The US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit recently declined to exercise personal jurisdiction over a Japanese shipping company in a $287 million personal injury lawsuit stemming from a collision between a Japanese vessel chartered by the shipping company and a US Navy destroyer. The collision occurred in the territorial waters of Japan and resulted in the deaths of seven American sailors and injuries to several others. Constrained by precedent, the Fifth Circuit looked to due process considerations under the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution — considerations that were developed to assess the extent of a defendant’s state-level contacts — and concluded that personal jurisdiction over the Japanese entity did not exist because it was not essentially “at home” in the United States. However, the panel suggested the case is ripe for en banc review by the full Fifth Circuit to clarify the standards that govern the personal jurisdiction analysis in cases arising under federal law and the related due process considerations under the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution — considerations that focus on a defendant’s nationwide contacts.

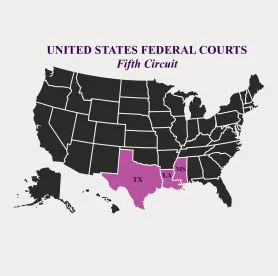

In Douglass v. Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (Nos. 20-30382, 20-30379), family members of the deceased sailors and several of those injured filed two lawsuits in the US District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana seeking damages from the Japanese shipping company, Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (NYK Line), for its negligence in causing the collision. The lawsuits were filed under the federal Death on the High Seas Act, 46 U.S.C. §§ 30301–30308, and the plaintiffs asserted that NYK Line was subject to the court’s general personal jurisdiction under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(k)(2) on the grounds that NYK Line, despite being a foreign corporation, has substantial, systematic, and continuous contacts with the United States. NYK Line quickly moved to have the lawsuits dismissed, arguing that it is not subject to personal jurisdiction in the United States. The Eastern District of Louisiana agreed with NYK Line and dismissed the lawsuits.

An appeal to the Fifth Circuit resulted in the district court’s decision being affirmed in a per curiam decision. The Fifth Circuit’s decision, however, was based not on the merits of the district court’s decision but on the so-called rule of orderliness — a rule that prevents one panel of the Fifth Circuit from overturning a decision issued by a prior panel absent an intervening change in the controlling law. That prior decision, Patterson v. Aker Solutions, Inc., 826 F.3d 231 (5th Cir. 2016), presented similar facts to those before the Fifth Circuit in Douglass, and the panel in Patterson concluded that personal jurisdiction over the foreign defendant did not exist in the United States. The Fifth Circuit declined to exercise personal jurisdiction over the foreign defendant in Patterson because the defendant was not incorporated and did not have its principal place of business in the United States, and its contacts with the United States were not “so substantial and of such a nature” as to render the foreign defendant essentially “at home” in the United States. Constrained by the Patterson decision pursuant to the rule of orderliness, the Fifth Circuit panel in Douglass likewise held that Japanese-headquartered NYK Line is not subject to personal jurisdiction in the United States.

The panel in Douglass, however, specifically recognized the persuasiveness of the arguments in favor of personal jurisdiction. The panel noted that the Patterson decision — which it was bound to follow — was based on the Supreme Court’s decision in Daimler AG v. Bauman, 571 U.S. 117 (2014), and the due process clause of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution. But as the Fifth Circuit recognized in Douglass, the 14th Amendment’s due process clause is rooted in federalism concerns and aims to ensure a defendant’s state-level contacts are sufficient to justify the exercise of personal jurisdiction in a particular state. The due process clause of the Fifth Amendment looks to a defendant’s nationwide contacts in cases arising under federal law that are beyond the jurisdiction of a particular state. According to the Fifth Circuit in Douglass, the Patterson decision improperly constrained the personal jurisdiction analysis by analyzing whether the foreign defendant’s contacts with the United States were “so substantial and of such a nature” as to essentially render the foreign defendant “at home” in the United States — a test developed in 14th Amendment cases such as Daimler. Indeed, the panel in Douglass — together with Judges Elrod and Willett, who authored a concurring opinion — suggested that the same federalism and state sovereignty concerns that underlie the Daimler decision are not present in cases involving the Fifth Amendment and an analysis of a defendant’s nationwide contacts. They reasoned that a defendant with substantial, systematic contacts with the United States as a whole could conceivably be subject to personal jurisdiction in US federal court in a state with which it has such contacts, but not in the courts of a particular state if it is not essentially “at home” in that state.

Despite applying the rule of orderliness and declining to exercise personal jurisdiction over NYK Line, the panel and concurring judges in Douglass suggested that an en banc review by the full Fifth Circuit might be in order to clarify the personal jurisdiction standards in cases arising under federal law and the due process concerns of the Fifth Amendment. The Douglass decision is significant in the maritime space because, as the panel in Douglass recognized, federal law includes maritime law for purposes of personal jurisdiction under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 4(k)(2) and the Fifth Amendment’s due process standards. For the time being, under the Fifth Circuit’s ruling in Douglass, the threshold for obtaining personal jurisdiction over foreign defendants under a general jurisdiction analysis remains high, as it is constrained by the Fifth Circuit’s prior decision in Patterson.

/>i

/>i