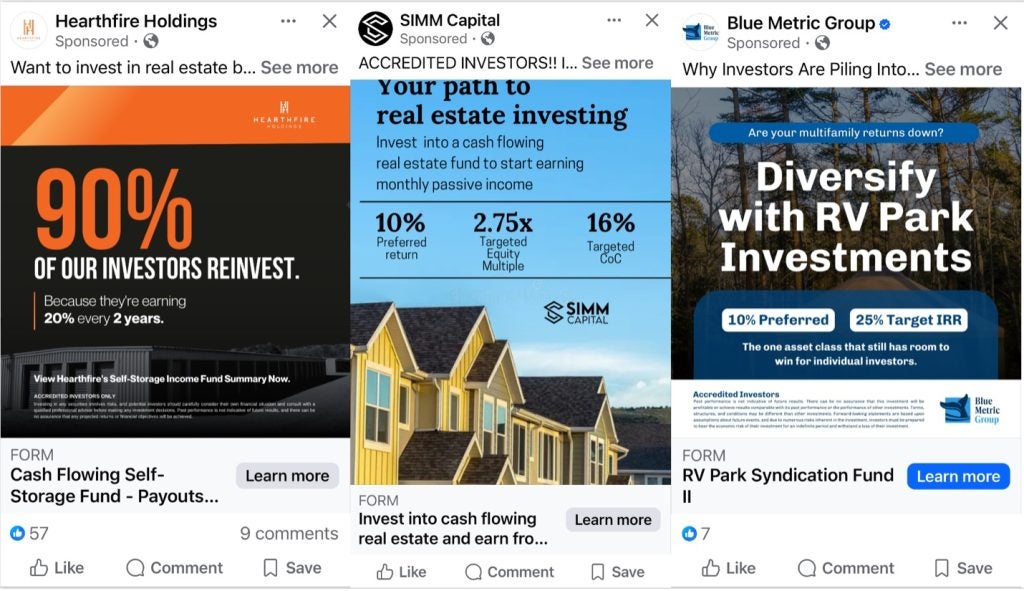

My Facebook feed has, since mid-March [i], become a wasteland of companies peddling their equity, bombarding me with the ‘opportunity’ to invest in them. It’s infuriating. Consider this a PSA to point out that investment advice should come from professionals with the requisite education, experience, and track record necessary to be trusted, who come to you through a warm introduction from someone you trust.

Just as you should ignore cold calls from would-be advisors (excellent advisors get their business from referrals, not cold calls or billboards), so, too, should you ignore Facebook posts promoting any particular investment, particularly one from the company whose post it is (excellent investment opportunities do not need to spend money advertising for investors).

