With almost all of the current news being focused on coronavirus-related topics, it’s easy to forget that courts and agencies continue to do their jobs, issuing decisions and opinions. On occasion, one of those decisions is significant enough to warrant a distraction from all things COVID-19. A recent National Labor Relations Board (NLRB or Board) decision is one such instance.

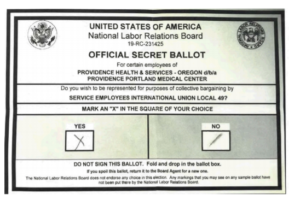

One of the functions of the NLRB is to oversee representation case elections, which are elections conducted to determine whether employees wish to be represented by a labor union. These elections are conducted using traditional paper ballots marked by employees by hand with a pencil or pen. The ballots are hardly complicated; they ask a single question regarding the employee’s union-representation preference, requiring only that an employee make a mark in a box labeled “Yes” if he or she desires union representation, or make a mark in a box labeled “No” if not.

Seems simple enough, right? On occasion, however, employees do more than just place a mark in the “Yes” or “No” box. Sometimes marks appear in both boxes, such as when an employee checks one box and then attempts to erase or change their vote to the other box.

Under NLRB precedent, ballots with stray or extra marks were deemed void unless the intention of the voter could be determined from the face of the ballot. So, for example, if it was clear that an employee started to make an “X” in one box, then clearly attempted to erase or cross-out that mark, and then placed a clear, unerased “X” or similar mark in the other box, the ballot would be counted.

In its May 13, 2020 decision in Providence Health & Services-Oregon d/b/a Providence Portland Medical Center, the Board was confronted with exactly this sort of dual-marked ballot issue. Although one ballot typically does not determine the outcome of an election, in this particular case, the stray-marked ballot was the determinative vote (in an election involving almost 800 ballots). The ballot at issue was marked like this:

An administrative law judge determined that the voter casting this ballot clearly intended to vote “Yes,” and that the fuzzy single line in the “No” box reflected an obvious attempt to erase an incomplete “X” in the “No” box. Accordingly, the judge determined, and the NLRB Regional Director adopted his conclusion, that that the ballot should not be voided, and instead should be counted as a vote in favor of union representation – the result of which would mean that the union won the election.

On appeal, the NLRB took issue with the then-current standard, which requires that the Board attempt to determine the intent of the voter when confronted with a ballot containing dual or stray marks. The Board explained that existing precedent on the issue of dual-marked ballots was “convoluted, difficult to apply, and unreliable as a means to divine voter intent.” To eliminate this uncertainty, the NLRB announced a new, bright-line rule, stating:

…we now hold that where a ballot includes markings in more than one square or box, it is void. We overrule any cases in conflict with this principle. This bright-line approach will spare the Board from engaging in necessarily speculative inquiries to ascertain voter intent, and will also preserve Board and party resources by applying a clear, objective standard that will avoid the litigation that has accompanied the Board’s prior approach to dual-marked ballots. This new approach will also permit the Board to more expeditiously certify election results and define parties’ respective rights and duties.

So there you have it. The legal unicorn – a simple, straightforward rule – that eliminates the need to attempt to figure out what a voter intended by making extra marks on a ballot. Going forward, any ballot that contains any marks other than a mark in either the “Yes” or “No” box is void and will not be counted. Applying its new rule to the case before it, the Board voided the dual-marked ballot, which left the vote count tied at 383 to 383. Because a union must obtain a majority of the votes cast to win a representation case election, the tie here meant that the union lost the election.

/>i

/>i