Investigators routinely disregarded rules while rejecting complaints of reprisals for reporting waste, fraud and abuse

The Defense Department has inadequately protected from reprisals whistleblowers who have reported wrongdoing, according to an internal Pentagon report, and critics are calling for action to be taken against those who have been negligent. The report, dated May 2011, accuses the officials, who work in the Defense Department’s Office of Inspector General, of persistent sloppiness and a systematic disregard for Pentagon rules meant to protect those who report fraud, abuses, and the waste of taxpayer funds, according to a previously-undisclosed copy. The report was obtained by the Project on Government Oversight, a nonprofit watchdog group.

A three-person team of veteran investigators at the Pentagon, assigned to review the performance of the “Directorate of Military Reprisal Investigations,” concluded in the report that in 2010 the directorate repeatedly turned aside evidence of serious punishments inflicted on those who had complained.

The actions included threatened or actual discharges, demotions, firings, prosecutions, and even a mental health referral. At least one of the alleged reprisals was taken because the complainer had written to Congress, an act that Pentagon regulations say is a “protected communication” immune from retaliation. Some of the other whistleblowers had alleged discrimination, travel violations, and “criminality,” the report states.

In all, the team disputed the directorate’s dismissal of more than half of the 156 whistleblowing cases it reviewed and called for the directorate to revamp its procedures and start enforcing the protective rules.

“This devastating report proves one of our worst fears — that military whistleblowers have systematically been getting a raw deal,” said Danielle Brian, executive director of the Project on Government Oversight. Her group obtained the report

Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa.), the Judiciary Committee’s top Republican, similarly called it disturbing that the directorate had bungled so many cases. “Heads must roll,” he said in an April 24 letter to Acting Inspector General Lynne M. Halbrooks after reading a copy of the report. “The root cause problems identified in the report must be addressed and resolved immediately.”

The creation of the reprisal investigations unit grew out of hearings and legislation in the 1990s that spotlighted the military’s practice of ordering mental health evaluations for whistleblowers, a move that hindered their careers. The office, which is expanding this year from 31 to 51 employees, is responsible for investigating or overseeing the handling of hundreds of complaints of retaliation annually — those made directly by troops and Pentagon employees to the IG, and those made to the military services.

Under federal law, prohibited reprisals are adverse actions taken in response to protected disclosures, which involve reports of violations of laws, rules, and regulations, gross mismanagement, abuses of authority, and dangers to health and safety. The reprisal investigator’s work is, according to an Oct. 2011 memo by the Defense Department’s deputy inspector general Marguerite C. Garrison, “essential to preventing fraud and abuse — and to promoting economy and efficiency” in the $677 billion national defense budget.

In response to the report, Garrison last year reorganized the office and began an overhaul of its manual. She also imposed a rule that prima facie evidence of retribution should provoke a preliminary inquiry in all cases. “The lessons learned … have proved vital to establishing more robust policies and procedures,” said Bridget Ann Serchak, the chief spokesman for Acting Inspector General Lynne M. Halbrooks.

Independent experts and whistleblower advocates remain skeptical, however. Reports going back a decade have criticized the Inspector General’s office for poorly tolerating whistleblowers; a group of Pentagon-paid outside consultants said in 2002 that even those inside the office who complained of mismanagement were “punished by their chain of command” amid a culture that was hostile to any form of whistleblowing.

In February, a report by the Government Accountability Office said that the reprisal investigators routinely took too long to respond to complaints, exceeding a 180-day deadline 70 percent of the time; the mean processing time was instead 451 days. It also said that investigators frequently used unreliable and incomplete data and case files, and concluded that only 5 percent of closed case files were actually “complete.” Records of testimony by complainants were missing from more than half of the files studied.

Critics have also complained that most allegations of misconduct are simply turned aside by the reprisal investigations office, often without any investigation.

“DODIG closed most complaints before conducting a full investigation and writing the resulting report of investigation,” the GAO said in its February report, adding that the office’s instructions to investigators remained “outdated” or “unclear.” According to Grassley, the GAO made “regular monthly requests” last year for the May 2011 internal review by the three investigators, but was refused a full copy for seven months.

“This report helps to confirm what everyone knew in practice — that the IG has not respected the law’s mandate,” says Tom Devine, legal director for the Government Accountability Project, a nonprofit advocacy group that has represented Pentagon employees in lawsuits challenging alleged reprisals. He said the IG’s office — created in part as a refuge of last resort for those whose complaints of wrongdoing are ignored by others — has often been “a Trojan horse,” whose agents are “hatchetmen for agency managers” looking for the smallest infraction to punish their whistleblowers.

The internal reviewers said the office wrongly dismissed complaints by personnel threatened with punitive action on the sole grounds that those actions had not yet been carried out. It also wrongly dismissed cases in which letters of reprimand, counseling or instruction were written against whistleblowers but not placed in permanent files — on the grounds that such “locally held” letters were not “unfavorable personnel actions.”

The reviewers said these decisions were clearly contrary to a provision of the U.S. Military Whistleblower Protection Act of 1988, which bars officers or other superiors from either taking or threatening to take unfavorable actions.

“In some of the cases the Team reviewed, members were threatened with negative fitness reports, termination, and court-martial proceedings. Rather than allow the complaint to proceed to the next stage in the process, the reprisal investigators instructed the member that if the action occurs, they could file their complaint again, and thus declined the complaint,” the report said. “These cases should not have been declined.”

