INTRODUCTION

The significant majority of countries constituting the 131 member Inclusive Framework (“IF”) on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (“BEPS”) have agreed on the broad construct for a deal for Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals (“Agreement”).[1] The key features of the Agreement with respect to Pillar One are set out below, which are more favourable to developing countries when compared with the G7 announcement or the US IF proposal (defined below).

However, several crucial features of the US and G7 proposals also seem to have been accepted such as applying the proposal to all companies and not just digital companies. Before we analyse the impact of these proposals, we set out first how we got here.

Genesis

The tax challenges of the digitalisation of the economy were identified as one of the main areas of focus of the OECD / G20 BEPS Project, leading to the 2015 BEPS Action 1 Report (“Action 1 Report”).[2] The Action 1 Report found that the whole economy was digitalising and, as a result, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to ring-fence the digital economy. Continuing the work of Action 1 Report, the G20 formed a Task Force for Digitalized Economy (“TFDE”) which delivered an Interim Report in 2018 identifying three characteristics of digitized businesses: (i) scales without mass, (ii) heavy reliance on intangible assets, and (iii) data and user participation, as being the main challenges to the existing legal framework.[3] This was followed by the OECD / G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS agreeing on a Programme of Work[4] for addressing the tax challenges of the digitalisation of the economy and arriving on a consensus-based solution by 2020. The Programme of Work is divided into two pillars:

Pillar One addresses the allocation of taxing rights between jurisdictions and considers various proposals for new profit allocation and nexus rules;

Pillar Two focuses on the remaining BEPS issues and seeks to develop rules that would provide jurisdictions with a right to "tax back" where other jurisdictions have not exercised their primary taxing rights or the payment is otherwise subject to low levels of effective taxation.

The OECD / G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPs had released a package consisting of the Reports on the Blueprints of Pillar One[5] and Pillar Two[6] (“Blueprints”), which reflected convergent views on key policy features, principles and parameters of both Pillars, and identified remaining political and technical issues where differences of views remain to be bridged. While the cover statement of the Blueprints provided that participants have agreed to swiftly address the remaining issues with a view to bringing the process to a successful conclusion by mid-2021, the pandemic had stalled the discussions at the global level. In addition to the Blueprints, the OECD also released an economic analysis and impact assessment report (“Impact Assessment Report”) which analyses the economic and tax revenue implications of the Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals.[7]

Simultaneously, the UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters (“UN Committee”) released alternative proposal for introduction of a new Article 12B to tax income from Automated Digital Services (“ADS”)[8] in the United Nations Model Tax Convention (“UNMC”) for the taxation of digital economy.

Meanwhile, in the absence of global consensus, countries resorted to adopt independent unilateral measures through digital services tax (“DST”), and equalization levy’s (“EL”) to tax digital businesses participating in their economies which do not meet the current physical nexus requirements. In response to these unilateral measures, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (“USTR”) initiated investigations under Section 3019 of the Trade Act of 1974 (“Section 301 Investigation”), against DST’s imposed by 9 countries, including India. The Section 301 Investigation involved determination of whether the act, policy, or practice i.e., India’s DST – is actionable under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 (“Trade Act”), and if so, what action, if any, to take under Section 301. On January 6, 2021, USTR released the Section 301 Investigation Report on India’s Digital Services Tax (“USTR Report”), concluding that the EL on-e-commerce operators is ‘actionable’ under the Trade Act. Importantly, the USTR Report stated that the United States remains actively engaged in the OECD Inclusive Framework process and supports bringing the negotiations to a successful conclusion. The USTR Report stated that unilateral laws like India’s DST undermine progress in the OECD by making an agreement on a multilateral approach to digital taxation less likely. Pursuant to the finding in the USTR Report, the USTR proposed to impose retaliatory additional tariffs of up to 25% ad valorem on an aggregate level of trade for certain specific products.[10] The aim of such retaliatory tariff was to neutralize the impact which India’s EL is expected to have on U.S. companies.