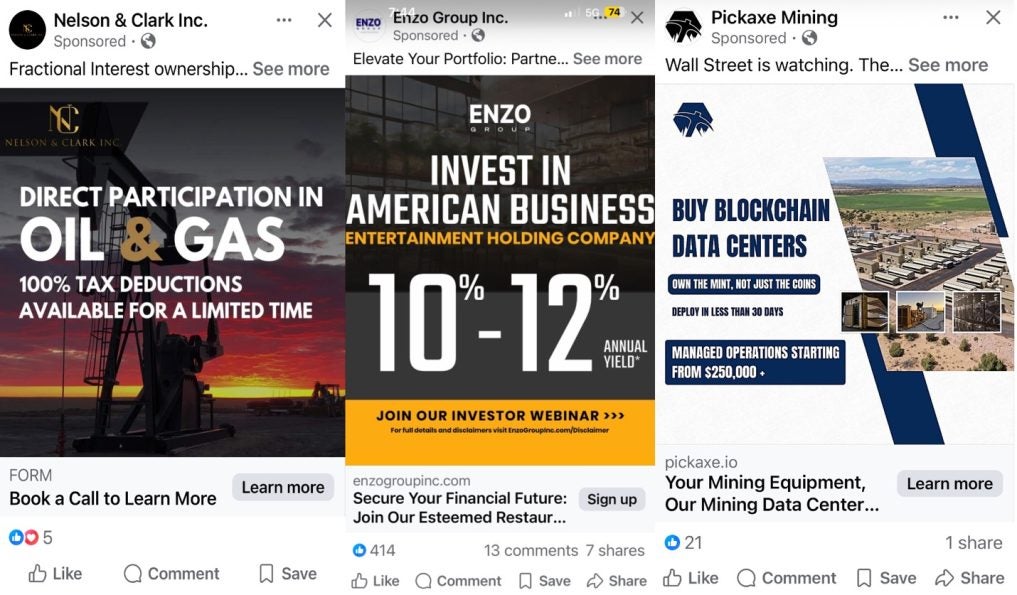

Here are some examples of what I’m referring to:

It’s the Roaring 20s (Again)

In the 1920s, the stock market became the nation’s favorite casino. Shoeshine boys, secretaries, and schoolteachers alike jumped headfirst into equities, often on margin and with little understanding of the risks. [ii] With little regulation and rampant speculation, fortunes were made, and just as quickly lost when the bubble burst in 1929. It was a nationwide game of musical chairs, and when the music stopped, most people were left standing.

After the Crash: We Built a Fortress

In the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, America didn’t just suffer economic devastation; it suffered an existential crisis. It turns out that when your life savings vanish overnight because some cigar-chomping banker in pinstripes thought margin loans were a good idea, faith in the system evaporates. So, Washington stepped in, not timidly, but with a regulatory flamethrower. [iii]

The Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 were cornerstones of this effort, demanding transparency and birthing the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to make Wall Street more like a zoo and less like the jungle it had become. Glass-Steagall severed ties between commercial and investment banking like a stern divorce lawyer. And the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was created so that your local bank going under didn’t mean your money did, too.

These reforms built a regulatory fortress. But like some fortresses, the walls took on battle scars over the years, and, if you’ve been paying attention to the last few decades (or saw The Wolf of Wall Street), they all but collapsed. [iv]

How Soon We Forget: Eroding Walls

Fast forward to 1999. Congress, under the seductive sway of ‘financial innovation’ and an army of lobbyists, passed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, repealing key provisions of Glass-Steagall. And just like that, ‘financial supermarkets’ were back. Nothing stopped you if you wanted to make home loans in the morning and package them into exotic derivatives by lunch. What could go wrong? (Spoiler: 2008.)

Post-crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act tried to hammer things back into shape, but it didn’t take long for its teeth to be dulled by regulatory attrition and partisan arm-wrestling. Then the JOBS Act of 2012, a well-intentioned but complex beast, came along.

Come On In, the Water’s Fine

The JOBS Act promised to democratize capital raising. And in fairness, it did open doors.

Accredited investors (those whose income or wealth exceeds certain minimums or, since 2020, for whom “reliable alternative indicators of financial sophistication” qualify them as such) can now invest in alternative assets with far more ease than before. Everyone else can also access a subset of alternative assets they were previously forbidden from investing in. Are these good things? Like so many things in life, it depends.

Once upon a time, a startup raising capital under Regulation D had to do some homework: income verification, net worth checks, etc. But since March 12th, issuers can rely on an investor’s mere representation that they qualify. It’s like letting people board a rollercoaster by checking a box that says, ‘Yes, I’m tall enough.’ [v]

A Crowdfunding Kiosk by the Moat

The JOBS Act also established a new kind of angel investing under Title III of the Act, which is also known as the ‘crowdfunding exemption.’ This profound shift allowed all Americans, not just the wealthiest, to invest in startups and small businesses over the internet. On May 16, 2016, the SEC adopted Regulation Crowdfunding to implement Title III crowdfunding. Soon thereafter, crowdfunding portals, open to all investors, began launching. [vi]

That’s not necessarily bad. Democratizing capital formation has its virtues. But it also creates new risks (and dusts off old ones). Without strong oversight and a skeptical eye, the gap between innovation and exploitation can narrow faster than a WeWork valuation.

