Drug Manufacturers Prevail on Appeal in Challenges to HRSA’s Efforts to Limit Contract Pharmacy Conditions

The 340B Program exists to provide certain health care organizations, referred to as “covered entities,” with access to discounted outpatient drugs from manufacturers. Many covered entities, lacking their own pharmacies, enter into agreements with outside pharmacies, or “contract pharmacies,” to dispense 340B drugs to patients.

Since 2010, HRSA has maintained that a covered entity may engage an unlimited number of contract pharmacies to dispense 340B drugs, regardless of whether the covered entity has an in-house pharmacy. As the number of contract pharmacies has increased significantly since 2010, some manufacturers have imposed conditions on covered entities’ use of contract pharmacies, including limits on the number of contract pharmacies to which a manufacturer will ship 340B drugs. According to these manufacturers, such constraints are necessary to prevent diversion of 340B drugs to ineligible patients and duplicate discounts (i.e., discounts that are duplicative of rebate payments that manufacturers pay to state Medicaid programs for the same drugs) in violation of the 340B statute.

In response to these measures, the HHS Office of the General Counsel released an advisory opinion in December 2020, declaring that the 340B statute unambiguously requires drug manufacturers to deliver covered drugs to an unlimited number of contract pharmacies. Moreover, the HHS General Counsel concluded, a manufacturer must charge a covered entity that arranges with a contract pharmacy no more than the 340B “ceiling price,” which is the maximum amount, based on a statutory formula, that a manufacturer may charge a covered entity for an outpatient drug.

Several months later, HRSA began sending individualized enforcement letters to drug manufacturers that were not complying with its 2010 guidance. In those letters, HRSA contended that the requirement under the 340B statute for a manufacturer to offer a covered entity outpatient drugs at 340B ceiling prices was “not qualified, restricted, or dependent on how the covered entity chooses to distribute the covered outpatient drugs.” The agency demanded that the manufacturers immediately offer drugs at the 340B ceiling price to covered entities for dispensing through contract pharmacies, noting that continued noncompliance may result in civil monetary penalties.