Recently, the U.S. Department of the Treasury USA announced the Made in America Tax Plan (“Tax Plan”) with the objective to make American companies and workers more competitive by eliminating incentives to offshore investment, substantially reducing profit shifting and countering tax competition on corporate rates.[11] In addition to the Tax Plan proposals, the presentation by the US to the Steering Group of the Inclusive Framework meeting was leaked (“US IF proposals”).[12]

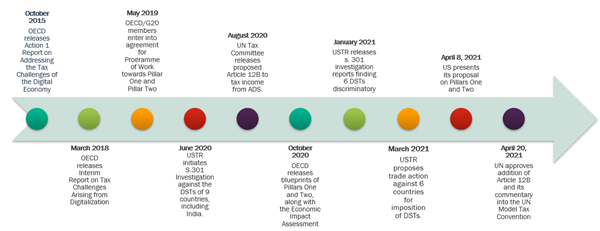

The announcement of the Tax Plan and the US IF proposals re-ignited the global discussions on digital taxation and brought back hope regarding countries arriving at a consensus-based solution for digital taxation. A snapshot of the timeline on international development on digital taxation is provided below:

Digital Taxation in India

India has incorporated several OECD recommendations arising from the BEPS project under the ITA, being an active member of G20 and a Key Partner of the OECD. While several proposals on digital taxation were being discussed internationally, India took an opposing approach by expanding the scope of EL by the Finance Act, 2020 to apply EL at rate of 2% on consideration received or receivable by non-resident e-commerce operators for e-commerce supply or services to specified persons (“E-commerce EL”). The Finance Act, 2021 amended the E-commerce EL provisions and further expanded the scope of the E-commerce EL. Notably, the E-commerce EL applies on transactions between non-residents targeting Indian customers as well. Further, given that the ITA specifically exempts income subject to E-commerce EL from income-tax and that the collection and recovery mechanism of E-commerce EL rely on the provisions of ITA, theoretical arguments exist that E-commerce EL may be considered as ‘taxes covered’ under Article 2 of the tax treaties and hence, treaty benefits may be obtained. However, this position remains untested in India. In the event E-commerce EL is not covered under the tax treaties, there exists a risk of double taxation.

In 2018, India introduced the concept of “significant economic presence” (“SEP”) under the Income Tax Act, 1961 (”ITA”)[13], in order to bring under its ambit the income derived by non-resident businesses, through certain activities in India, who were otherwise without a taxable presence. Since then the SEP provisions have not been operative in absence of the thresholds of the specified activities. Recently, India also announced the SEP thresholds and accordingly, the SEP provisions are now applicable from April 1, 2021.

A snapshot of the timeline on development on digital taxation in India is provided below:

Summary of the Agreement

I. Pillar One Proposal

Scope: Multinational enterprises (“MNEs”) with global revenue more than 20 billion euros and profitability rate greater than 10% would be considered in-scope. The global revenue threshold would be reduced to 10 billion euros going forward. Extractive and financial service sector have been carved out from the scope of Pillar One. The previous notion of covering only automated digital services (“ADS”) and consumer facing businesses (“CFB”) has been done away with.

Nexus: Nexus will be established by the revenue derived by an in-scope MNE from a jurisdiction. In general, 1 million euros revenue from a jurisdiction has been agreed threshold for establishing nexus, for smaller jurisdictions (GDP below 40 billion euros) the revenue threshold has been reduced to 250,000 euros.

Quantum: 20-30% of the profits exceeding 10% margin threshold will be available for redistribution within market jurisdictions. The G7 Agreement in June, 2021 specified rate of at least 20% for residual profits, hence the current Agreement reflects the intent of increasing distributions in favour of market jurisdictions.

Revenue Sourcing: Revenue will be sourced to the end market jurisdiction i.e. where goods or services are used or consumed. However, the exact rules to determine where the usage or consumption has occurred are yet to be determined. MNEs will also be given liberty to choose a reliable method based on their specific facts and circumstances. This is different from the October 2020 blueprint which provided a hierarchy of rules for each revenue stream to be followed by all in-scope companies.

Segmentation: The Agreement provides that segmentation will be undertaken only in exceptional circumstances to include segments of MNEs qualifying under the scope rules basis disclosure in financial statements. This will be relevant for situations wherein the MNE group as a whole does not (primarily due to profit margins) qualify under the scope rules.

