What You Need To Know In A Minute Or Less

Microplastics, as a seemingly ubiquitous contaminant, have increasingly become the subject of online exposés and class action challenges. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) states on its microplastics research page that, “[m]icroplastics have been found in every ecosystem on the planet, from the Antarctic tundra to tropical coral reefs, and have been found in food, beverages, and human and animal tissue.” With quotes like this, it does feel like microplastics are everything, everywhere, all at once.

This second edition of our environmental, social, and governance-focused Litigation Minute series explores the emerging class action litigation landscape for microplastics, scientific questions about the analysis for and risk of microplastics, and hurdles that may complicate plaintiffs’ abilities to succeed in a challenge.

What Are Microplastics?

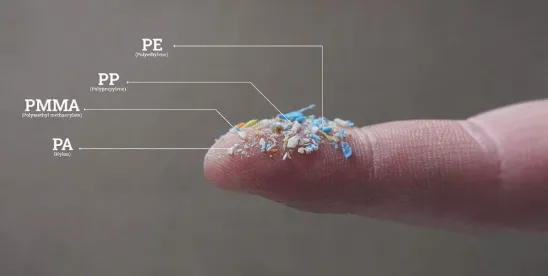

Microplastics are generally defined as small plastic particles ranging in size from 1 nanometer to 5 millimeters. To put these sizes in context, the EPA notes that a strand of human hair is 80,000 nanometers wide and a pencil eraser is about 5 millimeters wide.

Microplastics can include substances that are intentionally added to products and known as primary microplastics, such as exfoliating beads in facial or body scrubs. Microplastics also include secondary microplastics, which are unintentionally formed from larger plastic materials as a result of chemical weathering, mechanical breakdown, or other mechanisms.

Claims Relating to Microplastics

As with claims relating to other alleged contaminants (e.g., heavy metals and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), plaintiffs’ claims relating to harm arising from exposure to microplastics are often attenuated. For example, plaintiffs have alleged spring water described as “100% natural” is mislabeled due to the potential presence of microplastics. Plaintiffs have also alleged that baby bottles and sippy cups described as “BPA Free” are mislabeled because the plaintiffs contend they leach microplastics during heating. Plaintiffs also filed a greenwashing claim against a fitness wear brand that promotes environmental attributes of its products because the products allegedly release microplastics into waterways when laundered.

In each of these cases, the plaintiff does not allege the intentional use of primary microplastics but contends that the potential release of microplastics invalidates claims like “sustainable,” “natural,” or “BPA-free.” Some of the scientific issues implicated by such plaintiffs' claims are discussed below.

Scientific Debate Around Risk

Although microplastics research has hit a fever pitch, with many publications claiming the discovery of microplastics in humans and animals, a definitive correlation between microplastic exposure and adverse human health events has not been established. In addition, it is worth noting that the chemical and structural diversity of microplastics (and the subset of even smaller nanoplastics) can vary in size, shape, polymer type, state of degradation, presence of additives, and other factors.

Historically, global authorities that regulate the materials coming into contact with food such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Food Safety Authority, have assessed much smaller polymer fragments (i.e., those with a molecular weight on the order of approximately 1,000 Daltons or less), as this was the only fraction viewed as having toxicological relevance. Microplastics and even nanoplastics are orders of magnitude larger than this fraction. Regulatory authorities have generally considered microplastics to lack toxicological relevance due to their general inertness and relatively rapid excretion from the body.

Recently, the FDA issued its first public comment on microplastics in food, stating that “current scientific evidence does not demonstrate that levels of microplastics or nanoplastics detected in food pose a risk to human health.”1

Litigation Hurdles

Setting aside health and safety concerns at this stage, there are other threshold issues that complicate a microplastics litigation challenge. In asserting these claims and alleging the presence of microplastics, plaintiffs have frequently cited sources—such as blogs—claiming to have detected microplastics in foods matrices, and plaintiffs do not have access to the underlying data and analysis.

In issuing its first comments on microplastics in food, FDA officials have noted that the lack of standardized methods for detection, quantification, and characterization of microplastics has led to, in their view, the use of “methods of variable, questionable and/or limited accuracy and specificity” to test for microplastics. As a result, factors such as the complex and variable characteristics of these materials, the lack of standardized reference materials, and the absence of validated analytical methods will complicate a plaintiff’s ability to prove that microplastics are even present.

Footnotes

1 Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Foods, US Food & Drug Administration, 24 July 2024

/>i

/>i