This post in our Landmark Montana Supreme Court Decision Series discusses the Montana Supreme Court’s consideration of an insurer’s duty to defend in National Indemnity Co. v. State, 499 P.3d 516 (Mont. 2021).

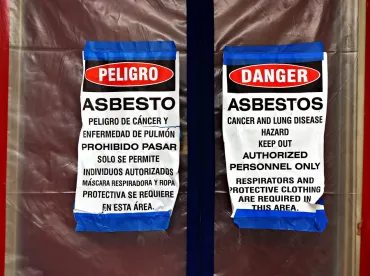

For 67 years, W.R. Grace & Company’s mining operations spread asbestos through the town of Libby, Montana, causing elevated rates of asbestosis and asbestos-related cancer in Libby residents – even among those who never worked in the mine. The Environmental Protection Agency deemed the Libby Mine the “most significant single source of asbestos exposure” in US history.

In 2000, Libby residents began filing lawsuits against the State of Montana, alleging that the State had failed to warn them about the mine’s danger, and this failure contributed to their bodily injuries. Id. at 521-22. The Libby plaintiffs’ asbestos exposures and related injuries had occurred decades earlier, and so the State searched its storage units for records of any potentially applicable insurance policies.

In June 2002, it found the declarations page for a National Indemnity Company policy, which was effective from 1973 to 1975. The policy had an insuring agreement common to commercial general liability policies issued in the mid-1970s:

The company [National Indemnity] will pay on behalf of the insured all sums…to which this insurance applies, caused by an occurrence, and the company shall have the right and duty to defend any suit against the insured seeking damages on account of such bodily injury or property damage, even if any of the allegations of the suit are groundless, false or fraudulent… (Emphasis added.)

The State tendered the claims to National Indemnity immediately, but the State’s letter did not make any specific request that National Indemnity assume its defense or reimburse costs. Id. at 522. At the time, Montana’s motion to dismiss the lead plaintiffs’ lawsuit was pending and fully briefed, so the State was not incurring defense costs. National Indemnity’s adjuster, therefore, found “there was nothing to be done” in response to the State’s tender. But then the plaintiffs appealed Montana’s motion to dismiss win, so the State again began to accrue defense costs.

The State told National Indemnity about the appeal, but continued to handle its own defense as the appeal wended its way to the Montana Supreme Court. In 2005, the Court overturned the dismissal and remanded the lawsuit to the trial court, giving the Libby Mine claimants a chance to pursue their claims against the State.

A flurry of letters between Montana and National Indemnity followed. Most relevant to the Court’s analysis were these:

-

March 17, 2005: The State inquired “whether National Indemnity is accepting this tender and will be providing a defense of the State and providing coverage for these claims,” which had ballooned to 90 claimants.

-

July 18, 2005: National Indemnity agreed to defend the State, but conditioned its defense on a pro-rata time-on-the-risk allocation of defense costs. at 530.

-

November 2005: The State rejected National Indemnity’s conditional offer. at 523.

-

May 10, 2006: National Indemnity expressed its willingness to pay 100 percent of the cost of defending the State, subject to a reservation of rights, but with an intent “to leave no doubt whatsoever regarding the commitment of National Indemnity Company to defend the State.”

In 2012, National Indemnity filed a declaratory judgment requesting, among other things, a ruling that it had no duty to defend the State against the Libby Mine claims. Id. at 525. The Montana Supreme Court affirmed the District Court’s ruling to the contrary: the claims did trigger National Indemnity’s duty to defend, because the complaints alleged the State’s negligence caused bodily injury during the policy period (1973 to 1975).

The Court found National Indemnity’s duty arose in 2002 when the State first contacted National Indemnity and provided copies of the initial complaints against it. Id. at 528. But between 2002 and 2005, National Indemnity satisfied the “necessary substance” of its defense obligations, because the State was handling its own defense. Id. at 530.

Yet, National Indemnity breached its duty to defend in July 2005 when it did not undertake a complete defense in violation of Montana’s “mixed-action rule.” Id. at 531. Under the rule, an insurer must defend the entire action; “limit[ing] its defense responsibility to a pro rata portion of the [] claims violated the Policy and the duty to defend.” Id.

In May 2006, National Indemnity cured its breach by agreeing to defend. At that time, National Indemnity reserved its right to recoup defense costs but did not condition its defense on a recoupment or pro rata allocation. Id. While the majority rule, as confirmed in the Restatement of the Law, Liability Insurance § 24, is that an insurer has no right of recoupment absent an explicit agreement with the policyholder affirming that right, the Court found that Montana law generally supported a right to recoupment.[1] Id.

But then National Indemnity breached its duty to defend again by waiting nearly a decade to file its declaratory judgment action. Id. at 536. The Court explained the significance of the delay:

Given the complexity of the coverage issues, the age of the policy, and the number of potential claimants involved here, litigation of this length [almost another decade’s worth] was foreseeable. A declaratory judgment’s purpose is to discern the extent of coverage under a policy so that an insurer may know the extent of its legal duties relative to the insured. It is not a Sword of Damocles to be hung over the insured’s head throughout the entire course of litigation. In the end, National delayed so long as to prejudice the State by forcing it to litigate and settle cases in coverage darkness. While there is no categorical rule imposing an obligation on an insurer to file a declaratory judgment action within a certain amount of time, we cannot, given these facts, ignore the effect such a decision has on the insured.

Id. at 535 (cleaned up).

Because it breached its duty to defend, National Indemnity (i) was estopped from asserting coverage defenses and (ii) had to pay full defense costs (and indemnity) for claims the State tendered and settled before February 23, 2012, when National Indemnity filed the declaratory judgment action. Id. at 536-37. This decision provides a reminder of the breadth of insurers’ duty to defend and the potential consequences of breaching that duty.

[1] A concurring opinion written by Judge Davies (sitting by designation) and joined by Justice Gustafson cautioned against reading the Court’s opinion as providing insurers a broad “right to recoupment against the average insured in the absence of a policy provision allowing recoupment.” Id. at 548. The concurring judge and justice would have limited the majority’s entertainment of a potential right of recoupment to “the unique facts of this case, which involves sophisticated parties and the application of insurance policies over multiple policy periods.” Id.

/>i

/>i