The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report on February 23, 2023, entitled “EPA Chemical Reviews: Workforce Planning Gaps Contributed to Missed Deadlines.” GAO evaluated the extent to which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) met selected Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) deadlines for reviewing existing and new chemicals since June 2016, and to which EPA engaged in workforce planning for implementing its chemical review responsibilities. GAO identified five principles with which federal agencies’ strategic workforce planning efforts should align. According to the report, while EPA officials agree that the principles are “relevant and reasonable for its TSCA workforce planning efforts,” they have not yet developed a process or timeline to align fully such efforts with these principles.

Why GAO Did the Study

On June 22, 2016, former President Barack Obama signed the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act (Lautenberg) into law. The report notes that its TSCA amendments included establishing new deadlines for reviewing chemicals already in commerce, including an initial set of ten existing chemicals, and requiring that EPA make a formal determination before new chemicals can be manufactured. The Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce asked GAO to review EPA’s implementation of its chemical review responsibilities under TSCA. According to the report, GAO reviewed relevant laws, regulations, and workforce planning documents and collected EPA data on new chemical review times and its workforce. GAO also interviewed EPA officials and representatives from industry and environmental health stakeholder organizations.

What GAO Found

The report states that since 2016, EPA “has missed most deadlines” for reviewing existing and new chemicals under TSCA, as amended. After EPA prioritizes existing chemicals, it reviews them in two main phases -- risk evaluation and risk management -- and TSCA established specific deadlines for each phase. According to the report, GAO found that EPA completed the first risk evaluation step (i.e., scoping) for the initial ten existing chemical reviews on time. EPA “missed all but one” of the subsequent risk evaluation and risk management deadlines for these chemicals, however.

Additionally, TSCA as amended provides that a person may manufacture a new chemical only after submitting a premanufacture notice (PMN) to EPA and EPA making an affirmative determination on the risk of injury to health or the environment. According to the report, GAO found that among the PMN reviews that EPA completed from 2017 through 2022, “the agency typically completed the reviews within the 90-day TSCA review period less than 10 percent of the time.” The report states that EPA missed the chemical review deadlines due in part to several contributing factors and is implementing some related improvements (e.g., modernizing information systems). The report notes that according to EPA, resource constraints, including insufficient staff capacity, remain the primary reason for missed chemical review deadlines, however.

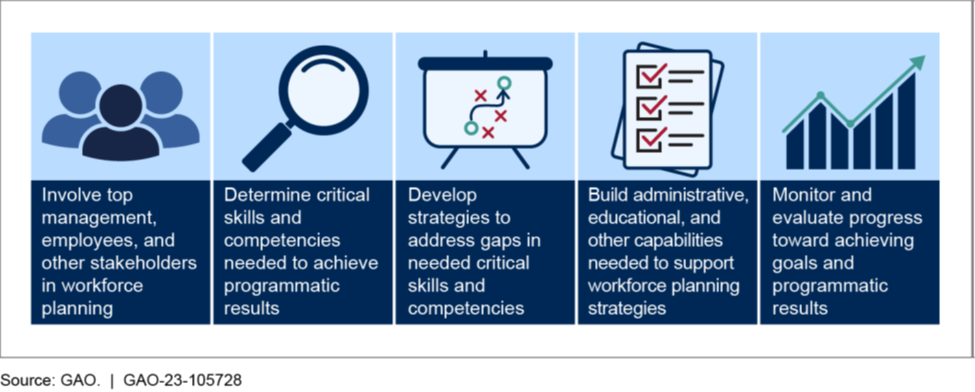

The report states that although EPA has engaged in some initial workforce planning activities for its chemical review responsibilities, significant workforce planning gaps contributed to missed chemical review deadlines. For example, according to the report, in March 2021, EPA conducted a skills gap assessment that included hiring targets for mission-critical occupations. EPA officials told GAO that the assessment no longer reflects current workforce needs, however, and that EPA has not created a strategic workforce plan to develop long-term strategies for recruiting, developing, and retaining staff. GAO identified the following five principles with which federal agencies’ strategic workforce planning efforts should align:

According to the report, “EPA officials told GAO that while they agree that these principles are relevant and reasonable for its TSCA workforce planning efforts, they have not developed a process or timeline to fully align such efforts with these principles.” The report states without doing so, “EPA will likely continue to struggle to recruit, develop, and retain the workforce it needs to meet TSCA deadlines for completing existing and new chemical reviews.”

