In Lawson v. Spirit AeroSystems, Inc., the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit upheld the forfeiture of certain stock awards for violating a covenant not to compete. Like the Seventh Circuit in LKQ Corp. v. Rutledge(which applied Delaware law), the Tenth Circuit concluded that, under Kansas law, the remedy of forfeiting future compensation is not subject to the same reasonableness standard as traditional enforcement of a non-compete obligation. The Tenth Circuit reached this conclusion even though the executive’s agreement included both a forfeiture-for-competition provision and traditional enforcement rights (i.e., the right for the company to pursue monetary damages and specific performance), because the agreement terms enabled the forfeiture provision to be severed from the traditional enforcement provisions.

Background and the Court’s Analysis

A retirement agreement allowed the former CEO of Spirit AeroSystems (“Spirit”) to receive cash payments and continue vesting in certain stock awards if he continued working for Spirit as a consultant and complied with a non-compete agreement. The CEO subsequently contracted with a hedge fund that was pursuing a proxy contest against one of Spirit’s suppliers. Spirit determined that this activity breached the non-compete and therefore stopped payments to the CEO and cut off continued vesting of the stock, resulting in forfeiture of the CEO’s then-unvested stock awards. Notably, Spirit did not seek to claw back cash that had already been paid or stock that had already vested: only future compensation and vesting were affected.

The court first found under Kansas case law a distinction between a traditional penalty for competition and forfeiture of future compensation for competition. Under Kansas case law, the former is valid and enforceable only if “reasonable under the circumstances and not adverse to the public welfare.” But the court concluded that Kansas law does not subject the latter to the same reasonableness standard because it does not restrain competition in the same way. Rather than imposing a penalty, a forfeiture for competition provision “merely provides a monetary incentive in the form of future benefits for not competing.” The court reasoned that a forfeiture for competition provision gives the worker “a choice between competing and thereby forgoing the future benefits or not competing and receiving those benefits.” And because the forfeiture applied only to future compensation, it did not amount to a penalty: the executive forfeited only “the opportunity for the shares to vest notwithstanding his retirement.”

Second, the court reasoned that the policy justifications for reasonableness review did not apply to forfeiture in this case. The court stated that reasonableness review addresses the risk that (1) the employer’s bargaining power can lead to a one-sided non-compete that leaves former employees unable to support themselves after their employment ends and (2) “overbroad” restrictions on competition can “decrease options available to consumers and generate market inefficiencies.” The court concluded that neither of those risks were present in this case, noting that the executive was sophisticated and had support of counsel and that the executive had an opportunity to receive substantial compensation if he had complied with the covenant.

Third, the court reasoned that “[f]reedom of contract is the fountainhead of Kansas contract law.” Accordingly, the court determined that the forfeiture-for-competition provision should be presumed enforceable, absent the policy concerns described above.

Unlike the Seventh Circuit in LKQ—which certified a question of Delaware law to the Delaware Supreme Court—the Tenth Circuit refused to certify the question of Kansas law to the Kansas Supreme Court. For the reasons described above, the court determined that it could predict the Kansas Supreme Court’s interpretation of Kansas law with sufficient confidence to make certification unnecessary.

Finally, the court rejected an argument that reasonableness review should be required because Spirit had both the right to invoke forfeiture and the right to seek traditional enforcement (monetary damages and specific performance). The court determined that, in this case, the right to seek traditional enforcement could be severed from the right to invoke forfeiture. Because Spirit relied exclusively on the forfeiture provision and expressly declined to pursue traditional enforcement, the fact that Spirit could have pursued traditional enforcement was not fatal.

Takeaways

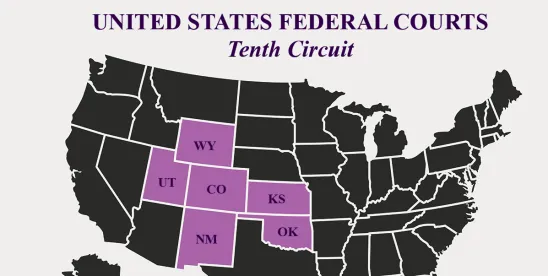

Although Lawson is binding only on federal courts in the Tenth Circuit that are applying Kansas state law (and Kansas state courts could still reach a different conclusion), it provides meaningful authority for the proposition that a forfeiture for competition provision can be enforced even if applicable law otherwise limits the enforceability of non-compete provisions. (Notably, however, some states reject forfeiture for competition.) The decision offers a few important practical takeaways:

- The particular facts matter. In this case, the court noted that the forfeiture provision had been negotiated by sophisticated parties represented by counsel and determined that policy concerns with non-compete provisions (interfering with the ability to make a living and potential to generate market inefficiencies) were not present.

- Drafting matters. If an agreement has more than one enforcement mechanism (e.g., a right to seek damages and injunctive relief and a separate statement that breach will result in forfeiture of certain compensation or benefits), it is important to make each enforcement mechanism distinct and severable from the others. The result of this case could have been different if the agreement did not have a severability clause. It also helps to state clearly that amounts subject to forfeiture are not considered earned or fully vested (even if considered vested for tax purposes) unless and until the employee has satisfied all applicable conditions. Clarity on this point helps the court to distinguish between a permissible compensatory incentive to comply and a potentially impermissible penalty for breach.

- Enforcement strategy matters. The court emphasized that Spirit did not pursue injunctive relief or damages and that the forfeiture applied only with respect to future payments and vesting. Had Spirit sought to claw back prior payments or stock that had already vested, the court might have treated the forfeiture as a penalty that required reasonableness review.

/>i

/>i