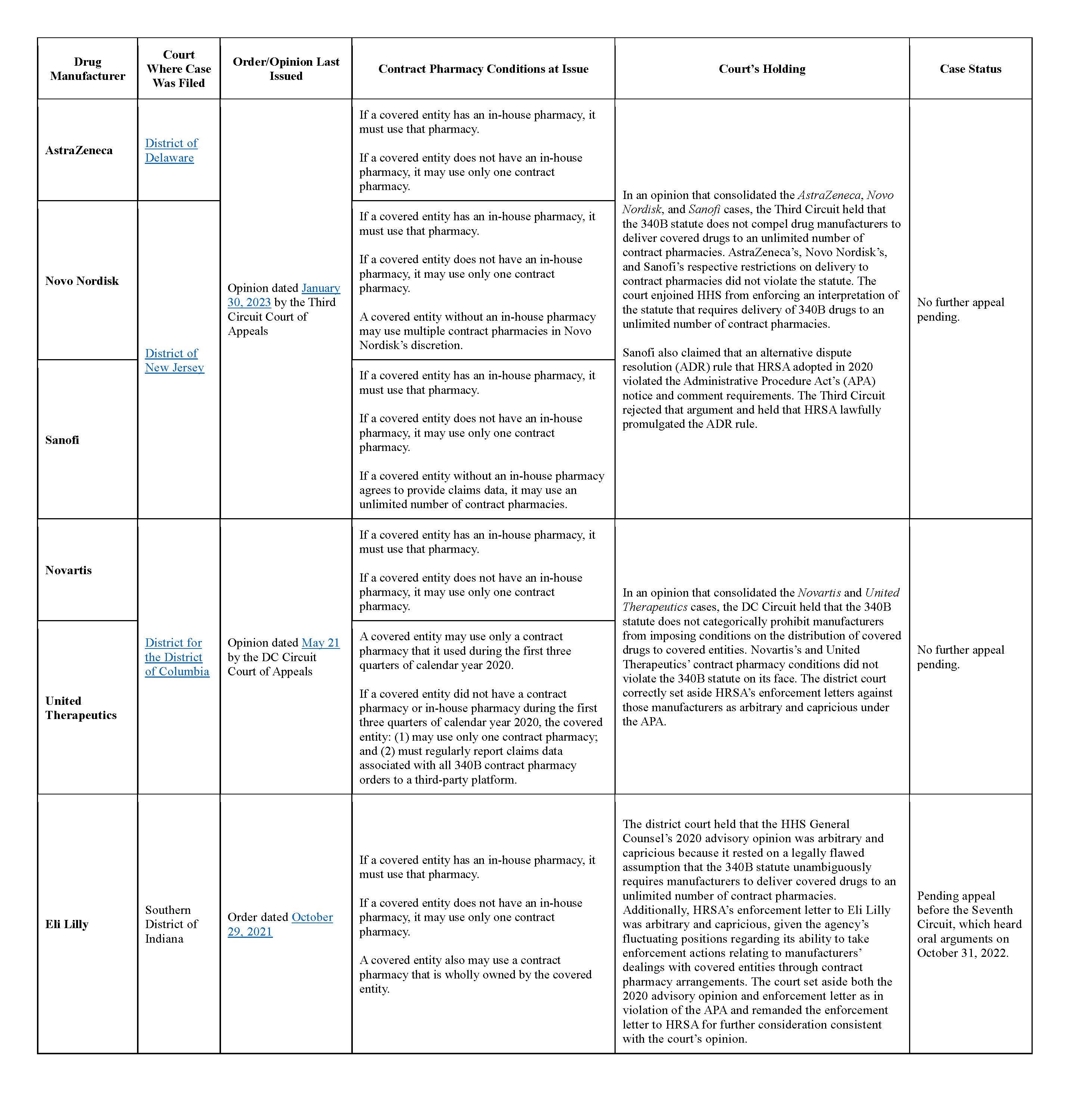

The 340B Saga officially commenced when six major drug manufacturers that received enforcement letters from HRSA — AstraZeneca, Eli Lily, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and United Therapeutics — initiated separate lawsuits against HRSA and other government parties in federal court. To date, two federal courts of appeals — the Third Circuit and, more recently, the DC Circuit — have weighed in on five of the cases. Ruling in favor of the manufacturers, both appeals courts concluded that the 340B statute does not prohibit a manufacturer from imposing conditions on a covered entity’s utilization of contract pharmacies.

Updates on each of these cases are in the chart below.

States Limit Contract Pharmacy Conditions but Face Legal Challenges

As drug manufacturers have put conditions on covered entities’ use of contract pharmacies, several states have intervened with the enactment of laws to prohibit manufacturers from engaging in such practices. This is a new twist in the 340B Saga since we published our prior alert.

