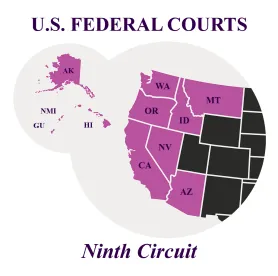

In re Williams-Sonoma, Inc., 947 F.3d 535 (9th Cir. 2020)

Ninth Circuit rules that Rule 26 does not authorize discovery before class certification to help locate a new class representative.

This appeal involved a dispute over a discovery order requiring defendant to provide a list of California purchasers so plaintiff could identify a new class representative. The original plaintiff was a Kentucky resident who sued over alleged violations of California consumer protection laws. After the district court ruled that the Kentucky plaintiff could not bring claims under California law, plaintiff propounded discovery to find a California plaintiff. The district court directed defendant to produce a list of California customers who had purchased bedding products during the relevant period. That order was not appealable, so defendants petitioned for a writ of mandamus.

On a 2-1 vote, the Ninth Circuit granted the writ petition and held the discovery order represented a clear error of law. The Ninth Circuit relied on Oppenheimer Fund, Inc. v. Sanders, 437 U.S. 340 (1978), in which the Supreme Court held the names and addresses of class members were outside the scope of relevant discovery under Rule 26(b)(1). Since plaintiff’s claims and defenses involved the application of Kentucky law, discovery regarding unknown class members for the possible pursuit of California claims was not relevant. Accordingly, the Ninth Circuit held that Rule 26 does not authorize discovery before class certification when the express purpose is to find a new lead plaintiff.

Carpenter v. Petsmart, 2020 WL 996947 (S.D. Cal. Mar. 2, 2020)

Court holds that Bristol-Myers applies to class actions, striking nationwide class allegations.

Plaintiff purchased a “Tiny Tales Homes” habitat from defendant for his pet hamsters, but alleged that, because of a design defect, his pets were able to chew through connector pieces in the habitats and escape, never to be seen again. Plaintiff brought claims on behalf of a nationwide class, alleging claims for breach of the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, breach of warranty, fraud by omission, and unjust enrichment. Defendant moved to strike the nationwide class allegations, arguing among other things the court lacked personal jurisdiction over defendant with respect to claims alleged on behalf of putative class members who purchased Tiny Tales Homes outside of California, and plaintiff lacked standing to assert claims under other states’ laws.

In addressing these issues, the court considered the applicability of Bristol-Myers, where plaintiffs (including non-California residents) brought a mass action in California state court, claiming defendant’s drug product harmed their health. The United States Supreme Court held that “there must be an affiliation between the forum and the underlying controversy, principally, [an] activity or an occurrence that takes place in the forum State and is therefore subject to the State’s regulation.”

The court in Petsmart provided a detailed summary of the three approaches most courts have taken to personal jurisdiction challenges in class actions: (i) Bristol-Myers does not apply to class actions; (ii) Bristol-Myers does apply to class actions; and (iii) the issue should be addressed at class certification. The court ultimately followed the second approach, holding that “the rationale for the holding in Bristol-Myers indicates that if and when the Supreme Court is presented with the question, it will also hold that a court cannot exercise specific personal jurisdiction over a defendant for the claims of unnamed class members that would not be subject to specific personal jurisdiction if asserted as individual claims.” The court also specifically rejected the “class actions are different” argument often used to support the first approach: “[t]he Court, however, is not persuaded that the procedural requirements for a class action constitute a basis for finding that the rationale behind the holding in Bristol-Myers Squibb does not apply to nationwide class actions involving individual claims for which there would not be specific personal jurisdiction if those claims were filed individually.” Thus, the court granted defendant’s motion to strike the nationwide class allegations.

Amaraut v. Sprint/United Management Company, 2020 WL 1820120 (S.D. Cal. Apr. 10, 2020)

Court declines to prevent plaintiffs’ counsel from commenting on, or communicating with, class members in a competing, settled case.

This case involved a hybrid collective and class action—an “opt-in” collective action under the Fair Labor Standards Act and an “opt-out” state-specific class action under state wage and hour law. Defendant settled two related cases (the “Navarette actions”), handled by different plaintiffs’ counsel. Plaintiffs moved to compel production of the contact information for class members in the settled cases, and the court granted the motion. Defendant moved to limit communications by plaintiffs and their counsel, to prevent them from: (1) commenting on the settlement of the Navarette actions; (2) providing an opinion regarding class members’ rights in the settlement; and (3) encouraging class members to opt out.