Tax Base: This will be determined on basis of financial accounting income (with few adjustments) and provision for carry forward of losses will also be present.

Marketing and Distribution Profits Safe Harbour: In case profits of an MNE are already taxed in a market jurisdiction, then the Amount A liability will be capped to that extent. However, design of the safe harbour is yet to be finalised.

Tax Certainty: Disputes relating to all issues concerning Amount A will be resolved in a mandatory and binding manner. An elective mechanism will be provided to developing countries based on certain agreed criteria.

Administration: All compliances are proposed to be completed through one entity

Unilateral Measures: Digital Service Taxes and other relevant similar measures, such as the Equalisation levy, would be phased out with the application of new rules.

Implementation: The Pillar One proposal would be implemented through a multilateral instrument and the Amount A will come into effect in 2023.

II. Pillar Two Proposal

A quick recap of the different rules under Pillar Two is set out above.

It is not mandatory for the IF members to apply Global anti-Base Erosion (“GloBE”) rules i.e. income inclusion rule (“IIR”) and undertaxed payment rule (“UTPR”). However, if an IF member applies GloBE rules it would need to be consistent with model rules and guidance, and it should also accept GloBE rules applied by other members including the rule order and application of any agreed safe harbours.

MNEs with revenue over 750 million euros would be covered within scope of Pillar Two. However, a jurisdiction in which an MNE is headquartered may apply the IIR even if revenue threshold is not met.

GloBE rules will be applicable on a jurisdictional basis and tax base will be determined according to financial accounting income (with agreed adjustments). Top up taxes will not be imposed if the earnings are distributed within 3-4 years and are taxed at or above the minimum rates.

The minimum rate for the purpose of GloBE rule will be at least 15%.

A formulaic substance based carve out will exclude amount of income that is at least 5% of the carrying value of tangible assets and payroll. There will also be a de minimis threshold for applicability of GloBE rules.

Consideration will be given to the conditions under which US global intangible low-taxed income (“GILTI”) regime will exist with GloBE rules.

Subject to tax rule (“STTR”) will provide a taxing right on the difference of minimum rate and tax rate of payment relating to interest, royalties and a defined set of other payments. Minimum rate for the purpose of STTR will be from 7.5% to 9%.

Implementation plan would include:

GloBE model rules to be developed for facilitating the rules that have been implemented by IF members, including a possibility for introducing a multilateral instrument.

STTR would be implemented through amendments in bilateral treaties. A model STTR provision along with multilateral instrument will be introduced.

There will be some transitional rules, which will include possibility of a deferred implementation of the UTPR.

The implementation plan for Pillar Two will be brought into law in 2022 and will be effective from 2023. Possibility for exclusion of MNEs which are in initial phase of international activity, from scope of Pillar Two will also be explored.

The Agreement reflects consensus on broad framework on the two Pillars. The implementation plan and open issues are to be finalised by October, 2021. A G20 Finance Ministers meet is also scheduled on July 9 – 10, 2021, where we could witness some more developments.

Advantages of the Agreement

The success of Pillar One proposal hinges on international consensus and the amount of tax revenue ultimately being allocated to market jurisdictions like India. It is clear that the original Pillar One proposals were complex, both for the tax administration and multinational companies, and the implications under Pillar One would differ with different business models.

While the Trump administration favoured a safe harbour approach for Pillar One and pushed for grandfathering for Pillar Two, the Biden administration has decided to re-engage with OECD with a view to reaching a global solution. The engagement of the United States has been a major factor leading to the Agreement. However certain recent actions by India, such as imposing SEP or expanding the EL, seemed to be increasing the divide instead of bridging the gap, thereby, threatening the fragile hope for a consensus-based solution. Nevertheless, recent statements by Indian Government show support for the Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals perhaps indicate a willingness to make the deal work.

