When evaluating mergers, the law demands a balance: protecting competition while allowing efficiencies that benefit consumers. The proposed Union Pacific–Norfolk Southern merger, now before the Surface Transportation Board (STB), will test whether regulators can apply that balance in a fact-driven way.

Unlike most mergers reviewed by the Justice Department or Federal Trade Commission, railroads fall exclusively under the STB’s jurisdiction. Congress instructed the Board to approve rail consolidations if they serve the “public interest”—a standard broader than conventional antitrust tests. Competition matters, but so does service quality, safety, and system reliability. At the end of the day, however, the question is simple: will the merger benefit the public?

On the facts, the companies’ networks are complementary, not overlapping. Union Pacific covers the western and central corridors; Norfolk Southern is anchored in the east. Their lines rarely compete for the same customers. Rather than removing a rival, the merger would stitch together a seamless coast-to-coast system—America’s first truly transcontinental railroad.

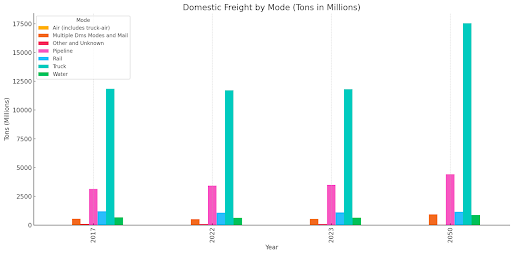

That matters because the real competitive challenge affecting transport by rail is not other railroads but trucking. For decades, long-haul trucking has gained market share at rail’s expense, aided by massive highway investments and the flexibility of trucks to serve any route. The result has been fewer choices for shippers and higher costs for consumers. Markets flourish when firms are free to compete across modes, each pressured to improve by the actions of the other.

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation Bureau of Transportation Statistics

By linking networks, the merged company could offer direct cross-country service without costly handoffs. That efficiency would force both rail and trucking to sharpen their offerings. Shippers would have more options, rates would reflect increased competition, and consumers would ultimately pay less. Many economists described competition as a “discovery process,” where entrepreneurs continually find ways to serve customers better. A Union Pacific-Norfolk Southern merger exemplifies this dynamic: it “discovers” a new way to deliver goods more efficiently across the entire continent. In other words, rail would finally become a real coast-to-coast shipping option.

Critics argue that size alone makes the deal suspect. However, the STB’s role is not to decide whether the merged entity looks “too big” but whether it advances consumer welfare. Here, scale means efficiency, and efficiency means downward pressure on shipping costs.

The STB’s “new rules,” adopted in 2001, require mergers to include provisions for “enhanced competition.” This merger does precisely that—not by pitting railroads against each other where overlap is minimal, but by enabling rail to better compete with trucking. Value is determined by consumers’ needs, not regulators’ abstractions. For shippers, that value lies in reliable, cost-effective service—and the merged system promises to deliver for the consumer.

Overregulation or reflexive opposition to mergers risks dulling the very forces that make markets work. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek cautioned against the hubris of central planning, where authorities impose their preferred structures instead of letting rivalry and discovery run their course. The STB should heed that warning. This merger is not about protecting incumbents; it is about empowering competition between modes of transport, giving shippers more leverage, and driving costs down for consumers.

The statutory framework does not ask whether a merger is politically popular or ideologically comfortable. It asks whether the merger serves the public interest. By broadening options, strengthening rail–truck competition, and lowering costs, the Union Pacific–Norfolk Southern merger does exactly that.

All of the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of The National Law Review.

/>i

/>i