The New ‘Wild West’

The financial guardrails built in the 1930s were meant to keep the system from imploding under the weight of its own greed. Over time, those guardrails weren’t just loosened, they were rebranded as ‘red tape’. And while tech-driven capital markets may no longer resemble the smoke-filled back rooms of the 1920s, the human impulses behind them haven’t evolved much.

Whether today’s patchwork of laws, portals, and good intentions can prevent another collapse is an open question. But history suggests that when the music stops, and it always does, some will be left holding the bag.

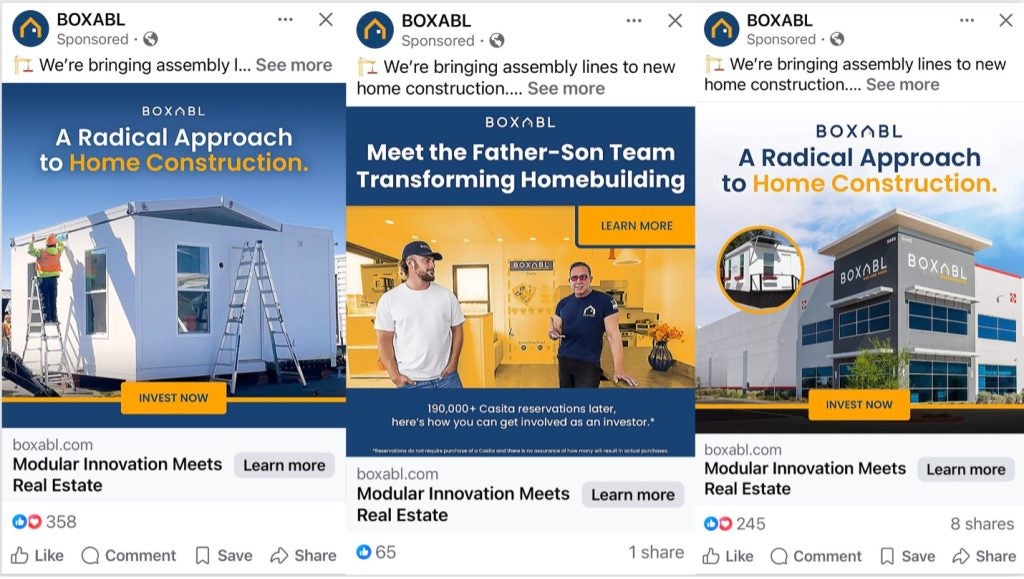

This brings me back to where I started: my Facebook feed has transformed into a digital Times Square circa 1985. It’s a nonstop neon carnival pitching everything from cannabis startups promising ‘high’ returns (see what I did there?) to cutting-edge AI ventures guaranteed to become the next Apple or Amazon. Here are some screenshot examples:

As I wrote back in 2016, the democratization of investing is a double-edged sword. Sure, fewer hoops mean issuers can cast wider nets with considerably less effort and expense. That’s fantastic news for issuers who previously found verifying accredited investors a bureaucratic nightmare. On the flip side, investors now swim in glossy ads that lean hard into flashiness rather than financial fundamentals; more ‘razzle-dazzle,’ less due diligence. [vii]

These companies must be spending serious cash on these ads. I wonder where they’re getting it from? One obvious answer may be that some of the money people invest in these companies has been used to pay for the ads, to help sell more people on investing more money. What does that remind you of?

Here’s a hint: rhymes with Fonzi.

Either way, the takeaway here should be caution. Easier access doesn’t equate to less risk; it just means quicker entry to potentially dubious deals.

As I’ve previously warned, investing in startups and similar ventures isn’t like tossing cash into a well-diversified mutual fund; it’s more akin to placing bets in Vegas (if that doesn’t sound familiar, go back and read reference 7).

Ironically, one recent poster child for this convergence of accessibility and serious risk hails from Sin City. Enter Boxabl, Inc.