The complexity associated with the Pillar One proposals was identified by the OECD as one of the key technical issue for Pillar One. Therefore, to this extent, the Agreement supports simplification through a neutral scope definition based on objective factors without regard to business model being digital or otherwise. With increasing digitalization of all business models, this is more likely to create a stable international tax framework which can survive for the long term even as business models undergo greater digital change. This is also in line with the principles agreed in the Ottawa Electronic Commerce: Taxation Framework being, neutrality, efficiency, certainty and simplicity. The Agreement seems to resonate this and focuses towards a sector neutral tax policy.

The next issue is with respect to administrability of Pillar One. In order for developing countries to actually benefit from Pillar One proposal, the revenue allocation should outweigh the administrative costs. The Pillar One Blueprint prescribed threshold of EUR 750 million (which would be reduced in a phased manner in future) for application of Amount A. The Pillar One Blueprint provides that approximately 2,300 MNEs with primary activity in ADS or CFB would be in-scope after application of the global revenue threshold of EUR 750 million. Also, economic impact studies show that using a smaller number will not dramatically increase the amount of revenues from the Amount A taxing right[14]. In this regard, the Agreement has suggested a threshold of EUR 20 Billion, that targets only the ‘largest and most profitable MNE groups’, regardless of industry classification / business model, within the scope of Pillar One.

The Agreement clarifies that segmentation will occur only in exceptional circumstances which would also result in a neutral, simpler, proposal that would also entail lesser compliance costs for taxpayers.

The Agreement provides that Pillar One would be operational through a multilateral instrument which will be developed an opened for signature in 2022. Although many countries have committed to reaching a solution, certain newly introduced features, such as mandatory dispute resolution, might affect the support from some developing countries, which have voiced concerns against such non-optional mechanisms in the past. Any feature that may seem like an infringement of a country’s sovereignty would make the political negotiations surrounding Pillar One contentious. The Agreement has however sweetened the deal by proposing that if Pillar One is successfully implemented then the threshold for Pillar One applicability would come down to EUR 10 Billion after 7 years.

Is the Agreement beneficial for developing countries?

At the outset, the Agreement is a high level document and it may be too early to conclude that the Agreement would be harmful to developing countries like India. While concerns have been raised regarding whether the Agreement may result in a reduction of taxes towards developing countries, it appears such fears are based on assumptions at this point given the fine print may not be available for those proposals. Open points such as profit allocation ratios and negotiations around nexus thresholds would have a significant impact on the final tax position of developing countries under Pillar One. Thereby, the trade-off between a reduced pool available for distribution compared to other benefits from a simplified proposal should be assessed while arriving at a decision.

There are obvious benefits to reducing the total number of companies that are covered from an administrability and simplification perspective as stated above. Further, the Agreement to cover all profitable companies irrespective of the level of digitalization in their current business models would also be aligned with tax policy principles with respect to neutrality. This effect is achieved while also ensuring that the profitable tech companies fall within its coverage. Therefore, any negative assessment of the proposal at this stage based on publicly available information may be premature and based on assumptions. The focus should indeed be on the long term and not be focused on taxing companies that are perceived to have escaped taxation

Future of EL provisions

The Agreement provides that implementation of Pillar One proposals must include a commitment from members of IF to withdraw Digital Service Taxes and not adopt such measures in the future. However, it is unclear whether removal of unilateral measures i.e. E-commerce EL would be possible from the Indian perspective. This may be because the (i) Pillar One Blueprint reaffirms the current international political position of the Inclusive Framework, which has not reached consensus on key design and threshold issues; (ii) It suggests to implement a mandatory dispute resolution framework which goes against Indian tax policy, and is unlikely to be accepted; (iii) As per the Impact Assessment Report, the specific impact of the OECD Proposal on revenue gains within the Indian economy remains unclear.[15] As per media reports, the EL alone has generated more revenue in the last year (~USD 124 million in FY 2018-19)[16], than is presumed to come in through the new Pillar One framework. However, with the Agreement stating the upto 30% of residual profits may be allocated to market countries, it is inching closer to India’s demands. However, India has also made it clear that the intent is to collect more taxes through Pillar One compared to EL, in which case not only 30% of profits must be allocated but also that the 30% is to be calculated based on the total profits and not just residual profits over a 10% profit margin. Therefore, it may be reasonable to assume that the EL will remain intact for the near future.

