On May 18, 2023, the US Supreme Court affirmed the Second Circuit’s decision that artist Andy Warhol’s silkscreen portrait of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of musician Prince, used for a Vanity Fair cover, was not a fair use under US Copyright Law.

In a 7-2 decision, the Court found the “purpose and character” factor of the copyright fair use analysis did not weigh in favor of a finding of fair use where the use of a new work encompassing an original work shares the same purpose as the use of the original work and is commercially licensed.

Although the addition of a new meaning or message is a relevant consideration in assessing the purpose and use of a work for purposes of determining fair use, it is not dispositive. According to the Court, the “purpose and character” fair use factor must consider “the reasons for, and nature of, the copier’s use of an original work,” balanced against the original creator’s exclusive right to make derivative works. If the new work achieves the same or similar purpose to the original work, and the new use is of a commercial nature, the first fair use factor likely weighs against a finding of fair use, absent another justification of copying. Ultimately, the inquiry is objective and questions how the original user has used the original work.

The case comes with much anticipation and could have significant implications on the availability of the “fair use” defense in copyright infringement cases, including potentially with respect to the hotly contested use of generative artificial intelligence to create new works.

Background

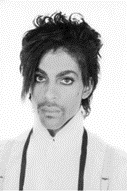

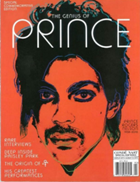

Vanity Fair magazine originally commissioned Warhol to create an image of Prince for publication alongside an article of the musician in 1984. Photographer Lynn Goldsmith granted the magazine a “one time” license for it to use one of her Prince photographs as an “artist reference for an illustration.” Warhol created a purple silkscreen portrait using Goldsmith’s photograph. The magazine credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph” and paid her $400.

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, Warhol created 15 other silkscreen prints and pencil drawings from Goldsmith’s same image of Prince. Goldsmith claimed she did not learn of the Prince series until 2016, when Condé Nast published some of the images in a posthumous tribute to Prince. In particular, in 2016, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF) licensed an “Orange Prince” silkscreen image to the magazine for $10,000 for its cover. Goldsmith did not receive any compensation or credit.

Goldsmith’s Photograph Warhol Illustration

|

|

|

In response to Goldsmith’s objections, AWF sued for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement of Goldsmith’s alleged copyright. Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement. On Goldsmith’s counterclaim, the district court granted summary judgment for AWF, finding all four copyright fair use factors, under 17 U.S.C. §107, weighed in the foundation’s favor. The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit however reversed and remanded, finding all fair use factors favored Goldsmith.

Decision

The only issue before the Supreme Court was whether the “purpose and character of the use” weighed in favor of AWF such that its commercial licensing to Condé Nast would be considered fair use. The Court ultimately agreed with the Second Circuit, finding in favor of Goldsmith, and that the factor did not favor AWF’s fair use defense to copyright infringement.

Goldsmith had licensed her works for years, with images appearing in Life, Time, and Rolling Stone magazines. People magazine had also paid Goldsmith to use one of her Prince images in a special collector’s edition of its publication following Prince’s death. Because Goldsmith’s original photograph and AWF’s work licensed to Condé Nast were both portraits of Prince, “used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince[,]” the Court found the works had the same purpose and that AWF’s use did not favor a finding of fair use.

A determination of fair use requires consideration of the following four factors set forth in §107 of the Copyright Act:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- The nature of the copyrighted work;

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The Court explained that the central question in determining the first fair use factor asks whether and to what extent the new use adds something new, with a further purpose or different character. The larger the work supersedes the objects of the original creation and goes beyond that required to qualify as a derivative work, the more likely the purpose and use factor will weigh in favor of a finding of fair use. Works that merely supersede the objects in the original creation — without adding something new, with a different character or further purpose — are unlikely to be found transformative and thus fair.

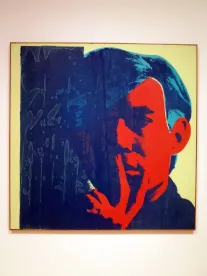

Included in the Court’s fair use analysis was significant discussion of its 1994 Campbell decision, a case involving 2 Live Crew’s copying of Roy Orbison’s song, “Oh, Pretty Woman,” and from which it created a rap derivative, “Pretty Woman.” There, the Court found the new work clearly transformative in that it was a parody, had a different message and aesthetic, and had the distinct purpose of commenting on the original.

Conversely, Warhol’s image was substantially the same as Goldsmith’s original photograph in that both were used to illustrate a portrait of Prince, AWF received compensation for doing so, and the degree of difference (i.e., the flattening, tracing, and coloring of the photo) was not enough for the first factor to favor AWF, according to the Court.

The Court compared AWF to other would-be users who may attempt to seek the shelter of the fair use defense, including musicians who sample songs, playwrights who adapt novels, and filmmakers who create spinoffs, noting that a finding of fair use in the case might authorize a range of commercial copying for use in a substantially same manner as the original work.

Takeaways

- Depending on the ultimate use, it may be harder for visual artists (or even generative AI applications) who appropriate content without licenses to defeat infringement claims with fair use defenses.

- Whether a work is transformative is a matter of degree. An owner has an exclusive right to create derivative works, and such transformations may be substantial. To qualify as transformative, the new use must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative work.

- All fair use factors must be explored, and the results weighted together, even if a work is found to be transformative.

- The commercial nature of a use is not dispositive; it must be weighed against the degree to which the use has a different character or further purpose from the original use.

/>i

/>i