In 2018, actress Ashley Judd (“Judd”) sued producer Harvey Weinstein (“Weinstein”) for sexual harassment, defamation, intentional interference with prospective economic advantage, and unfair competition. Judd alleges that during a meeting with Weinstein to discuss casting opportunities, she was directed to his hotel room where he appeared in a bathrobe and tried to coerce her into massaging him and watching him shower. See Judd v. Weinstein, No. 2:18-cv-05724-PSG-FFM (C.D. Cal 2018). After she refused his overtures, Weinstein allegedly defamed Judd by adversely commenting on her professionalism to prominent directors and others in the industry, which hurt Judd’s career opportunities.

Enacted in 1994, California Civil Code Section 51.9 establishes a civil cause of action for sexual harassment in non-employment relationships. It covers “business, service, and professional relationships” such as those a person might have with a physician, psychotherapist, dentist, attorney, social worker, real estate agent, real estate appraiser, investor, accountant, banker, trust officer, financial planner, collection service, building contractor, escrow loan officer, executor, trustee, or administrator, landlord or property manager, teacher and any substantially similar relationship. Largely in response to the #MeToo movement, the California legislature amended the statute in 2018 to include “investor, elected official, lobbyist, and director or producer” to the list of covered relationships.

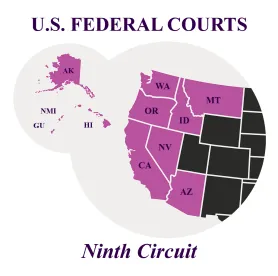

Finding that Judd’s relationship with Weinstein was not covered by the prior version of Section 51.9 and that the 2018 amendment was not retroactive, the trial court dismissed Judd’s sexual harassment claim. See Judd v. Weinstein, 2019 WL 926343, at *4-8 (C.D. Cal. 2019). Judd appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. During oral argument before the Ninth Circuit on May 8, 2020, Judd’s attorney argued that Section 51.9 applied even without the amendment involving “director or producer” because it covered “business, service, or professional relationships,” which described Judd and Weinstein’s association in late 1996 or early 1997. Weinstein’s attorney countered that Judd did not have a professional relationship with his client at the time of the alleged hotel meeting and that the “directors and producers” wording of the statute could not be applied retroactively.

On July 29, 2020, the Ninth Circuit reversed the district court’s dismissal of Judd’s sexual harassment claim. The panel held “section 51.9 plainly encompassed Judd and Weinstein’s relationship” at the time of the alleged harassment. See Judd v. Weinstein, No. 19-55499, 2020 WL 4343738, at *6 (9th Cir. 2020). The court further held that “their relationship consisted of an inherent power imbalance wherein Weinstein was uniquely situated to exercise coercion or leverage over Judd by virtue of his professional position and influence as a top producer in Hollywood.” The court also held that “whether Judd and Weinstein’s relationship was in fact an employment relationship outside the purview of section 51.9 was a question for the trier of fact” and remanded for further proceedings.

This is just the latest example we’ve seen of a sexual harassment claim related to an alleged power differential that existed outside the employment setting.

/>i

/>i