The reviewers also said that when the office routinely ignored locally held “letters” that threatened discharge, reassignment, lower pay, or any other change in duties it violated “the plain language” of a 2007 Defense Department order meant to insulate whistleblowers from retaliation. In one instance, investigators wrongly closed a case in which a complainant was denied a NATO job solely on the basis of such a letter; in another case, they wrongly closed a case in which a complainant was forcibly transferred to another unit.

Most details of the whistleblowing complaints, as well as the names of the complainers and the investigators who rejected their cases, were not included in the report. Serchak said that information was protected under the Privacy Act and statutes governing the Inspector General.

But an appendix to the report states that someone whose “protected communication” was a letter to Congress was demoted and had “separation paperwork” prepared. The reprisal investigators nonetheless closed the case on grounds that there was insufficient documentation, a decision that the review team disputed.

One case was closed on grounds that the complainant’s punishment was unrelated to his allegations of wrongdoing, even though an officer had acknowledged it was done in retaliation and the file included a quoted warning to “follow your chain of command or pay the price.” In another case, “bias was found, but not addressed;” in still another, the team said an “allegation of criminality should have been reported/referred.”

In all, the team disputed the office’s decisions to turn aside 82 of the 156 cases in the random sample it reviewed from fiscal year 2010, or 52.6 percent. The widest gap (68 percent) occurred in cases that the office simply refused to open; smaller gaps occurred in cases where some preliminary work was conducted before the cases were shut, and when a full investigation was completed before the allegation was rejected.

In some cases, according to the report, the team disagreed because the files collected by the office simply lacked enough information to decide one way or the other. “The Team thinks that many of the cases would not have been substantiated,” their report said, but there was no way to know.

Fifteen cases — including one in which a soldier was deployed to an active combat zone — were declined by reprisal investigators because the claimant did not provide enough evidence, according to the report. The team said this “appears to be contrary to the intent of the statute and DoD policy” to give whistleblowers the benefit of the doubt in such instances.

In 27 cases, the reprisal investigators declined to open a full probe without first obtaining a statement from the manager accused of retaliating — as Pentagon rules require. Instead, the manager’s intent was assumed, according to the report.

Senator Grassley, in his April 24 letter to acting Inspector General Halbrooks, said the internal report “appears to suggest that OIG officials knowingly ignored the law and showed disrespect for military whistleblowers and the core IG mission.” He asked that Halbrooks tell him whether “supervisors and managers [were] subjected to administrative review or other corrective actions for their failure to adhere” to the rules and regulations.

He also asked that all the cases that the review concluded were wrongly turned aside be reexamined and that the personnel who alleged punishment be told “that their complaints were mishandled.”

Pentagon spokesmen declined to allow reporters access to Jane Deese, the head of the reprisal investigations office at the time of the review. She currently heads the Inspector General’s Office of Professional Responsibility, responsible for reviewing the operations of each component of the office and assessing its “managerial, operational, and administrative efficiency and effectiveness” — akin to being a watchdog of sorts for the Pentagon’s watchdog.

Halbrooks responded in an April 26 letter to Grassley that the reprisal investigations office now has new leadership; its current director is Nilgun Tolek, the former head of whistleblower complaints with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. But Halbrooks added that “I strongly disagree with the assertion” that IG officials knowingly ignored the law. “I stand behind the continued professionalism and dedication of our reprisal investigators, past and present,” she said.

Halbrooks said she would respond to Grassley’s questions in person, not in writing. In response to similar questions from the Center for Public Integrity, Serchak said initially her office decided that the cases of concern “were decided on the basis of the DOD IG policy in place at the time. After further consideration, however, we are now reviewing some of the cases.”

Serchak also did not respond to a question about sanctions for those who had bungled cases, saying that since the report identified “systemic issues … we implemented new policies and procedures to … transform it into a model program.”

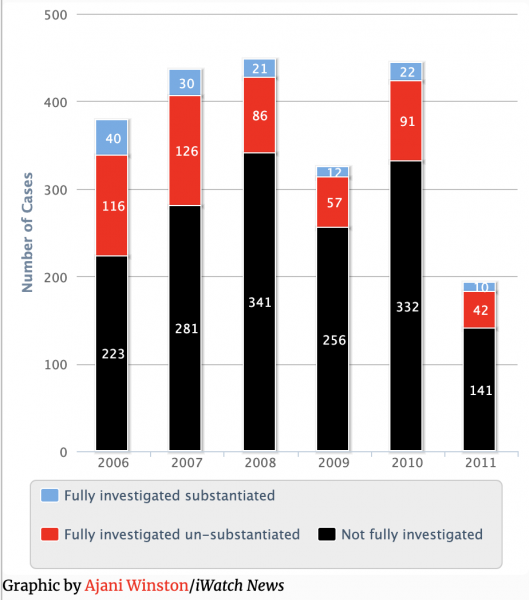

Reprisal outcome for whistleblower complaints: 2006-2011

The Pentagon's reprisal investigations office over the past six years affirmed only a small percentage of the claims made by civilians and military personnel that they had been punished for making protected disclosures of inappropriate conduct by their units or superiors. Most cases were never fully investigated.

Graphic by Ajani Winston/iWatch News

/>i

/>i