On August 21, 2019, FinCEN issued an advisory (the “Advisory”) alerting financial institutions to various financial schemes and mechanisms employed by fentanyl and synthetic opioid traffickers to facilitate the illegal fentanyl trade and launder its proceeds.

As defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(“CDC”), “fentanyl is a synthetic (man-made) opioid 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent that morphine.” In 2017, more than 28,000 deaths involving fentanyl and other synthetic opioid occurred in the United States. As noted in the Advisory, fentanyl traffics in the United States from two principal sources: from China by U.S. individuals for personal consumption or domestic distribution or from Mexico by transnational criminal organizations (“TCOs”) and other criminal networks. In turn, these trades are funded through a number of mechanisms, including: purchases from a foreign source made using money servICES businesses (“MSBs”), bank transfers or online payment processors; purchases from a foreign source made using convertible virtual currency (“CVC”); purchases from a domestic source made using MSBs, online payment processors, CVC or person-to-person cash sales.

Recognizing fentanyl traffickers’ modus operandi is critical to detecting and preventing these illicit transactions. Thus, the Advisory provides detailed illustrations of each of the above-identified forms of transaction in order to assist financial institutions to detect and prevent facilitating fentanyl trafficking.

Foreign Purchases Using MSBs

From its analysis of financial data, FinCEN concluded that “when U.S. individuals purchase fentanyl directly from China and other foreign countries, they often structure the money transfers to evade Bank secrecy Act (‘BSA’) reporting and recordkeeping requirements.”

In a typical case, a U.S. individual will contact a foreign website selling fentanyl (or other illicit or prescription drugs). The websites, typically registered to or operated by individuals located in China, will direct the purchaser to contact a representative of the company by telephone, text message or email. Once the buyer and sales representative have come together and agreed to the transaction, the sales representative will direct the buyer to send payment to a particular person through an MSB located in the U.S., an online payment processor, or a bank transfer.

Included with this contact information is usually a telephone number, which may be associated with a foreign-based website or otherwise connected to other foreign payment recipients or couriers. Generally, payments to the foreign sources are low-dollar-value transactions, sometimes conducted through multiple transaction or in a single transaction. In some cases, the foreign supplier may direct the purchasing individual to send a bank transfer directly to a front company operating in the chemical manufacturing field or to a shell company. In these cases, payments are higher-value and may be associated with bulk drug or precursor chemical purchases.

Once the financial component of the transaction has concluded, the foreign source will ship the fentanyl directly to its U.S. buyers. The Advisory sets forth this graphic regarding transfers to such foreign-based contacts:

Foreign Purchases Using CVC

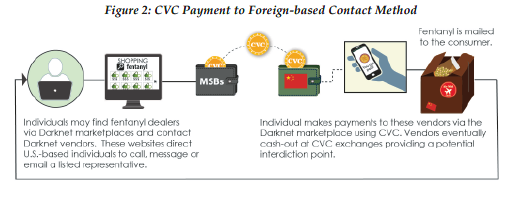

Conducting transactions through the darknet using CVC to complete fentanyl purchases is an increasingly common practice among fentanyl traffickers. FinCEN has found that “domestic illicit drug manufacturers, dealers, and consumers use online payment platforms or CVC to purchase precursor chemicals or completely synthesized narcotics primarily from China.” In these cases, the purchaser identifies drug sources from anywhere in the world – but, in the case of fentanyl, usually in China – through embedded messages or references on websites that signal illegal drugs availability. Representatives of foreign suppliers will direct the purchaser send payments through CVC and, once the purchaser has done so, will ship the illegal drugs to the consumer. Subsequently, the foreign source will seek to exchange CVC for traditional fiat currency using both domestic and foreign-based CVC exchanges, or, alternatively, will sell the CVC themselves to the public as unlicensed money transmitters, an additional step that further conceals the source of the CVC. The Advisory sets forth this graphic regarding such transfers of CVC:

Cross-Border Trafficking

Mexico is the second primary source of fentanyl trafficked in the United States. Mexican TCOs control the smuggling routes into the U.S. and arrange for transport and distribution throughout the U.S. On the back-end, Mexican TCOs arrange the consolidation, placement, and movement of proceeds of fentanyl sales in the U.S. According to FinCEN, these transactions “involve structured cash deposits, money transfers, and wire transfers for the ultimate credit of accounts in the U.S. SWB (Southwest Border) region and Mexico.” To launder the proceeds of illegal fentanyl sales, Mexican TCOs “conduct excessive cash transactions using ATMs, unsourced cash, and no verifiable or legitimate purpose for the transactions.” Also, “[d]rug trafficking networks often use shell companies to disguise the illicit drug proceeds as legitimate business transactions” or “individuals located in the United States use their accounts to funnel funds between domestic and international locations.”

