Multiemployer benefit plans generally require contributing employers to submit “remittance reports” that identify the employees that performed covered work, the type of work performed, and the amount of time worked. Plans rely on the timely and accurate submission of these reports to ensure employers remit all required contributions and that participants accrue all benefits owed. Most plans will also require contributing employers to submit to periodic audits to identify any discrepancies between the submitted reports and the employer’s records. Even though employers are generally required to maintain accurate records by contract and applicable law, some employers fail to do so. Additionally, records may be destroyed, or employers may refuse to provide them. To address these situations, many plans have adopted rules and procedures permitting them to collect “estimated” contributions, typically by allowing the plan’s auditor to extrapolate from the employer’s past contribution history. In Sheet Metal Workers’ Health & Welfare Fund of N. Carolina v. Stromberg Metal Works, Inc., 118 F.4th 621 (4th Cir. 2024), the Fourth Circuit joined a number of other Circuits that have endorsed this practice, holding that the plan could collect estimated delinquent contributions because the employer’s records made it impossible to determine the precise amount of contributions due for each employee.

Background

Stromberg Metal Works is a commercial sheet metal fabrication and installation company that employs union sheet metal workers. Stromberg signed collective bargaining agreements that require it to pay contributions to various multiemployer benefit plans for health, pension, and other fringe benefits. The amount of contributions depends on each employee’s job classification, with lower contribution rates for non-journeymen (i.e., those with less experience) than journeymen. Pursuant to the CBAs, Stromberg agreed to refer employees to the local union for classification. Stromberg also agreed to a “default” two-to-one staffing ratio of non-journeymen to journeymen and a “modified” four-to-one staffing ratio for two specific projects. In 2017, Stromberg hired temporary sheet metal workers for various projects and did not refer them to the local union for classification; instead, Stromberg remitted contributions to the plans using the lowest contribution rate for non-journeymen. When the plans subsequently initiated an audit, Stromberg failed to provide the plan’s auditor with documentation necessary to determine how much time the employees worked on each project, and because it had failed to refer the employees to the local union, it was unknown how they should have been classified. In the absence of this information, the auditor assumed that the employees were staffed in accordance with the default ratio, and calculated that over $823,000 was owed on account of Stromberg remitting contributions at the lowest contribution rate for non-journeymen.

In the plans’ subsequent collection action, the district court sustained the auditor’s assumptions and entered judgment in favor of the plans for the delinquent contributions and accumulated interest and liquidated damages. The court rejected Stromberg’s arguments that the plans must determine the actual classification for each employee or use the modified staffing ratio instead of the default ratio. The court pointed out that it was Stromberg who had failed to comply with the obligation to refer these employees to the local union for classification and to maintain records necessary to determine which staffing ratio should apply.

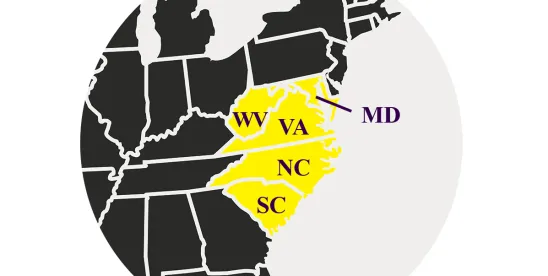

On appeal, the Fourth Circuit affirmed that the plans were entitled to use the default staffing ratio to estimate the amount of delinquent contributions. The Court reasoned that an employer cannot be heard to complain that damages lack exactness when such imprecision is the result of its own failure to keep adequate records. Joining the Sixth, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits, the Court adopted the following burden-shifting framework: once a plan shows that an employer owes delinquent contributions and has failed to maintain pertinent records, “the burden shifts to the employer to prove the precise amount of damages” and, if it cannot, the “fund is entitled to a damages award in an amount approximated as a matter of just and reasonable inference.” Applying that standard, the Court affirmed that Stromberg failed to satisfy its burden to prove the precise amount of contributions owed, and therefore, the auditor’s “estimated” contributions remained unrebutted. Because, however, Stromberg had identified “computational and methodological errors” in the auditor’s work, the Court remanded to the district court to address those errors.

Proskauer’s Perspective

Multiemployer plan trustees have a fiduciary obligation to collect the contributions owed to the plans they oversee, and the Fourth Circuit’s decision is a reminder that an employer’s failure to maintain accurate records is not likely to deter plans from enforcing those obligations. In fact, such a failure may prevent the employer from setting forth the facts necessary to rebut determinations by the plan’s auditor and expose the employer to interest, liquidated damages, and attorneys’ fees and costs incurred by the plan to collect any delinquent contributions.

/>i

/>i