On 8 May 2017 the High Court in London applied a strict approach to litigation privilege in the context of self-reporting investigations. It is the first case in which a court has considered whether litigation privilege is engaged in a criminal investigation involving the UK Serious Fraud Office (“SFO”). This decision is likely to have significant consequences on the conduct of corporate internal investigations in a civil and criminal context and on self-reporting in the criminal context, including cross-border investigations. This memo considers the current UK position on legal professional privilege, placing the recent decision of the High Court in the context of previous key decisions on privilege, Three Rivers (No. 5)[1] and the RBS Rights Issue Litigation[2] (“RBS”).

Background

In 2011, Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (“ENRC”)[3] agreed with the SFO to undertake a self-reporting investigation using external lawyers in relation to allegations of bribery, cross-border corruption and fraud involving its Kazakhstan and African businesses. The investigation was conducted by Dechert LLP and involved a significant number of witness interviews, evidence collection and analysis. In April 2013 the SFO commenced its own formal investigation.

As part of the investigation, the SFO issued notices against various entities and individuals, including ENRC, to compel the production of documents, pursuant to its powers under section 2(3) of the Criminal Justice Act 1987. This power does not extend to compulsion of the production of documents which a person “would be entitled to refuse to disclose or produce on grounds of legal professional privilege in proceedings in the High Court”.[4] ENRC refused to hand over certain documents generated during the self-reporting investigation, claiming that these documents were subject to legal professional privilege. The SFO sought a declaration from the Court that the Disputed Documents were not subject to legal professional privilege. The Court’s Judgment was released on 8 May 2017, in The Director of the Serious Fraud Office v Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation Ltd[5] ( the “ENRC Decision”).

The Disputed Documents

The disputed documents fell into four categories. The first consisted of notes taken by lawyers at Dechert LLP of interviews of employees and former employees of ENRC and its subsidiaries, their suppliers, and other third parties. The claim in relation to this first category of documents only concerned whether litigation privilege applied.

The second category concerned materials generated by forensic accountants as part of “books and records” reviews they carried out in London, Zurich, Kazakhstan and Africa, looking at identifying controls and systems’ weaknesses and potential improvements. The claim in relation to this second category of documents only concerned whether litigation privilege applied.

The third category consisted of documents indicating or containing the factual evidence presented by the partner at Dechert who had conduct of the investigations at all material times and reported to ENRC’s Nomination and Corporate Governance Committee and/or the ENRC Board in 2013. ENRC claimed legal advice privilege over these documents, and in the alternative, litigation privilege.

The fourth category of documents concerned documents provided to Fulcrum Chambers, who succeeded Dechert as ENRC’s legal advisors. Some of these documents included the second category forensic reports and emails and letters enclosing the same. ENRC claimed litigation privilege in the same way it claimed it applied to the second category of documents. There were also two emails between a senior ENRC executive and an ENRC employee who was a qualified Swiss lawyer, head of the mergers-and-acquisitions team, and the previous General Counsel. ENRC claimed legal advice privilege over these emails.

Litigation Privilege

Litigation privilege will apply to communications or documents where the following conditions are satisfied:

- litigation must be in progress or reasonably in contemplation;

- communications or documents must be made with the sole or dominant purpose of conducting the anticipated litigation; and

- the litigation must be adversarial, not investigative or inquisitorial[6].

When is litigation reasonably in contemplation?

The question of when litigation is ‘reasonably in contemplation’ can be a difficult question to answer, and will depend on the facts of the case. There must be more than a general apprehension or distinct probability, but litigation need not be more likely than not to occur.[7]

The ENRC Decision is the first case to consider this issue in the context of a criminal investigation. The Court held that the claim for litigation privilege failed at this first hurdle. While it accepted that at the relevant point in time ENRC anticipated that an SFO investigation was imminent, it rejected the submission that a criminal investigation by the SFO should itself be treated as adversarial litigation.

The Court also rejected the alternative submission that once a criminal investigation by the SFO was contemplated, so too was a criminal prosecution, noting that:

“It is always possible that a prosecution might ensue, depending on what the investigation uncovers; but unless the person who anticipates the investigation is aware of circumstances that, once discovered, make a prosecution likely, it cannot be established that just because there is a real risk of an investigation, there is also a real risk of prosecution.”[8]

The court went on to observe that “prosecution only becomes a real prospect once it is discovered that there is some truth in the accusations, or at the very least that there is some material to support the allegations of corrupt practices.”[9]

Prior to the ENRC Decision, the only other real consideration of when privilege may arise in the context of an investigation was that found in Tesco Stores Ltd v OFT[10] (“Tesco Stores”). In that decision, notes of discussions between Tesco and/or its external solicitors and potential witnesses made during an investigation conducted by the Office of Fair Trading (“OFT”) under the Competition Act 1998 were held to attract litigation privilege. This was because at the time of these interviews, the OFT’s investigation was “sufficiently adversarial” such that it constituted litigation. In determining that the OFT investigation was sufficiently adversarial at the time the potential witnesses were contacted, the Tribunal considered it relevant that the OFT had issued notices proposing to find an infringement. The Tribunal distinguished the situation which was before it from that of an inquiry designed only to ascertain the true facts of a situation. Both the ENRC Decision and Tesco Stores turned on their facts, yet the approach adopted is consistent – an investigation is not, in itself, sufficient justification for litigation privilege to arise.