Why UN proposal does not work

At the outset it must be noted that the proposed changes by the UN Committee are amendments to the existing bilateral treaty framework, and do not suggest a multilateral instrument to resolve issues involving more than two jurisdictions. This implies that the UNMC would be incapable of covering multijurisdictional situations of profit allocation of the global revenue of multinational enterprises across multiple market jurisdictions. For example, the UN proposals does not allocate / recognize value created through exchange of date on multisided business platforms.[17] To the contrary, Pillar One recognizes and taxes this as a value creating function. From a technical perspective, it does not cover all the transactions that the EL currently covers and as a practical matter implementing it is not a short or medium or long term solution.

The UN Committee comprised 25 members from various states, all working in their personal capacity. Among the members who were on the drafting committee, a significant minority dissented on various aspects of the Article. Compared to this, representatives from 139 countries are working on the OECD Pillar One and Two. The OECD also has greater technical capacity due to the number of personnel working with the Inclusive Framework. It is unlikely that these countries, which are committed to a multilateral framework, would instead go through tedious bilateral negotiations with various states, to implement an article which does not guarantee the removal of unilateral taxes such as the EL.

Is global agreement on minimum tax possible?

As mentioned above, Pillar Two proposal was the OECD’s plan to plug remaining BEPS issues and develop rules to provide jurisdictions the right to “tax back” where other jurisdictions have not exercised their primary taxing right, or the payment is otherwise subject to low levels of effective taxation. One of the main objectives is to ensure that the decision to be based in a country is made by companies for non-tax reasons.

India seems to be principally aligned with the Pillar Two proposals and may benefit with respect to offshore structures of Indian companies where their offshore income may become subject to Indian taxes. Revenue from such operations are not always repatriated back into India and retained offshore for further expansion or other business purposes. Tax advantages in the form or a 17% headline rate (in Singapore for instance) and an even lesser effective tax rate acts as an incentive for such structures due to which taxes on such incomes are not paid in India. Therefore, any global minimum tax has the potential to neutralize the tax benefit and countries may then have to compete based factors other than a tax advantage such as better or stable regulatory regime, ease of doing business or access to global talent or resources amongst others.

The US had earlier suggested 21% as the global minimum effective tax rate, but on receiving backlash from several countries, the US has now reduced this rate to 15%. While this should increase the chances of reaching a global agreement, given that US has increased domestic corporate tax rate, it will be crucial to see whether the 15% minimum tax rate is able to secure Congress support. Presumably, the remaining obstacle for arriving a consensus is the around the remaining aspects around Pillar One.

What Next?

In the above context, it is clear that India is likely to push for wide application of the proposals. They had reportedly pushed for a Euro 1 Billion threshold that was intended to cover 5000 companies as opposed to 100. This was also done keeping in mind the interest of Indian companies such as TCS and Infosys. India is also reported to be in talks with other developing countries to secure a better deal and will want to ensure that they collect more money through Pillar I than currently collected by EL (INR 4000 crore since inception and INR 2057 crore in FY 2020-21). Towards that end India will push for a 30% allocation of the entire profits (as opposed to the residual profits that countries are agreeing to tax currently, which is profits over and above the 10% profit margin). Therefore, while India has committed to this deal, it is conditional and not a certainty that they will implement this. The chances of success have significantly increased and focus appears to be in the right direction at present.

The revenue sourcing rules are yet to be finalised. Prescriptive nature of the rules may still cause issues. However, there appears to be some acknowledgement of the fact that they need to be applied by MNCs through a reliable method in the Agreement. This is a significant compliance issue and further details are required to evaluate this. Impact on Indian companies also becomes a key concern with the widening of the scope of the Agreement.

The UTPR rule allocates income to countries such as India from where the payments are made. There is a debate ongoing as to whether the IIR (which allocates income to countries where the companies are resident such as the US) or UTPR should be given the priority in the order of application. This appears to be an open point which India is likely to push for. Overall impact for MNCs should be minimal since this issue is in relation to allocation of taxes and should not increase the overall tax liability. Compliance issues, if any, could arise depending on the implementation of the final proposal under Indian law.

