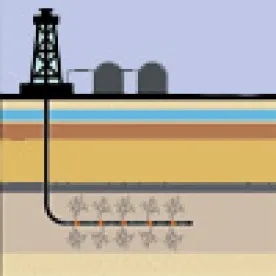

Earlier this month, US EPA released its long-awaited draft assessment on the impact of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) on the nation’s drinking water resources. The assessment, titled Assessment of the Potential Impacts of Hydraulic Fracturing for Oil and Gas on Drinking Water Resources, represents over four years of study into the potential of hydraulic fracturing to impact current and future drinking water sources in the US. While finding several “potential mechanisms by which hydraulic fracturing could affect drinking water resources,” the assessment ultimately does “not find evidence that these mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources in the United States.”

The conclusions of US EPA’s years-long fracking study significantly undermine challenges to the oil and gas industry’s use of the fracking process for hydrocarbon extraction on the grounds that it poses a threat to underground water supplies. Nonetheless, US EPA’s report leaves open the door to future challenges, noting several “potential vulnerabilities in the water lifecycle” and raising questions about whether the lack of evidence of drinking water impacts found represents “a rarity of effects on drinking water resources” or “other limiting factors” such as insufficient data, “the paucity of long-term systematic studies,” or the presence of other sources of contamination precluding a definitive link between fracking and an impact.

US EPA’s assessment identifies and describes a range of potential impacts on drinking water during each phase of its water cycle, water acquisition, chemical mixing, well injection, flowback and produced water, and wastewater treatment and waste disposal. Where available, the assessment identifies recent examples where hydraulic fracturing has resulted in impacts to water quality and, where no examples are available, identifies areas for further research. In each case, however, US EPA ultimately concludes that there is insufficient evidence to indicate a systemic threat to the nation’s drinking water from hydraulic fracturing.

With respect to water acquisition, for example, the assessment notes that surface water withdrawals for hydraulic fracturing “may lower water levels and alter stream flow, potentially decreasing a stream’s capacity to dilute contaminants.” The assessment identifies areas in both Louisiana and Southern Texas where fracking water consumption was investigated for its contribution to low water levels, and finds there remains a chance that “[w]ater acquisition for hydraulic fracturing has the potential to impact drinking water resources by affecting drinking water quantity and quality.” The Assessment acknowledges, however, that US EPA also “did not find a case where hydraulic fracturing water use by itself caused a drinking water well or stream to run dry” and that “[m]anagement of the rate and timing of surface water withdrawals has been shown to help mitigate potential impacts of hydraulic fracturing withdrawals on water quality.”

Similarly, in examining the potential impacts from well injection itself, one of the most controversial aspects of hydraulic fracturing, US EPA’s assessment notes that, while “problems with the well’s components or improperly sited, designed, or executed hydraulic fracturing operations (or combinations of these) could lead to adverse effects on drinking water resources,” “[a]ppropriately sited, designed, constructed, and operated wells and hydraulic fracturing treatments can reduce the potential for impacts to drinking water resources.”

This approach stands in stark contrast to that taken by the State of New York, which, after conducting its own years-long study into the potential environmental and health impacts of hydraulic fracturing, identified many of the same risks as those found in the draft assessment but finding it could not yet decide whether these risks could be adequately mitigated. As a result of these findings, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation announced this week that hydraulic fracturing will not be permitted in New York State at the present time.

The immediate responses to US EPA’s draft assessment have been mixed, with many focusing on the assessment’s key conclusions that fracking is fundamentally safe and can be done in a manner that does not pose a systematic risk to drinking water. On the other hand, critics of hydraulic fracturing have turned immediately to the cautions in the body of US EPA’s assessment and the examples highlighted in the draft of what can happened when things go wrong, echoing many of the statements made in the NYDEC’s recent findings.

As a draft assessment, much can change before the final assessment is published. In the next several months, US EPA’s Science Advisory Board (SAB) will conduct a review of the draft report, including a public meeting and several teleconferences in September and October of this year. Critics of hydraulic fracturing can be expected to continue to press for further caution in the final assessment and a greater emphasis on the need for more study of the drinking water impacts of hydraulic fracturing. On the other hand, proponents of hydraulic fracturing may see the mixed messages coming from the assessment’s many caveats as problematic, and push to have the final assessment more fully discuss and place on firm footing the long-term safety record of hydraulic fracturing and put into perspective the risks identified in the draft assessment. In preparation for SAB’s review, written statements on the draft report must be submitted to the agency by August 28, 2015.

/>i

/>i