FinCEN describes some of the most common cross-border laundering practices. In many cases, Mexican TCOs will simply smuggle bulk cash across the California border through privately-owned vehicles or commercial tractor-trailers.

When such bulk cash smuggling is impractical, Mexican TCOs employ less conspicuous alternatives, such as trade-based money laundering schemes. In these schemes, the TCO will use the proceeds of fentanyl sales to purchase goods for export, such as cars, smart phones or jewelry, export those items across the border for resale, thus disguising the proceeds as from legitimate sales.

To facilitate these transactions, a Mexican TCO will transfer funds to an international jurisdiction using either internal accountants or an independent accountant – the “money broker” – with whom it will negotiate a money pick-up and to whom it will pay a commission fee. Either personally or using assistant launderers, the broker will pick up proceeds and deposit it into U.S. financial institutions (usually structured to avoid reporting and record-keeping requirements) and transact from these institutions with vendors and exporters. The vendor who receives the proceeds will export the goods to Mexico where they will be sold on the open market at a mark-up.

Mexican TCOs also may launder drug proceeds through structured MSB money transfers. In these circumstances, TCOs will work with professional money launderers to send money to Mexico via U.S. MSBs structured to evade reporting requirements. The structuring is accomplished in several ways: the proceeds may be divided between multiple individuals who send the transfers; an individual may use multiple MSB agent locations to send transfers; an individual may send multiple transactions consecutively.

Finally, Mexican TCOs employ a funneling mechanism where deposits are made in multiple states geographically distant from the branch where the account was opened and geographically different from the location of the withdrawal activity. The deposits are structured to evade reporting requirements. This final form of laundering has decreased as more large national banks have restricted third-party cash deposits for private customer accounts.

Red Flags to Monitor

The advisory sets forth numerous red flags for MSBs and depository institutions to monitor for in connection with fentanyl proceeds laundering.

For MSBs, those red flags include:

- A money transfer beneficiary lists a phone number or email address associated with a pharmaceutical or medical company;

- A U.S remitter sends money into China for no apparent legitimate purpose;

- Multiple U.S. remitters send money transfers to the same individual beneficiary in China or Mexico;

- Seemingly unrelated beneficiaries share the same phone number or email address;

- The volume of transfer activity is inconsistent with the remitter’s stated purpose;

- Evidence of structuring.

Depository institutions should look out for:

- Evidence of structuring;

- The physical condition of deposited cash is suspicious;

- The source of funds cannot be corroborated;

- Multiple transactions below the currency transaction report threshold.

Depository institutions also should monitor for deposits to shell companies. Evidence that a beneficiary may be a shell company include:

- It has an unclear business model;

- Discrepancy between company address and location;

- Vague or non-descriptive company name not matching stated purpose;

- Multiple or inconsistent employer identification numbers.

Finally, CVC exchangers should carefully monitor the following information sources for evidence of suspicious activity:

- Virtual currency wallet address;

- Account information;

- Transaction details;

- Relevant transaction history;

- Available login information;

- Mobile device information.

The Advisory states that financial institutions filing relevant Suspicious Activity Reports should “reference this advisory using the following key terms in SAR field 2 (Filing Institution Note to FinCEN): ‘FENTANYL FIN-2019-A006.'”

Conclusion

The government is waging its war against the trafficking of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids on multiple fronts. As with other enforcement efforts, any disruption to the financial transaction chain can be a forceful blow to drug traffickers. The Advisory is a thorough reminder that the government regards financial institutions as playing a critical role in these efforts. Although the Advisory is detailed and instructive, the Advisory and its lists of red flags nonetheless will add to the compliance burden of financial institutions, which presumably will be deemed to be on notice of the listed red flags and therefore expected to adjust and enhance their AML monitoring and reporting programs accordingly.

/>i

/>i