Eight countries have not agreed to this (Barbados, Estonia, Hungary, Ireland, Kenya, Nigeria and Sri Lanka) and others are also asking for more carve outs and exceptions. This may also have an impact on the stability of the deal.

Some of these proposals may have challenges in being accepted by the US Congress. This could also significantly impact the future of the deal.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that taxation of digital economy is in one of the prime concerns within the international tax community. While both the OECD and UN have made their recommendations, the future of digital taxation vests on political agreements and international consensus. Without fixing the structural issues, threshold problems, and allocation of a larger part of the tax base to low/mid income economies, it is unlikely, that states will do away with unilateral measures. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the need for revenues for governments across the world. Unsurprisingly, not only there is a pressing need to bolster tax revenue, the digital economy offers an attractive source for deriving such revenue. Having said this, unilateral measures are facing heightened political tensions across the world with Section 301 Investigation giving rise to trade war like situations. While unilateral measures may have a disproportionately negative effect on high-investment, low-margin businesses, along with creating the possibility of the additional cost being passed down to customers, from an Indian perspective, as discussed above, the EL is likely to be presumed to remain for now.

Against the backdrop of the pandemic and struggling economies, it is hoped that importance or rather necessity of encouraging trade and economic activity is prioritised over a disagreement regarding tax allocations. A tax related trade war or a further entrenchment of unilateral levies is likely to further harm both the global and national economies, including consumers. A less than ideal deal may still appear to be better than the next best alternative.

1 OECD (2021), OECD Secretary-General Tax Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors – July 2021, OECD, Paris.

2 OECD (2015), Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy, Action 1 - 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris.

3 OECD (2018), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris.

4 OECD (2019), Programme of Work to Develop a Consensus Solution to the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD, Paris.

5 OECD (2020), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar One Blueprint: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris.

6 OECD (2020), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar One Blueprint: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris.

7 OECD (2020), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Economic Impact Assessment: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Paris.

8 UN Committee of Experts on International Tax Cooperation in Tax Matters (2020), 20th Session, Tax Consequences of the Digitalised Economy-issues of relevance for Developing Countries, Co-Coordinator’s Report, E/C.18/202/CRP.41

9 Section 301 of the Trade Act sets out three types of acts, policies, or practices of a foreign country that are actionable: (i) trade agreement violations; (ii) acts, policies or practices that are unjustifiable (defined as those that are inconsistent with U.S. international legal rights) and burden or restrict U.S. Commerce; and (iii) acts, policies or practices that are unreasonable or discriminatory and burden or restrict U.S. Commerce.

10 Proposed Action in Section 301 Investigation of India’s Digital Services Tax, March 31, 2021

11 Made in America Tax Plan Report. Available here.

12 Martin, Julia. (2021, April 12). Leaked copy of US proposal for Pillar One and Two multinational group tax reforms available. MNE Tax.

13 Explanation 2A to Section 9(1)(i).

14 See here.

15 The global revenue growth estimated from Pilar One and Pillar Two both, is approximately 50-80 billion USD (4% of global corporate income-tax revenue). However, the tax revenue gain experienced by most economies from the Pillar One reallocation will be a relatively small portion of the overall predicted gain, with ‘investment hubs’ experiencing a substantial loss in tax revenues. Majority of the tax revenue gains of the estimated over all 4% increase would thus be from Pillar Two, which proposes a minimum tax rate (giving countries the right to tax back profit of the global multinational enterprise that is taxed below the minimum rate elsewhere). Revenues from the proposed minimum tax under Pillar Two is disproportionately higher in high income economies, as opposed to a minimal increase in low/middle income countries. Pillar Two will also lead to increased revenue gains from reduced profit shifting, the impact of which is largely similar for most economies. [OECD 2020, Webcast Presentation, Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalization of the Economy- Update on the Economic Analysis and Impact Assessment, 13.02.20]

16 See here.

17 For example, multi-sided markets such as Google and Facebook. In these models, one side of the market exchange is between the entity and the user, which is for a free service (social media, search engine) in exchange for user data collected through the process. This data is then processed and exchanged for monetary consideration to the other side of the market as targeted advertisement for businesses, thus generating monetary

/>i

/>i