The Boxabl Story

It’s not every day a prefab housing startup claims a near-billion-dollar valuation while still figuring out how to mass-produce a folding house. But that’s precisely what Boxabl, Inc. has done. According to its latest Form 10-K filed with the SEC for the year ending December 31, 2024, the company’s trajectory is as attention-grabbing as it is anxiety-inducing.

Here are the most concerning aspects of Boxabl’s SEC filing, and why investors might want to put down the Kool-Aid.

1. Big Valuation, Bigger Losses

In its 10-K, Boxabl reported that the market value of its voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates was approximately $974 million. That would be impressive if it were riding a wave of profits or market traction. Instead, Boxabl continues to burn through cash, with no assurance of profitability anytime soon. [viii]

2. Manufacturing Ambiguity

The company acknowledges that its ability to scale production remains uncertain. [ix] While it’s invested in a production facility and automation, there is a stark difference between building a few houses and manufacturing thousands at consistent quality and speed. Other modular startups have collapsed under similar strain.

3. Supply Chain and Cost Pressures

Boxabl notes that disruptions in its supply chain could materially affect its operations. [x] In its commentary, Boxabl does address the recent tariffs imposed by the Trump administration noting that:

“[O]ur operations are currently supported by a substantial inventory of completed units manufactured prior to the effective dates of the tariff adjustments, which reduces our near-term exposure to increased costs associated with imported materials… [and that]…as we transition into the next phase of our product development, including Phase 2, our sourcing strategy reflects a greater emphasis on domestic procurement.”

However, as with any manufacturer, especially one operating on thin margins, even modest material cost increases or component delivery delays could derail operations. Given the unpredictability of tariffs and the current low-heat trade war that could explode at any minute, manufacturers like Boxabl face a very uncertain future regarding materials sourcing and costs.

4. Regulatory Roadblocks

Boxabl markets its product as a universally deployable housing solution, but the reality is far messier. Local zoning laws, building codes, and permitting regimes vary dramatically by municipality. The 10-K admits these hurdles could affect the company’s ability to expand. [xi]

5. Legal Landmines

Boxabl disclosed that it is involved in legal proceedings that could materially affect its operations or financial condition. [xii] One concern is pending claims from several investors who fell victim to a former Boxabl employee who had issued fraudulent securities in Boxabl’s name. Though Boxabl obtained a default judgment in its favor and denies liability for these claims, it notes that it is not currently possible to calculate its potential exposure.

Germane to the concerns I’ve raised regarding the increase of social media advertising targeting accredited investors, Boxabl also notes that it has “received claims from various parties alleging that it violated certain California laws, including the Trap and Trace Law and California Privacy Laws relating to its Facebook postings.” [xiii]

6. Dilution

As of 12/31/24 Boxabl had authorized a whopping 3 billion shares, and all 3 billion are already outstanding. [xiv] That high float signals a risk of dilution and reflects a capital-raising strategy dependent on retail enthusiasm (dare I say ‘hype’) more than institutional buy-in.

7. Speaking of Moats

Boxabl looks cool, but I question whether it has the intellectual property to provide enough of a moat. [xv] A review of its 10-K does, however, suggest it has many factory, furniture, structural, and transportation patents of varying status and jurisdiction:

- Factory: 3 Granted/Completed, 5 Published, 2 Pending

- Furniture: 1 Published, 3 Pending

- Structural: 19 Granted/Completed/Allowed, 37 Published,12 Pending

- Transportation: 30 Granted/Completed,11 Published

Boxabl also highlights its ownership of the BOXABL trademark, registered in the US, EU, and “in certain other countries around the world,” and notes that it “aggressively enforces its rights in the BOXABL trademark whenever third-party uses of similar names are encountered.” On the other hand, Facebook’s algorithm has fed me some companies that look a lot like Boxabl. Here’s one:

9. The Crowdfunding Game

Boxabl is funding itself primarily through crowdfunding. [xvi] That may suggest that traditional capital sources are cautious, if not skeptical. While crowdfunding can democratize investment, it attracts less sophisticated capital that may not appreciate the risks.

