Manufacturers of dietary supplements, food, beverages, and even medical devices can breathe a little easier following the Supreme Court’s denial of certiorari this week in a case seeking to overturn a First Circuit decision holding that state consumer protection claims that rely on violations of the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FDCA”) are impliedly preempted. In DiCroce v. McNeil Industries, 82 F. 4th 35 (1st Cir. 2023), the plaintiff brought a class action against a supplement manufacturer and its parent company, Johnson & Johnson, asserting state law deceptive trade practices and false advertising claims related to Lactaid, a supplement for individuals with lactose intolerance. The plaintiff argued Lactaid’s labeling was misleading because the product treats a disease, is therefore a drug rather than a supplement, and the label misled consumers into believing Food & Drug Administration (“FDA”) approval of the product was not required. According to plaintiff, Lactaid was a drug that was being deceptively marketed as a dietary supplement.

While the claims plaintiff asserted were state law claims, the underlying basis for the allegations was the assertion that Lactaid’s label violated the FDCA’s labeling requirements and was therefore misleading to consumers. The FDCA provides for exclusive enforcement by the FDA and has no private right of action. Where state law claims are based on allegations that the defendant violated a statute that has no private right of action and leaves enforcement to a regulatory body, the claims can be barred by the doctrine of implied preemption, meaning courts defer enforcement of FDCA violations to the FDA. That is exactly what happened in this case.

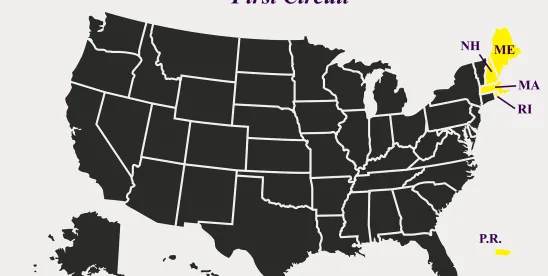

The trial court dismissed the plaintiff’s claims and the First Circuit affirmed, finding that state consumer protection claims that rise and fall on violations of the FDCA are impliedly preempted by the FDA’s exclusive statutory enforcement authority. Relying on prior decisions in the food labeling and medical devices space, the court reiterated the importance of the substance of the claims asserted rather than their form. Because the claims were impliedly preempted, the court found no merit in plaintiff’s argument that the trial court should have allowed the claims to proceed past the pleading stage. After losing at the First Circuit, the plaintiff asked the Supreme Court to weigh in on the issue. The Supreme Court refused, which leaves the ruling by the First Circuit that plaintiff’s claims were impliedly preempted intact.

So, what does this mean for manufacturers of FDA-regulated products? As these businesses (and their counsel) are well aware, plaintiffs frequently present class claims as violations of state consumer protection law that rise and fall on alleged violations of the FDCA. For example, a plaintiff might argue that a beverage label is misleading and therefore violates state consumer protection laws where it fails to comply with the FDA’s characterizing flavor regulation and suggests that a product contains a natural ingredient (such as lemon) when in fact it does not. Despite the argument that the label violates the FDCA, we expect that plaintiffs will now have to argue that the label also independently violates state law (such as a state food and drug act or advertising law) in order to avoid the courts’ deferral of enforcement to the FDA.

The Supreme Court’s denial of certiorari provides an important guidepost for lower courts outside the First Circuit that might be presented with similar claims and arguments. While we expect plaintiffs will continue to bring these sorts of claims, this decision provides valuable ammunition for defendant manufacturers faced with claims of FDCA violations cloaked as violations of state law.

/>i

/>i