Following on Mike Mascia’s Closing Remarks delivered to young Fund Finance professionals at last month’s FFA University 1.0, I wanted to take things back to the basics for those who are just starting their careers in fund finance.

“Do they lend above the fund or below the fund?”

These are the first words that come to mind when I think about the start of my career in fund finance. Like many young professionals before me, I walked into my first interview armed with as much knowledge as I considered feasible to cram into my brain about an area of finance which, up until the moment I was asked that foreign question, I had little understanding.

Multiple articles, flowcharts and PowerPoint presentations later, I began to make advances at installing this new language into Fund Finance Fiona 1.0. As I continued to embark on the next steps in my career, the amount of legal and business jargon I needed to learn grew – but my confidence also grew.

As we welcome this year’s fresh batch of first-year associates, it seems as appropriate a time as any to take things back to basics – because there is nothing like teaching that is as effective to reinforce your own learning. So if this is one of many articles, flowcharts and PowerPoints you have reviewed, or that remain on your horizon, know that in time, the foreign will become the familiar.

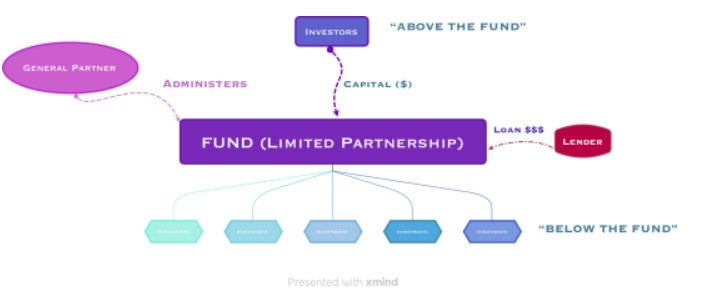

So what is fund finance? What is a fund? What is happening above and below it? What are some key considerations for lenders when structuring, negotiating and documenting such credit facilities?

What Is a Fund?

-

A vehicle for making investments

-

Commonly structured as a limited partnership

-

Made up of investors (limited partners) and administered by the general partner

Investors will subscribe to a fund by signing a subscription agreement and committing to a certain amount (the general partner is then able to accept any commitment amount for the investor up to the total amount offered). A fund may solicit a single investor (a fund of one or separately managed account/SMA) or a variety of investors, and hold multiple closings to bring on additional investors for its investment purposes. Investors are not required to fund all of their commitment upfront, but rather, each investor is contractually bound to fund capital calls from the general partner on behalf of the fund. The general partner will call capital by delivering a notice to its investors, and each such notice (a capital call notice) will state the amount and purpose of the capital call (e.g., an investment, follow-on investment or, importantly from the lender’s lens, the repayment of debt).

Note: investors or limited partners are not involved in the management of the fund and have limited liability, typically restricted on the basis of the aggregate value of their capital commitment.

What Is Fund Finance?

“A revolving credit facility is just like a credit card for a fund!”

The best starting point to learn something new is to build its foundation relative to concepts you already know and understand. So why are we comparing a typical fund finance transaction to a credit card?

The types of loans we generally deal with in the world of subscription lending (see below) are revolving credit facilities. This means that a borrower is able to, during the life of the loan, borrow, repay and borrow again – similar to the same way a retail consumer would use a credit card, but with one caveat: the loans typically have a term of two to three years (with possibly an extension) and which may include mechanisms for extension either at the borrower’s option or subject to lender approval.

What is happening above and below the fund: an intro to subscription lending, NAV and hybrid facilities.

There are two overarching types of facilities in fund finance – subscription credit facilities and net asset value (NAV) facilities. With respect to a subscription credit facility, the lender looks to the uncalled capital commitments of the investors of the fund (the amount the investor committed to the fund that hasn’t been subject to a capital call) and the security package includes the capital call rights of the general partner (who, as you may recall, administers the fund and makes capital calls to the investors by delivering capital call notices) and the account(s) into which capital calls are funded. NAV facilities, on the other hand, are secured by the assets or actual investments held by the fund or the equity interests in the vehicles that hold such investments.