Past Investigations of Boxabl

A 2023 investigation by Business Insider, “Tiny Homes, Big Problems,” outlines many of the same concerns shared here, chief among them that Boxabl’s business model doesn’t necessarily jive with reality.

For instance, Business Insider notes that initially, Boxabl estimated it could produce each casita unit for $30,000. That number now stands at $60,000 according to the 10-K. Ultimately, Business Insider found that each casita could cost even more — $100,000+ when including labor, materials, and overhead. It should be noted that the company is now offering a more accessible ‘Baby Box,’ which has an MSRP of $30,000. However, this price reflects a $10,000 increase from the introductory order price of $19,999 when it was launched not that long ago in January 2025.

More troubling still are the spending habits and Boxabl stock sell-off’s made by the co-founders, Paolo and Galiano Tiramani, which Business Insider highlights in its investigation.

The Business Insider piece quotes Charles Elson, Retired Professor of Finance and Edgar S. Woolard Chair in Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware and Founding Director of the Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance, who observes “Any time you see a chief executive or controlling shareholder pulling money out of a young, growing company, that’s not a good sign…It suggests they have a better place to put their assets than their own firm.”

Kevin Paffrath of HouseHack and the Meet Kevin YouTube channel went further. In his 2023 video, Paffrath walks through many of the same concerns outlined in the Business Insider investigation, but goes so far as to allege Boxabl may be committing fraud. The video is quite detailed and worth the time.

In September 2023, Boxabl became the subject of an SEC investigation, which ultimately concluded in the SEC’s decision to take no enforcement action. In a press release following the SEC’s findings, Boxabl noted that “with the appointment of the Board of Directors, BOXABL Inc. has significantly increased its focus on corporate governance and compliance [and that] the company has also implemented new policies and procedures, including a new Code of Ethics and Business Conduct, and invested in best-in-class systems.”

Boxabl is selling a seductive vision: fast, affordable housing that unfolds like origami. However, pieces by the lay press, such as those highlighted above and the 10-K, reveal that the company is still struggling to execute its vision. Massive dilution, operational uncertainty, and legal risk cloud its potentially glossy future. Investors intrigued by the story would do well to read the fine print and maybe build their dream house somewhere else.

Offer Ends Soon!

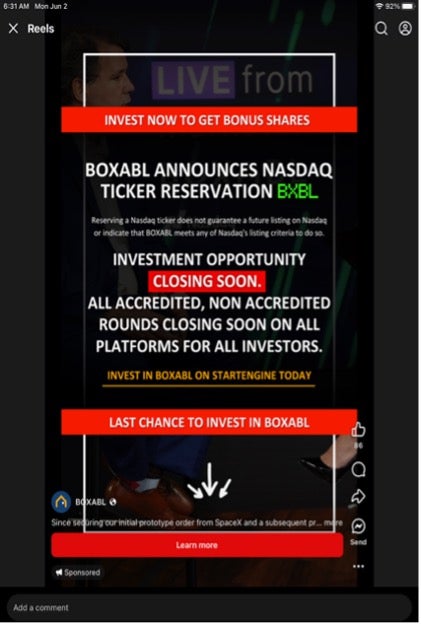

Five things in particular strike me as particularly obnoxious about Boxabl’s ads:

- A while ago, many ads started noting that Boxabl had reserved a ticker symbol. Although the ads note that this does not indicate when or if the company will go public, it has some potential, obvious psychological effects.

- More recently, it announced that the investment opportunity is closing June 24th. Note that it has not foreclosed the possibility of another chance later. Want to bet that happens sooner than later?

- Even more recently, it announced adopting a “Bitcoin Treasury Reserve Strategy.” This reminds me of the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s, when companies saw significant boosts in their stock prices simply by adding ‘.com’ to their names, regardless of whether they had any meaningful internet strategy. Feel a sense of déjà vu?

