Recent years have seen many innovative finance mechanisms used in impact investing. Whether in response to decreased government budgets, or due to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) global pandemic, the need for innovation to drive positive impact is greater than ever. This includes not only mobilizing additional capital from the private sector, but also considering how to recycle existing funds for greater sustainability. This article takes a closer look at recoverable grants and analyzes when they might be appropriate, including how they differ from forgivable loans.

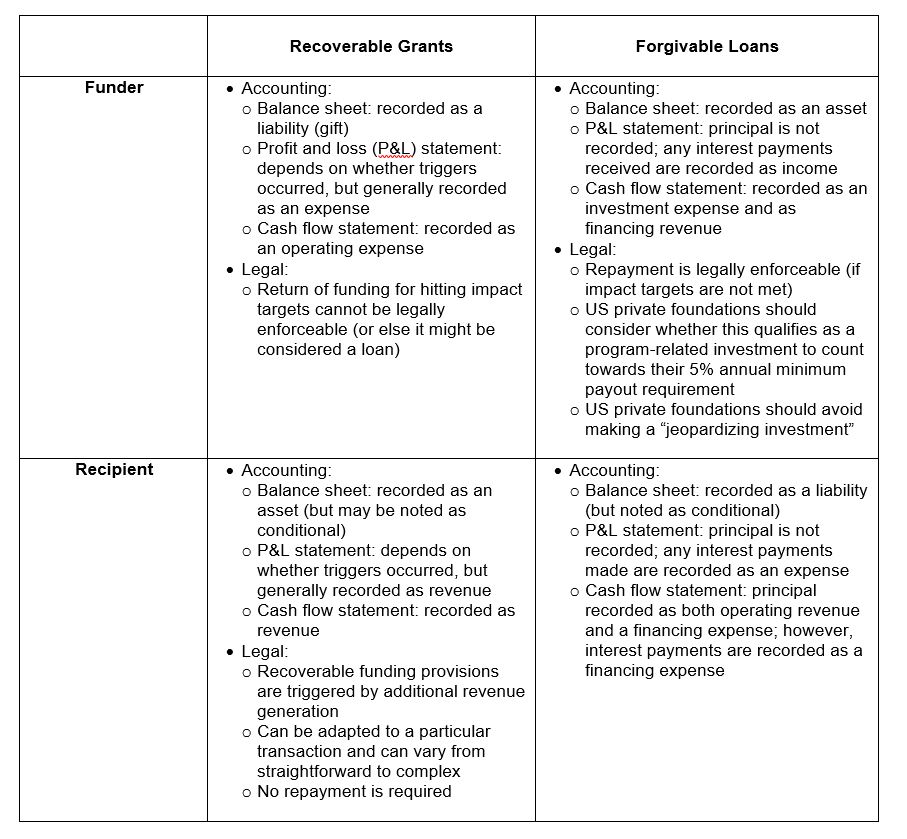

A recoverable grant is not a legally defined term. It is a type of design within a grant in which return of the original grant amount, in whole or part, is tied to the achievement of certain impact targets. It is important that a recoverable grant is not structured (or even referred to) as a repayable grant. If a grantor requires that any portion of its grant must be repaid, there is a risk that the grant will be considered a loan. This may have negative implications from an accounting and legal perspective, as detailed in the table below, for both funders and recipients. This is especially true for US private foundations intending to provide a grant instead of a program-related investment. But where is the line, and how can you mitigate risk in the drafting of your grant agreement? And why might that matter to you as a funder or a recipient?

IN DEPTH

Why and How Are Recoverable Grants Used?

From a programmatic perspective, using recoverable grants can be an effective way to promote sustainable funding and drive accountability for impact. Many donor-advised funds, for example, use recoverable grants in response to increasing donor demand to leverage their contributions. In this way, recoverable grants are typically used as a form of bridge funding. Bridge funding involves providing grant funding to a recipient that needs upfront working capital that may lead to additional sources of funding—for example, start-up social enterprises seeking to raise future debt or equity financing. If a start-up social enterprise is successful in raising future sources of funding, the initial grantor may request that its original grant amount be used for a new purpose. For example, the start-up could use it for a new activity or even provide a new grant to a different social enterprise, thus recycling the original grant amount. In this case, what makes the grant “recoverable” is that the funder does not receive any funds back directly.

Recoverable grants can also be used in a social or development impact bond structure where two different types of funders are involved: an upfront funder and an outcome funder. An upfront funder could provide a recoverable grant to a service provider to implement an activity. If results are achieved, an outcome funder then repays the upfront funder. This makes the original grant “recoverable” instead of repayable because the service provider is not required to pay back the upfront funder. An outcome funder would not provide a recoverable grant to an upfront funder because payment is made only upon achieving results. But an outcome funder might provide a recoverable grant if an outcome fund structure was involved where multiple outcome funders pooled their funding upfront. In this way, if results are not achieved, then the outcome funders’ grant capital can be recycled for other impact bonds. Impact bonds or performance-based structures, such as the Utkrisht Health Impact Bond, Educate Girls Impact Bond and the Educate India Impact Bonds, are great examples where such structures have worked well.

How Do Recoverable Grants Differ from Forgivable Loans?

More recently and particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, forgivable loans such as those provided by the US Small Business Administration under the Paycheck Protection Program have also been seen as an effective way to incentivize employee retention and create a positive impact. A forgivable loan is a form of a loan where the recipient takes on a debt obligation, but upon hitting certain positive impact targets, it does not have to pay back principal and/or interest. Thus, forgivable loans could be structured like an inverse pay-for-results approach where the recipient of a forgivable loan forgoes paying back money it owes instead of receiving payments upon hitting targets. Forgivable loans might be used in situations where lending is common to fund things such as higher education or working capital for small businesses. For the recipient, especially a start-up entity, forgivable loans can also be an easy way to build up positive credit history.

Recently, forgivable loans have been used in the United States in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Paycheck Protection Program, established under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, created a new loan product that provides forgivable loans to small businesses adversely affected by COVID-19. The loans incentivize businesses to retain employees and avoid cutting salaries. Other organizations are also actively raising debt financing and recoverable grant capital to address the healthcare and economic challenges arising from this pandemic.

Whether a recoverable grant or a forgivable loan is used will depend on a variety of factors, including whether the funder is authorized (by law or internal policy) to provide grants or loans, and whether the recipient can or wants to take on debt. For example, some government funders may not have the authority to provide grants or loans, and some recipient organizations may have an internal policy to not take on debt financing. It is even possible to use a hybrid approach by using recoverable grants to fund forgivable loans. If impact targets are hit, then the loan is forgiven and the grant funding does not have to be recovered.

Accounting and Legal Considerations

The chart below sets forth some additional accounting and legal considerations from the funder’s and recipient’s perspectives

Further, if the return of capital in a recoverable grant is not legally enforceable, consider how the funder might still promote accountability. One approach could be to tranche payments instead of making a full payment upfront. This enables the funder to withhold future payments if the recipient does not hold up its end of the bargain. Pragmatically, recipients will likely be concerned about any reputational harm and the effects it may have on their future funding opportunities, especially within the relatively small world of impact investing.

Ultimately, recoverable grants can be a creative way to leverage limited philanthropic funding. Care should be taken in how they are structured and even communicated (avoid using the term “repayable”) so that a funder’s good intentions do not yield unintended consequences.

Jonathan Ng contributed to this article. Jonathan Ng is an attorney advisor for the U.S. Agency for International Development and adjunct faculty member at Georgetown Law. He also co-leads the D.C. chapter of the Impact Investing Legal Working Group.”

/>i

/>i