In Biogen International GmbH v. Banner Life Sciences LLC, the Federal Circuit construed language of the Hatch-Waxman patent term extension statute in a manner Biogen argued was inconsistent with the “active moiety” focus of its 2004 decision in Pfizer Inc. v. Dr. Reddy’s Labs., Ltd. The court distinguished Pfizer—perhaps incorrectly—and based its decision on the statutory definition of “active ingredient.” Having found the accused product to be outside the literal scope of the extended patent rights, the court determined that the doctrine of equivalents was not available.

The Hatch-Waxman Patent Term Extension Statute

The patent term extension provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Act are set forth in 35 USC § 156. The basic extension provision is set forth in § 156(a), which provides:

(a)The term of a patent which claims a product, a method of using a product, or a method of manufacturing a product shall be extended in accordance with this section from the original expiration date of the patent, which shall include any patent term adjustment granted under section 154(b), if— …

(4) the product has been subject to a regulatory review period before its commercial marketing or use ….

The extended rights are set forth in § 156(b), which provides in relevant part that, for a patent which claims a method of using a product, the extended rights are “limited to any use claimed by the patent and approved for the product.”

At issue in this case was the meaning of the term “product,” which § 156(f) defines as a “drug product,” which it in turn defines as the “active ingredient” of a new drug “including any salt or ester of the active ingredient, as a single entity or in combination with another active ingredient.”

The Patent And Accused Product At Issue

The patent at issue was Biogen’s U.S. Patent No. 7,619,001, which is listed in the Orange Book for Biogen’s multiple sclerosis drug Tecfidera®. The active ingredient of Tecfidera® is dimethyl fumarate (DMF). The active ingredient of Banner’s accused product is monomethyl fumarate (MMF) (also called methyl hydrogen fumarate), which is the active metabolite of DMF.

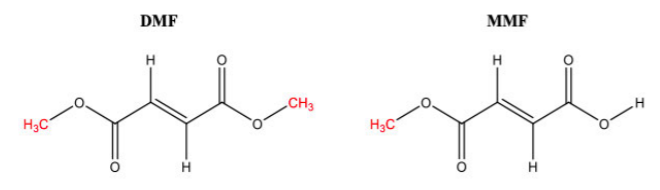

In chemical terms. MMF can be described as a de-esterified form of the double ester DMF. The Federal Circuit opinion depicts their structures as follows:

The court treated claim 1 of the ’001 patent as representative:

- A method of treating multiple sclerosis comprising administering, to a patient in need of treatment for multiple sclerosis, an amount of a pharmaceutical preparation effective for treating multiple sclerosis, the pharmaceutical preparation comprising at least one excipient or at least one carrier or at least one combination thereof; and dimethyl fumarate, methyl hydrogen fumarate, or a combination thereof.

Claim 1 literally encompasses both DMF and MMF.

The Federal Circuit Decision

The Federal Circuit decision was authored by Judge Lourie and joined by Judges Moore and Chen.

The court considered the parties case law-based arguments, but determined that the issue before it “is governed by the statute.” In particular, the court focused on the “active ingredient” definition of “product” in § 156(f), stating:

“Active ingredient” is a term of art, defined by the FDA as “any component that is intended to furnish pharmacological activity or other direct effect,” 21 C.F.R. § 210.3(b)(7), and it “must be present in the drug product when administered.” Hoechst-Roussel Pharm., Inc. v. Lehman, 109 F.3d 756, 759 n.3 (Fed. Cir. 1997) (citation omitted). The active ingredient of a given drug product is defined by what is approved and is specified on the drug’s label.

As noted above, § 156(f) defines “drug product” as “including any salt or ester of the active ingredient.” Applying these definitions to the facts before it, the court stated:

MMF is not the approved product, nor is it specified as the active ingredient on the Tecfidera® label. …. MMF is the de-esterified form of DMF, not an ester of DMF.

Thus, the court reasoned, Biogen’s extended patent rights based on FDA approval of DMF do not reach MMF, because:

[T]he term “product,” defined in § 156(f) as the “active ingredient . . . including any salt or ester of the active ingredient,” has a plain and ordinary meaning that is not coextensive with “active moiety.” It encompasses the active ingredient that exists in the product as administered and as approved—as specified by the FDA and designated on the product’s label—or changes to that active ingredient which serve only to make it a salt or an ester. It does not encompass a metabolite of the active ingredient or its de-esterified form. This case is unlike Glaxo or Pfizer in that it concerns a de-esterified compound, not an ester or salt.

The Federal Circuit also held that Biogen could not use the doctrine of equivalents to establish infringement:

To infringe a patent claim extended under § 156, an accused product or process must meet, either literally or through equivalence, each individual element of the claim. See Johnson & Johnston Assocs. Inc. v. R.E. Serv. Co., 285 F.3d 1046, 1052 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (en banc). But such a product or process cannot logically infringe an extended patent claim under equivalence if it is statutorily not included in the extension under § 156. That would make judge-made law prevail over statute.

What Did Pfizer Say?

Biogen argued that its position was supported by the “active moiety” analysis in Pfizer. In that case, the Federal Circuit found that Pfizer’s extended patent rights based on approval of amlodipine besylate reached the accused product, amlodipine mesylate, both being different salts of the active moiety amlodipine. Indeed, in Pfizer the Federal Circuit stated:

The FDA ruled that “the term ‘active ingredient’ as used in the phrase ‘active ingredient including any salt or ester of the active ingredient’ means active moiety.” Abbreviated New Drug Application Regulations: Patent and Exclusivity Provisions, 59 Fed. Reg. 50,338, 50,358 (F.D.A. Oct. 3, 1994). The FDA has defined “active moiety” as “the molecule or ion, excluding those appended portions of the molecule that cause the drug to be an ester, salt ..․ responsible for the physiological or pharmacological action of the drug substance.” 21 C.F.R. § 314.108(a).

(The FDA rule cited in Pfizer appears in Part 314, which relates to “Applications for FDA Approval to Market A New Drug.” In contrast, the FDA rule cited in Biogen appears in Part 210, which relates to “Current Good Manufacturing Practice in Manufacturing, Processing, Packing, or Holding of Drugs….”)

Judge Lourie had joined the majority decision in Pfizer, but in Biogen distinguished that case, stating:

In Pfizer, we considered whether an extension for amlodipine encompassed a § 505(b)(2) applicant’s amlodipine maleate product under § 156(b)(2). We held that it did because amlodipine maleate is a salt of the active ingredient, amlodipine, and was therefore the same product under § 156(f). Pfizer, 359 F.3d at 1366 (“We conclude that the active ingredient is amlodipine . . . .”). Pfizer does not govern this case because MMF is not a salt of DMF.

As Biogen pointed out in its petition for rehearing en banc, however, the approved product in Pfizer was amlodipine besylate, not amlodipine. It is the Federal Circuit in Pfizer who determined that the “active ingredient” in the approved product was “amlodipine,” based on the FDA guidance quoted above. It may be that MMF is not an ester of DMF, but neither was Dr. Reddy’s amlodipine maleate a salt of Pfizer’s amlodipine besylate. Yet, the court reached an opposite conclusion on infringement.

/>i

/>i