- Oh, there’s also its most recent announcement of its intent to merge with a SPAC.

Yep, just about two weeks before “all current investment for all types of investors on ALL platforms” will close, Boxabl announced a non-binding letter of intent to merge with a NASDAQ-listed SPAC. What timing!

What’s a SPAC, you ask? The short version is that it’s a publicly traded shell company formed strictly to raise capital through an IPO to acquire or merge with an existing private company. It has no commercial operations when it is first created — no products, no services, and no revenue. It’s often called a ‘blank check company’ because investors put money into it without knowing what company the SPAC will eventually acquire. [xvii]

How have SPACs done as a whole? Michael C. Eisenband of FTI Consulting wrote last Summer that:

“Currently, 85% of some 300 SPACs that completed reverse mergers through 2022 are trading below their IPO price compared to 80% a year ago and 64% in June 2022. Worse yet, the average SPAC is valued currently at just 43% of its IPO price compared to 50% at the end of 2023 and 67% a year ago. This compares very unfavorably to a 15% return for the S&P 500 in 1H24 and a 23% return since June 2023.” [xviii]

- There’s also the opportunity to earn “BONUS shares!”

These seem more like ad strategies Don Draper would gin up to sell cigarettes or Jaguars than a sound basis for an investment. [xix]

I understand ‘buy two shirts, get one free.’ But doing this with shares of a company? No. That should not be a thing.

Taking a step back, Boxabl appears to have disclosed everything it should disclose. It’s a risky ‘investment’ (I don’t consider it an investment at all; it’s a gamble in my view) and doesn’t say otherwise. After all, right on the homepage of its website, it tells you things like:

- It’s raised more than $200 million yet has built only about 600 houses

- While 190,000 people have reserved a casita, a reservation does not require a purchase

- It’s seeking to raise $1 billion, yet, as noted above, has raised only about $200 million- thus all but promising massive dilution

Indeed, promises will likely not be broken because few if any promises are being made. Boxabl speaks of its vision, what it could do, what it thinks it can do, and what it hopes to do. Nor do I doubt that Boxabl’s various filings with the SEC do what they are supposed to do. [xx] I think, Boxabl is likely following the letter of the law in how it’s raising money.

All I’m saying is that:

- Having read its SEC filings, I would not invest.

- I seriously doubt most people who have invested have read the SEC filings.

- I think Boxabl’s ads are excellent — good enough to persuade people to invest without reading the SEC filings or seeking advice from a trusted professional.

- The law should be changed.

A More General Word of Caution

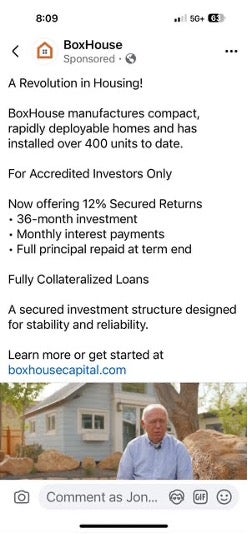

This article, and my point, are not really about Boxabl. I just happened to pick it as an example. Indeed, I’ve seen many companies raising money on Facebook. Here are some more screenshots I grabbed recently:

My ultimate point is this: there were good reasons Congress decided to limit who could invest in certain riskier asset classes so many years ago. And there were good reasons that those promoting those investment opportunities could not do so using radio, television, or billboard ads.

I’m not saying the extent of the prohibitions was all good or that relaxing them was all bad. I’m just saying that people would be better off limiting their social media-driven purchases to consumer goods and working with qualified and trusted advisors when making investment decisions.

References

[i] There’s a reason for the mid-March timing. Keep reading.

[ii] The reference to shoeshine boys is not intended to be sexist. Historical accounts and contemporary fiction are replete with references to shoeshine boys but devoid of references to shoeshine girls. Certainly, Mr. Alger’s writing focused on only the former and never the latter.

