The Dutch Supreme Court issued two rulings that provide guidance on how to apply the Dutch dividend withholding tax exemption, more specifically the anti-abuse provisions therein. Under certain conditions, the Netherlands fully exempts dividends Dutch companies distribute from dividend withholding tax, but the exemption may be denied in cases of abuse. The Dutch Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision and ruled in both cases that the structures were abusive at the time the Dutch subsidiary distributed the dividends. This update is relevant for multinational groups that have a Dutch subsidiary as part of their group structure. This GT Alert outlines considerations for multinational companies with Dutch subsidiaries.

Supreme Court Analysis: When Anti-Abuse Provisions Override Tax Exemptions

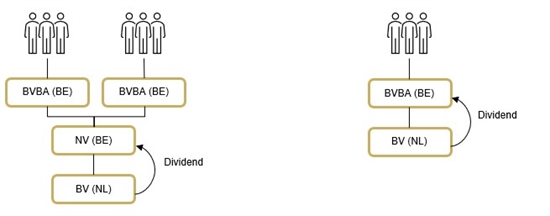

In both cases, the foreign shareholder is a Belgian company, each (ultimately) owned by Belgian family members. These Belgian companies own shares in – amongst others – Dutch subsidiaries, which in turn own multiple shareholdings. The Belgian companies invoked the Dutch dividend withholding tax exemption on dividends distributed by the Dutch subsidiaries. The Dutch tax authorities denied the application of the exemption with reference to the anti-abuse measures. Below we included two simplified structures of both cases.

The Dutch Court of Appeal (lower court) ruled in the Dutch tax authorities’ favor, finding that the anti-abuse rules apply and that the exemption is not applicable. For a structure to be considered abusive, a structure must have the main purpose or one of the main purposes to avoid dividend withholding tax, and the structure or transaction must be artificial. For this purpose, all facts and circumstances must be considered. Having some form of substance or conducting a material business enterprise at shareholder level may not always be sufficient to rebut abuse.

The lower court concluded that although one of the Belgian shareholders was engaged in an active business enterprise, the structure was still considered artificial because the shareholder did not actively engage with its Dutch subsidiary. As a result, the shares in the Dutch subsidiary could not be “functionally allocated” to the shareholder’s active business enterprise.

The court additionally ruled that the lack of substance and other real economic activity at the shareholder level contributed to the conclusion of artificiality. Another indicator of an abusive structure follows from the fact that the Belgian shareholder could not freely dispose of the dividends received as this authority factually lied with its (ultimate) shareholders.

The Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision and ruled that the Dutch law is applied correctly in conjunction with EU legislation. A structure may be considered artificial if it can no longer be justified by the economic and commercial advantages associated with it. The fact that in one of the cases the shareholder had existed since 1991 did not prevent the structure from becoming abusive after the set-up.

Compliance Considerations for Dutch Subsidiary Structures

Multinational companies that have a Dutch subsidiary as part of their group structure may wish to evaluate the following strategies to mitigate the risk that a foreign shareholder in the group structure cannot apply the Dutch dividend withholding tax exemption on dividends received from its Dutch subsidiary.

- Document commercial rationale: Companies should maintain records to rebut Dutch tax authorities’ claims of abuse. It may be beneficial to determine and record the reasons for the intermediate shareholder (i.e., the foreign company owning shares in the Dutch subsidiary). In the recent court cases, the court ruled that “obvious” reasons for having a holding company are not sufficient. For example, the fact that a holding company limits the liability with respect to the Dutch subsidiary’s debt was found insufficient to counter abuse. The courts also determined that the circumstance that ultimate shareholders can more easily sell their shares in the holding company than their investment in the Dutch subsidiary as a separate asset was not sufficient. Further, although often the case in practice, courts have found that the fact that ultimate individual shareholders incorporate a holding company in their resident jurisdiction may not be sufficient to counter abuse.

- Structure monitoring: If significant changes in group structure occur, companies should review whether these erode the commercial and economic advantages of the structure. The abuse test is a continuous test. For example, if a company was engaged in an active business enterprise but sells its assets and functions except for the Dutch subsidiary, it should reassess whether it is commercially and economically reasonable that the company still owns the shares in the Dutch subsidiary. Instead, after the transfer of assets and functions it may commercially and economically make more sense to have the ultimate shareholders own the shares in the Dutch subsidiary directly.

- Operational substance considerations: Ensure holding companies have meaningful operational substance. If the holding company has no relevant substance in the form of an office space or employees, there should be other circumstances that show real economic activity. In one of the recent cases, the holding company’s only assets in addition to the Dutch subsidiary were two classic cars, which were held as a passive investment. The court found this did not demonstrate sufficient economic activity. However, based on these rulings, substance alone may not be sufficient to invoke the exemption.

- Functional attribution analysis: Based on these court decisions, a shareholder may need to substantiate that the shares in the Dutch subsidiary are attributable to its active business enterprise. If the shareholder is a holding company, this might be established by having the shareholder actively manage and engage with its subsidiary.

- Decision-making authority structure: A holding company should have decision-making authority over the dividends it receives from its Dutch subsidiary. In the recent cases, the Belgian families had full discretion over the distribution or reinvestment of dividends the holding company received from its Dutch subsidiary. As a result, the court found that the holding company could not freely dispose of the dividends. A key factor in this case was that the holding company did not have the authority in relation to the decision to either distribute or reinvest the dividends received from the Dutch subsidiary because the board of the company only consisted of direct or indirect shareholders. These rulings suggest that a holding company may need to be able to freely dispose of the dividends received and be able to substantiate its authority.

These considerations may also be relevant to the foreign substantial shareholding regime, a Dutch anti-abuse rule that, if applicable, includes dividends and capital gains in Dutch corporate income taxation.

/>i

/>i