As demonstrated above, subscription facilities look to the uncalled capital commitments of the investors (i.e., above the fund) and NAV facilities look to the assets of the fund (i.e., below the fund).

Breaking Down the Role of a Fund Finance Attorney

For the purposes of this article, we will focus on subscription lending facilities.

I. Diligence

LPAs – to bank or not to bank?

Often, before a deal is even mandated, attorneys will be engaged to diligence the limited partnership agreement (LPA) of the prospective borrower. The LPA will set out the obligations of the limited partners, the rights and role of the general partner, and capital call procedures. The terms of the LPA can make the difference between a deal that is bankable and one that’s not! From a lender’s perspective, the fund must be authorized under its LPA to borrow and pledge investor capital commitments, state that investors are obligated to fund capital calls without setoff, counterclaim or defense, and have typical remedies for investor defaults. Among other things, lenders are also interested in the ability to overcall (i.e., to call on other investors to fund capital where there is a shortfall caused by excuse rights or default by other investors).

Side letters – mine is bigger than yours!

As indicated above, investors subscribe to a fund by signing a subscription agreement. But what happens if an investor would like to alter its rights and obligations? Since a subscription agreement is typically a form, any additional rights or obligations will need to be documented separately in a side letter. While certain side letter provisions will be irrelevant in the context of a financing (e.g., negotiated management fees), a lender is interested in anything that will interfere with its ability to get repaid in an event of default – i.e., anything that limits the ability to call capital from the limited partners, such as cease funding or withdrawal rights, overcall limitations, reservation of sovereign immunity, commitment caps and capital call formalities. In addition, lenders are concerned about most favored nations (MFN) provisions, which allow investors to elect the same terms that are available to any other investor with the same (or a smaller) commitment amount. Why? Because as an investor, you want value for your money – if you have committed a certain amount of capital to a fund, wouldn’t you want at least the same rights as anyone else who has committed the same amount? For an overview of common side letter provisions relevant to subscription lenders, see here.

II. Documentation – run before you walk!

The standard loan documents for a subscription credit facility include the credit agreement, security agreements (which may include local and foreign security agreements depending on the jurisdiction of the borrower), collateral account pledges, deposit account control agreements (DACAs), fee letters and other ancillaries. The credit agreement sets out the terms of the facility, including lenders’ obligation to fund, borrowing procedures, interest and repayments, representations and warranties of the borrower and other credit parties, affirmative and negative covenants, conditions precedent to closing, events of default and other mechanics. In the U.S., credit agreements are generally based on the Loan Syndications and Trading Association (LSTA) form, whereas in the UK, credit agreements are generally based on the Legal Marketing Association (LMA) form.

Once the loan documents are signed and signatures released by the parties to the transaction, attorneys are responsible for ensuring that the lender’s security is perfected by (i) control, i.e., the execution of the DACA for any collateral account, and (ii) by filing Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) financing statements with the appropriate filing office in respect of the intangible rights.

III. Structuring and Negotiating

It almost seems counterintuitive that the role of structuring a subscription facility comes later than both diligence and documentation. But in order to structure a product, you must first understand it. What does this mean for anyone that is new to fund finance? Review, review, review. Review the structure chart (which in practice will certainly include more than one fund borrower), review the organizational documents and review the investor documents. Only by understanding the fund structure (including where a borrower sits relative to its related entities) can we begin to provide advice on the building blocks of a transaction. This means understanding where investors are coming in (to which entity investors are subscribed), and tracking the flow of funds to ensure that the loan documents adequately capture the relationship between the various entities, the capital commitments, capital call rights and ancillary rights.

Conclusion – Welcome to the Kiddie Pool!

As Malcom Gladwell discussed in one of his bestsellers, Outliers, to become an expert, it takes approximately 10,000 hours (or approximately 10 years) of deliberate practice. The words I impart upon you today are words I have repeated dozens of times as I welcome new attorneys and bankers alike to the world of fund finance. As to whether it really takes 10,000 hours, only time will tell.

/>i

/>i