[iii] To be fair, that flamethrower possibly prevented a revolution and certainly helped feed people much faster than otherwise would have happened. Of course, I’m thinking more of things like the WPA, CCC, CWA, and the NYA. As an aside, if you’re looking for a great podcast about US history, check out Professor Greg Jackson’s History That Doesn’t Suck.

[iv] Did you know FDR’s phrase ‘New Deal’ was a play on the older ‘square deal,’ famously used by his fifth cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, decades earlier? And although their relationship was quite distant from a genealogical perspective, Eleanor was Teddy’s niece (again, courtesy of Professor Jackson and HTDS).

[v] For the full story, read “Alternative Assets and the “Average” Accredited Investor Installment #3.” If you want to take a deeper dive on what it means to be an accredited investor, read “Alternative Assets and the “Average” Accredited Investor Installment #1.” For more on Reg. D and Rules 506(c) and (d), read “Alternative Assets and the “Average” Accredited Investor Installment #6.”

[vi] For more on Title III crowdfunding, read “Alternative Assets and the “Average” Accredited Investor Installment #7.”

[vii] Counterarguments made in support of the JOBS Act (and against the legal regime at the time that made it so that only accredited investors could legally access the potential upside of early-stage investing), included that it was paternalistic and inconsistent for the government to allow any adult to walk into a casino yet not allow the same people to access the potential upside of early-stage investing.

Those on record in this regard included Steve Case (co-founder of AOL) and Marc Andreessen (co-founder of Netscape). Case, by the way, in 2010, negotiated the largest merger in history (to that point), joining AOL and Time Warner. The dot-com bubble burst, and the combined company’s valuation crashed just a couple of months later.

For clarity, this cemented Case as one of the greatest dealmakers of all time (at least in my opinion) because despite having less revenue and profit than Time Warner, Case used AOL’s overvalued stock as currency to engineer its ownership of 45% of a combined company whose assets (thanks to what Time Warner brought to the table) included CNN, HBO, Time Magazine, Warner Bros., and Time Warner Cable. I remember this well because I owned shares of Turner Broadcasting System that converted Time Warner stock when the former merged into the latter (and sold it, long before the AOL-Time Warner merger).

[viii] Form 10-K [2024] Part II, Item 8

[ix] Form 10-K [2024] Part II, Item 5.

[x] Form 10-K [2024] Part I, Item 1A – Risk Factors

[xi] Form 10-K [2024] Part I, Item 1 – Business.

[xii] Form 10-K [2024] Part I, Item 3 – Legal Proceedings

[xiii] See Form 10-K [2024] Part I, Item 3-Other Litigation. For more information about trap and trace cases see Recent California Invasion of Privacy Act Cases on Pen Registers and Trap-and-Trace Devices (last visited 5/28/25).

[xiv] Form 10-K [2024] Cover Page.

[xv] In this context, ‘moat’ refers to a sustainable competitive advantage. See VanEck: What Makes a Moat? Morningstar’s Five Sources of Moat. (last visited 6/6/25).

[xvi] Form 10-K [2024] Part II, Item 5 and Offering Summary.

[xvii] A thorough and thoroughly well written summary about SPACs is The Great SPAC Scam: Why SPACs Are a Great Deal for Celebrity Sponsors, But Not Companies or Normal Investors written by Brian DeChesare. With header section titles such as “The SPAC Scam Explained” and “Why SPACs Are a Racket,” it’s a fun read.

[xviii] Not Even a Raging Bull Market Can Rescue SPACs, published at https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2024/07/29/not-even-a-raging-bull-market-can-rescue-spacs/.

[xix] True, he preferred whiskey, but one does not ‘whiskey up’ ideas.

[xx] There is, in particular, no doubt in my view that Boxabl’s Offering Circular Dated June 25, 2024, does a bang-up job of doing what it is supposed to do. The risk factors certainly appear thorough. You can access all of Boxabl’s SEC filings here.

©2025. DailyDACTM, LLC d/b/a/ Financial PoiseTM. This article is subject to the disclaimers found here.

/>i

/>i