Summary

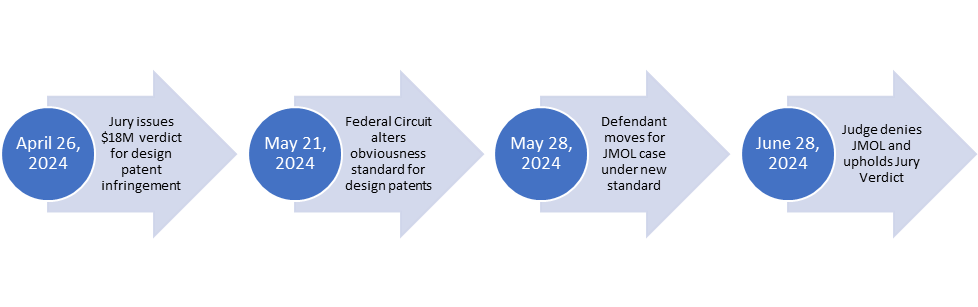

The jury in Cozy Comfort had previously awarded $18 million to plaintiff Cozy Comfort after finding the defendant — a sweatshirt retailer — liable for infringing, among other things, the plaintiff’s design patents claiming a hooded blanket design.

Shortly after this verdict, however, the Federal Circuit in LKQ discarded the preexisting obviousness standard for design patents (the Rosen-Durling test) as “improperly rigid” for requiring “basically the same” prior art references. The LKQ court determined instead that the four-factor obviousness test for utility patents established in Graham and KSR should be applied to design patents as well.

Relying on the LKQ decision, the Cozy Comfort defendant motioned for a new trial, arguing that the plaintiff had “put the Rosen-Durling test front-and-center in making its case for non-obviousness to the jury,” and under the new LKQ standard, the defendant’s obviousness case would have been presented “materially different” at trial. The trial judge refused to set aside the jury verdict.

In denying the motion, Judge Steven Logan recognized that while LKQ aligned the standard for obviousness of design patents with that used for utility patents, the jury instructions had mirrored the Graham factors, which is the “exact analysis for obviousness which LKQ commands.” Simply put, if the KSR application of the more flexible Graham test would yield the same result as the “improperly rigid” Rosen-Durling test, then a verdict issued under the latter should still stand.

Practical Considerations

Going forward, litigants should ensure that any expert opinion they offer on design patent obviousness is rendered under the LKQ standard, and timely challenge those that fail to do so under Daubert. When crafting jury instructions, parties should also make every effort to adopt language consistent with the obviousness analysis that LKQ commands.

/>i

/>i