In a recent post, we discussed the importance of complying with the US Patent and Trademark Office’s duty of disclosure under Rule 56 of the Rules of Practice. This post focuses on the existence of this duty throughout the entire prosecution of a patent application, in a specialized factual context involving a priority application outside the US.

Consider the following fact pattern:

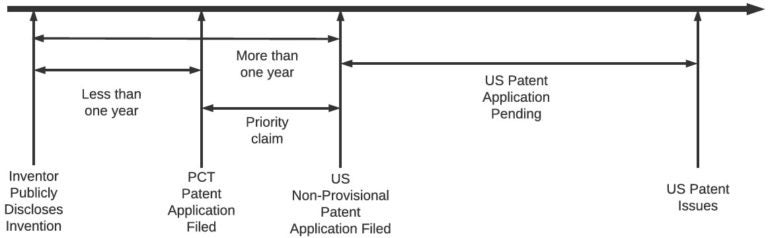

Within one year of an inventor’s public disclosure of an invention outside the US, a PCT application is filed.

More than one year after the public disclosure, a US non-provisional application is filed, claiming priority from the PCT application.

Question: Does the duty of disclosure require telling the USPTO about the prior public disclosure?

Answer: Not necessarily, but it might, and in any event, it is the best practice.

Under the America Invents Act (AIA), 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) provides an exception to the novelty requirement, such that the inventor’s own public disclosure is not prior art if the disclosure occurs one year or less before the effective filing date of the US application. If the US application falls under that exception, it may be possible to avoid citing the inventor’s prior public disclosure during US prosecution. However, the answer is not easy or straightforward.

If the claimed invention in the US non-provisional application is entitled to the filing date of the PCT application, the effective filing date of the claimed invention in the US application would be the filing date of the PCT application. In that circumstance, the exception under 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) would apply, and the prior public disclosure would not qualify as prior art. As a result, technically it would not be necessary to cite the prior public disclosure to the USPTO as part of the duty of disclosure under Rule 56. However, there are a number of issues to consider.

Preliminarily, under US practice, it is possible to “bypass” the normal PCT national stage entry by filing either a “bypass” application, which may contain the same disclosure as the PCT application, or may contain different disclosure from the PCT application. This “bypass” practice is unique to US patent practice (that is, it is not available in other jurisdictions around the world). For purposes of the following discussion, it is necessary only to consider whether the US application contains the same disclosure as the PCT application.

Situation #1:

If the disclosure in the US application is the same as the disclosure in the PCT application, then any claims in the US application may be supported under 35 USC 112, and therefore would be entitled to the filing date of the PCT application.

a) If the PCT application supports the claims in the US application under 35 USC 112, the claimed invention in the US application would have, as an effective filing date, the filing date of the PCT application. In that circumstance, it would be possible to avoid having to cite the prior public disclosure to the USPTO, because the effective filing date of the claimed invention in the US application would be the filing date of the PCT application. Therefore, the novelty exception under 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) would apply, and technically the prior public disclosure would not have to be disclosed to the USPTO.

b) However, even if the disclosure in the US application is the same as the disclosure in the PCT application, it still is possible that the claimed invention in the US application would not be supported under 35 USC 112 for purposes of the PCT application. For example, the US application may be filed with different claims from the claims in the PCT application. Alternatively, during prosecution the US claims could be amended to be different from the claims in the PCT application. Under US law, 35 USC 112 support for the claims in the US application would depend on whether the PCT application shows that the inventor had possession of the claimed invention as of the earlier filing date.

If US-filed claims do not have 35 USC 112 support in the PCT application, then it would be necessary to cite the prior public disclosure to the USPTO during prosecution of the US application, because the effective filing date of the claimed invention in the US application would not be the filing date of the PCT application. As a result, the novelty exception under 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) would not apply, and the prior public disclosure would have to be disclosed to the USPTO.

Situation #2:

If the disclosure in the US application to be filed is not the same as the disclosure of the PCT application, it still is necessary to look at the claimed invention in the US application.

a) If the filed US claims are the same as the PCT claims, the effective filing date of the US claims would be the PCT filing date, and the novelty exception under 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) would apply.

During prosecution, if the US claims are amended, even if arguably consistent with the disclosure in the PCT application, there still may not be 35 USC 112 support for the amended claims. In that event, the novelty exception under 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) would not apply, and the prior public disclosure would have to be disclosed to the USPTO.

b) If the filed US claims are not the same as the PCT claims, there are two other possibilities for the claimed invention in the US application.

i) Similarly to the situation in 1)b) above, even if the claimed invention in the US application technically might rely only on the disclosure of the PCT application, it is possible that PCT application would not support the claimed invention in the US application under 35 USC 112. If that is the case, it would be necessary to cite the prior public disclosure to the USPTO, because the effective filing date of the claimed invention in the US application would not be the filing date of the PCT application. Therefore, the novelty exception under 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) would not apply, and the prior public disclosure would have to be disclosed as part of the USPTO duty of disclosure.

ii) If the claimed invention in the US application relies for support on disclosure in the US application that is not in the PCT application, then the claimed invention in the US application would not be entitled to the filing date of the PCT application. The PCT application would not support the claimed invention in the US application under 35 USC 112. If that is the case, then it would be necessary to cite the prior public disclosure to the USPTO, because the effective filing date of the claimed invention in the US application would not be the filing date of the PCT application. Therefore, the novelty exception under 35 USC 102(b)(1)(A) would not apply, and the prior public disclosure would have to be disclosed as part of the USPTO duty of disclosure.

As should be apparent from the foregoing discussion, the answer is complicated, tends to be fact-specific, and even can change as a function of events during prosecution of the US application.

Takeaway

As a general principle, it is better to disclose more to the USPTO during prosecution as part of the duty of disclosure, rather than less. Such disclosure does not automatically constitute an admission that the disclosure is prior art. In a fact pattern like the one discussed here, staying alert to variations from an earlier priority application can be challenging. It can be difficult to tell whether claims during US prosecution could lose their entitlement to an earlier effective filing date, making a prior disclosure prior art. Telling the USPTO about the prior public disclosure during prosecution can head off possible litigation arguments about the violation of the duty of disclosure.

/>i

/>i