The court denied defendant’s motion. Noting its “duty and broad authority to exercise control over a class action and to enter appropriate orders governing the conduct of counsel and parties,” the court explained that any such order is “subject to restrictions mandated by the First Amendment and the Federal Rules.” The court emphasized an order restricting communications must be based on a “clear record and specific findings” of the potential for serious abuse arising from the communications. Although the court acknowledged that plaintiffs’ “words [were] often strong”—for example, referencing a reverse auction and criticizing plaintiffs’ counsel in the Navarette actions—it did not find sufficient evidence of abuse.

Grande v. Eisenhower Med. Ctr., 44 Cal. App. 5th 1147 (2020)

In a joint-employer arrangement, a class of workers can bring a lawsuit against a staffing company, settle that lawsuit, and then bring identical claims against the company where they had been placed to work.

In a 2-1 decision, the California Court of Appeal held an employee’s settlement agreement with a staffing agency on a wage-and-hour claim does not necessarily preclude the employee from later suing the staffing agency’s client, for whom the employee performed services, on the exact same claims.

Plaintiff Lynn Grande was assigned through a temporary staffing agency, FlexCare, LLC (FlexCare), to work as a nurse at Eisenhower Medical Center (EMC). Grande became a named plaintiff in a class action lawsuit against FlexCare brought on behalf of FlexCare employees assigned to hospitals throughout California who alleged standard wage and hour claims, including unpaid overtime and meal and rest break claims. FlexCare settled with the class, and a release of claims was executed. The release included standard language releasing the named defendant’s affiliates. But it did not expressly release EMC or FlexCare’s clients. A year after FlexCare settled with the class, Grande brought a second class action on behalf of all nurses of any staffing agency employed and assigned to work at EMC and alleged the same violations against EMC, which was not a party to the original class action.

FlexCare intervened and argued: (1) the judgment in the FlexCare class action precluded Grande’s claims against EMC on res judicata grounds, and (2) EMC was a released party under the FlexCare settlement agreement. The trial court ruled against FlexCare and EMC on both grounds, and FlexCare appealed.

The California Court of Appeal affirmed, holding EMC was not a released party because the release did not include words such as “clients, joint employers, joint obligors” of FlexCare or reference to “any client of FlexCare as to whom any class member may have provided services through FlexCare.” The court further held that the doctrine of res judicata did not bar Grande’s claims because joint employers generally are not liable for each other’s Labor Code violations under Serrano v. Aerotek, Inc., 21 Cal. App. 5th 773 (2018).

That FlexCare and MC were alleged to be jointly and severally liable and joint employers was not enough to satisfy the privity requirements of res judicata. The court departed from the Second District’s decision in Castillo v. Glenair, Inc., 23 Cal. App. 5th 262 (2018), which held a staffing agency and its client were in privity with each other for purposes of the wage and hour claims and therefore a class of workers cannot bring a lawsuit against a staffing company, settle that lawsuit, and then bring identical claims against the company where they had been placed to work.

Montoya v. Ford Motor Company, 46 Cal. App. 4th 493 (2020)

California court holds that, under China Agritech, Inc. v. Resh, multiple tolling periods in successive putative class actions could not be “stacked” to extend the statute of limitations.

This case involved breach of warranty claims that were time barred absent tolling under the American-Pipe doctrine. Plaintiff purchased a Ford Excursion in April 2003 but did not sue until June 2013. To avoid the statute of limitations, Plaintiff relied on tolling under American Pipe based on two putative class actions. On appeal, defendant argued that plaintiff could not toll the statute of limitations for successive class actions, and the court agreed.

Noting that the issue was one of first impression, the court explained that “[t]he question of whether the equitable tolling made possible in American Pipe should extend to a second class action is a question our federal compatriots have addressed at some length, and we find ourselves in agreement with their resolution of the issue.” The court thus held that tolling for successive class action was improper: “we determine that to toll the statute of limitations during the period of a second class action contravenes the judicial economy and efficiency American Pipe was trying to achieve. To do so would take the law of class actions back full-circle to the pre-1966 class action procedure when putative class members (like [plaintiff]) could wait and see what sort of outcome would be forthcoming in a class action and then decide to opt out and file their own individual suit. Second class action tolling multiplies litigation, rather than consolidating and reducing it. We therefore hold the second class action against Ford did not toll the four-year statute,” and the court reversed the judgment in favor of plaintiff.

/>i

/>i