs for textiles, carpeting, wallcoverings, furniture, and lighting, and is known for its innovative design aesthetic and color combinations.” Its complaint adds: “SGI was founded in 2004 and is a leader in the hospitality design industry.”

Exhibit B to the complaint purports to be a copy of U.S. Copyright Registration No. VA-666-463, which recites the “Madison” title, March 1, 2009 as the date of first publication, and April 3, 2009 as the date of registration issuance. Since April 2009, the complaint alleges, SGI and its licensee used the name MADISON as a trademark to identify floor coverings. SGI alleges that “the MADISON Mark has acquired significant secondary meaning and goodwill.”

According to the complaint, in November 2010 Bennett Wardlaw’s predecessor-in-interest “ordered SGI’s genuine Madison Design floor covering for use in a Wingate Inn / Holiday Inn in Vicksburg, Mississippi,” with Composite Exhibit D identified in the complaint as copies of the associated purchase order and invoice.

Then, in May 16, 2012, the complaint alleges, Bennett Wardlaw sold an infringing floor covering to defendant My Investments, Inc. for installation in the Comfort Suites in Louisiana. In the excerpt from the complaint shown below, SGI identifies the carpet on the left as “Genuine Madison Floor Covering,” and the carpet on the right as “Infringing Floor Covering.”

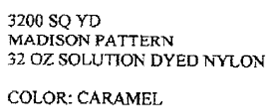

Exhibit E to the complaint purports to be a copy of a Bennett Wardlaw invoice relating to the alleged transaction with My Investments, Inc. That exhibit recites the following text:

SGI alleges that in August of 2012, it learned of the floor covering in that Comfort Suites. Then, according to the complaint, in September 2012, SGI’s its general counsel sent a letter to the defendants asserting copyright infringement and requesting information as to the party from whom the accused floor covering was purchased. In January 2012, SGI alleges, its litigation counsel contacted Bennett Wardlaw and the two individual defendants (“the Wardlaw Defendants”) requesting the same information, but that both its September and January letters went unanswered.

The complaint asserts copyright infringement against all defendants, contributory copyright infringement against the Wardlaw Defendants,[1] false designation of origin under § 43(a) of the Lanham Act arising from the accused use of the MADISON Mark, and state law counts for violation of the Georgia Uniform Deceptive Trade Practices Act (“GUDTPA”) and common law trademark infringement.

The complaint seeks injunctive and monetary relief, including either actual damages plus profits orstatutory damages (enhanced for accused willful infringement) under the Copyright Act, enhanced monetary recovery under the Lanham Act for alleged infringement of the MADISON Mark, and attorneys’ fees under both Acts and GUDTPA.

The case is Stacy Garcia, Inc. v. The Bennett Wardlaw Company, Janice Wardlaw, Christopher Bennett, and My Investments LLC, No. 1:13-cv-0760-MHS, filed 03/08/13 in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division, and assigned to Senior U.S. District Judge Marvin H. Shoob.

[1] “Contributory infringement necessarily must follow a finding of direct or primary infringement. This court has stated the well-settled test for a contributory infringer as ‘one who, with knowledge of the infringing activity, induces, causes or materially contributes to the infringing conduct of another.’ Furthermore, our court explicated that ‘the standard of knowledge is objective: Know, or have reason to know.’” Cable/Home Comm. Corp. v. Network Productions., Inc., 902 F.2d 829, 845 (11th Cir. 1990) (citations and other internal quotation marks omitted).

/>i

/>i