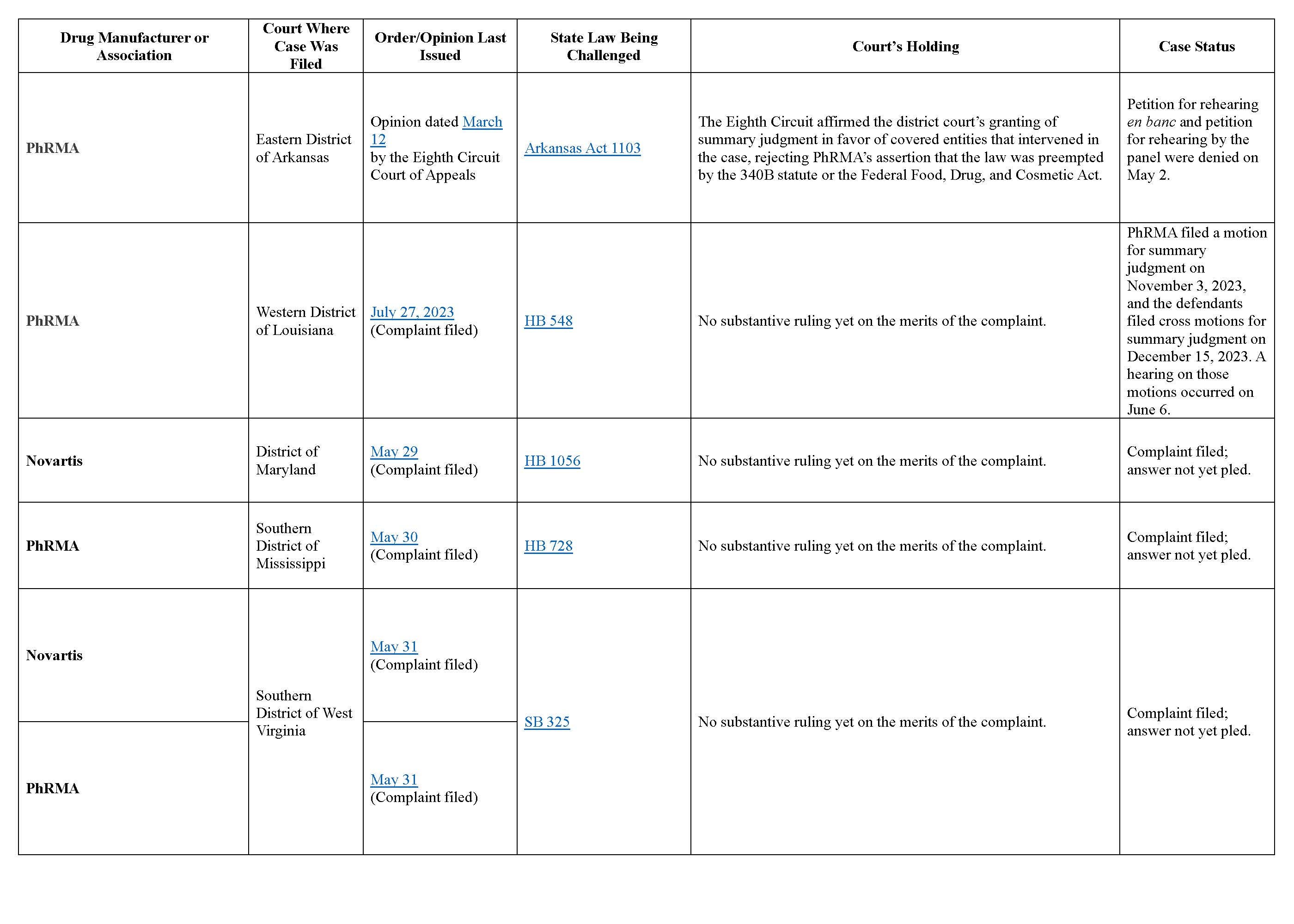

Like the HHS General Counsel’s 2020 advisory opinion and HRSA’s enforcement letters, these state laws have prompted legal challenges. Five states — Arkansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, and West Virginia — are all facing legal battles in federal court over their respective contract pharmacy laws. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), a trade association of drug manufacturers, is spearheading the challenges. At least one manufacturer (Novartis) has separately filed its own lawsuit to challenge one or more of the laws.

The main argument from these challengers is that the 340B statute overrides, or preempts, these state laws and renders them unconstitutional. The challengers also assert in some cases that the laws are unconstitutional because they are excessively vague or interfere with Congress’s authority to regulate interstate commerce.

Several of the cases are newly filed and have not yet produced any substantive rulings. To date, PhRMA’s suit challenging the Arkansas contract pharmacy statute is the only case that has undergone both district and appellate court review. In that case, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals held that neither the 340B statute nor the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act preempts the Arkansas law. In support for this conclusion, the court drew from the Third Circuit’s analysis in the consolidated AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi cases, noting that one may infer from the absence of any express terms in the 340B statute regarding the delivery of covered drugs that Congress did not intend to prevent states from regulating in this area.

More information on each case is in the chart below.

Stay Tuned as the 340B Saga Continues

The 340B Saga is hardly over. While the Third Circuit and DC Circuit reached similar conclusions that the 340B statute does not preclude a drug manufacturer from imposing conditions on a covered entity’s use of contract pharmacies, it remains to be seen how the Seventh Circuit will rule in the pending Eli Lilly case. If the Seventh Circuit’s decision conflicts with the other two circuit courts’ decisions, further resolution may require review by the US Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, more states are poised to adopt contract pharmacy protection bills, which are almost certain to invite more legal challenges. As in the other cases challenging HHS’s actions, Supreme Court review may be necessary if the appellate courts issue divergent opinions on whether federal law preempts state laws regulating contract pharmacy policies of drug manufacturers.

For now, the collective opinions of the Third, Eighth, and DC Circuits have created a curious regulatory environment where the states appear to have more robust authority than HRSA — the federal agency with oversight of the 340B Program — to curb drug manufacturers’ conditions on contract pharmacy arrangements. While manufacturers’ victories against HRSA in the Third Circuit and DC Circuit cases may embolden some manufacturers to rein in contract pharmacy utilization, they should recognize the risks that their actions may provoke complaints by covered entities and invite further state legislative proposals. Manufacturers’ contract pharmacy policies also may lead to further pressure on Congress to reform the 340B statute. We will be monitoring such policy developments and other dynamics, including the recently overhauled 340B ADR process, that may shape the future course of the 340B Saga.

Additional research and writing from Meredith Gillespie, a 2024 summer associate in ArentFox Schiff’s Washington, DC office and a law student at Wake Forest University School of Law.

/>i

/>i