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that EPA develop a process and timeline to align fully its workforce planning efforts for implementing its TSCA chemical review responsibilities with workforce planning principles. The report states that EPA agreed with GAO’s recommendation “but indicated that insufficiency of resources is the primary factor, among others we noted, for missed deadlines.”

Commentary

We generally agree with GAO that EPA’s Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (OPPT) has done inadequate workforce planning to address critical specialties. This problem, however, predates the Trump Administration and, in fact, predates Lautenberg, which exacerbated the problem. While it may be accurate that the previous Administration did not request adequate resources for OPPT to implement TSCA, this statement neglects to mention that the Obama Administration also did not make such a request. In addition, the Trump Administration routinely requested budgets substantially below what would be required for EPA to function optimally and, every year, Congress passed budgets that kept OPPT funding intact. Congress could have increased funding if it viewed OPPT’s budget as inadequate.

More problematic is that for much of the decade prior to 2016, OPPT’s workplace strategy was to retire two (or three) to hire one. The timing was such that the senior employees had to depart before the new, junior employees were hired, meaning the new employees seldom benefited from the retiring employees. The report also does not address what some would characterize as a challenging work environment in which some OPPT scientists are not comfortable questioning the conclusions of other EPA scientists.

The report mentions, but provides little insight into, inconsistent chemical reviews. As it stands, a chemical may be submitted twice and receive different evaluations. It is difficult to reconcile this fact with the Section 26 mandate to use the “best available science.” There is no doubt that workplace shortages contribute to this problem, but it is also evidence that there is insufficient internal quality control. Our experience suggests that if a submitter identifies errors in one of OPPT’s evaluations, these communications are regarded more as unwelcome industry interferences in OPPT’s work, as opposed to necessary and constructive scientific engagement that is customary to rebut what a submitter regards as EPA error in reviewing the information.

We are also disappointed in how the report characterizes PMN outcomes in Table 2. The report follows OPPT’s characterization as “not likely” determinations with significant new use rules (SNUR) as being “allowed to commercialize without restrictions.” The reason EPA proposed those SNURs was to prohibit potentially problematic conditions of use. EPA seems to want to have it both ways: that a SNUR restricts the use but is also somehow not a regulatory restriction. The report also undercounts the number of cases prohibited from commercialization. While EPA may not have issued any orders imposing an outright ban on a new chemical, EPA ignores the large number of cases that were withdrawn by submitters, whether because the regulatory restrictions are too costly to proceed or for other business reasons. Every withdrawal is a de facto block on the commercialization of that substance. It is likely not the case that all withdrawals are done in the face of bans -- submitters may withdraw for a variety of reasons -- but it is the case that every withdrawal prevents the submitted substance from being commercialized.

We are also disappointed that the report does not address OPPT’s lack of clarity on what it views as not likely to present unreasonable risk under the reasonably foreseen conditions of use. In our view, the interpretation of this phrase is a major problem with how Congress intended the new chemicals program to function. OPPT has yet to clarify how likely “not likely” is. In the past, OPPT had stated that “reasonably foreseen” included intended, known, and reasonably foreseen (but merely hypothetical) conditions of use. That statement has been removed from EPA’s website and work products. Without a definition, how can OPPT assessors and risk managers consistently conclude what meets that standard, and how can submitters know what information is necessary to enable OPPT to make such a determination? We have written extensively on our view that OPPT is taking an impermissible hazard-based approach in its reviews: if a substance exhibits (or potentially exhibits) a hazard other than low hazard, OPPT imposes a restriction. Our view is that interpretation of TSCA does not accurately reflect Congress’s intent and the clear statutory language that requires that OPPT evaluate the potential risk of a substance. Instead, OPPT has rendered meaningless the term “reasonably foreseen” because everything is foreseeable. If EPA’s view is that it must regulate every hazard for every conceivable condition of use, it is not surprising that OPPT is going to be overworked; nearly every chemical necessitates a regulatory action. In 2022, for example, EPA issued orders for 95 percent of PMNs. Nowhere in the GAO analysis does the report question whether OPPT is properly implementing Lautenberg and the distorting effect this has on EPA’s workforce needs. We acknowledge OPPT’s need for additional employees, but OPPT’s throughput issues cannot be addressed by simply hiring more people. Workforce planning is (and has been) a critical problem in OPPT for more than a decade. Planning is vital for the well-functioning of the office, but better workforce planning will only solve part of the problem. Policy changes are urgently needed to implement Lautenberg as Congress intended.

/>i

/>i