Civil versus criminal litigation

Following the ENRC Decision, whether any eventual proceedings are likely to be civil or criminal may also impact on whether litigation is considered “likely”. The Court noted that a key distinction between civil and criminal litigation is that civil proceedings can be brought even if there is no foundation to them. This means that a person may have reasonable grounds to believe that it will be subject to civil litigation, despite there being no properly arguable cause of action, or a lack of evidence at that point in time to support such a claim. In contrast, the Court considered that “[c]riminal proceedings cannot be reasonably contemplated unless the prospective defendant knows enough about what the investigation is likely to unearth, or has unearthed, to appreciate that it is realistic to expect a prosecutor to be satisfied that it has enough material to stand a good chance of securing a conviction.”

It may therefore be more difficult to establish that litigation privilege arises when the potential proceedings are criminal, rather than civil, in nature, although this will ultimately depend on the facts of a specific case.

Made for the purpose of conducting the litigation.

The Court expressly rejected the contention that third-party documents created in order to obtain legal advice as to how best to avoid contemplated litigation (even if that entails seeking to settle the dispute before proceedings are issued), are covered by litigation privilege.[11] The Court saw this as undermining the rationale for litigation privilege, drawing a distinction between a party equipping itself to conduct its defence, and equipping itself with evidence that it hopes will persuade someone not to commence proceedings in the first place.

On the evidence, the Court was not satisfied that the information being gathered by ENRC’s legal advisors or forensic accountants as part of the self reporting investigation was for the conduct of future contemplated litigation. Initially, ENRC’s internal investigations were made in preparation for an anticipated investigation by a regulator or other investigatory body. Even if ENRC’s investigation was aimed at minimising the risk of an investigation by the SFO, the Court held that “avoidance of a criminal investigation cannot be equated with the conduct of a defence to a criminal prosecution,”[12] and as such, litigation privilege would not apply.

The Court also considered documents created during the self-reporting phase of the investigation. While recognising that, in theory, documents could be created for the purpose of persuading the SFO not to prosecute but also, if that failed, to help it mount a defence, the Court was not satisfied on the evidence that any documents had been created for this purpose. In fact, almost all the information generated was intended to be shared with the SFO, with the dominant purpose being to enable reports and presentations to be made to the SFO. It could therefore not be treated as subject to litigation privilege.

Legal Advice Privilege

Legal advice privilege will apply to confidential communications and documents made between a lawyer and his/her client, provided that the communication was made for the purpose of giving or receiving legal advice.

Who is the client for the purpose of legal advice privilege?

In Three Rivers (No. 5), the Court of Appeal applied a narrow approach to who is the “client” for the purposes of legal advice privilege. This narrow approach was applied recently by the High Court in RBS and now most recently in the ENRC Decision and reflects the current state of the law in respect of legal advice privilege. In Three Rivers (No. 5), the Bank of England had established a committee to communicate with the Bank’s appointed external lawyers in relation to a public inquiry. The Court of Appeal held that privilege only protected communications or draft communications between the committee and the external lawyers, and any documents or communications prepared by non-committee employees or officers of the bank were not so protected, even if they were prepared so that the lawyers could provide legal advice.[13]

In RBS the Court found that notes of interviews taken by solicitors of the Royal Bank of Scotland with its employees and former employees for the purpose of enabling the bank to seek legal advice from its external counsel were not protected by legal advice privilege as the employees in question did not form part of the “client” for privilege purposes. The Court held that it had to reach this conclusion by applying the narrow interpretation of “client” from the Court of Appeal in Three Rivers. In the ENRC Decision, the Court endorsed the decision in RBS and held that:

“If the client had been an individual, and the solicitor carried out evidence-gathering or fact-finding investigations by speaking to that individual’s current employees, his communications with those employees would not be subject to legal advice privilege simply because he was obtaining the information from them for the purpose of giving legal advice to their employer. It makes no difference whether the employees have been authorised to speak to him or not.”[14]

Who is a legal advisor for the purpose of legal advice privilege?

Not all qualified lawyers will constitute a ‘legal advisor’. In the ENRC Decision, in relation to the emails in category four, the Court rejected ENRC’s submission that they recorded “requests for and the giving of legal advice by a qualified lawyer acting in the role of a lawyer”. While the head of the mergers-and-acquisitions team was a qualified lawyer at the time, he was not engaged by ENRC as a lawyer, rather he worked in a mergers-and-acquisitions business role. The Court noted that even though the employee thought he was acting as a lawyer “because M&A work will often have a legal dimension to which he could bring the perspective of a qualified lawyer,” this was not sufficient for legal advice privilege to apply because it was not his duty to act in the role of legal advisor to ENRC.[15]

Interview notes prepared by legal advisors during the course of an investigation

Where notes are prepared during the course of interviews with employees or former employees undertaken on behalf of the corporate entity, legal advice privilege will not protect those notes from disclosure in most circumstances. This applies regardless of whether the notes are made by an employee of the corporate entity to provide to a lawyer, or whether the notes are made by, or in the presence of, a lawyer. This is because this kind of information is merely preparatory to enabling the corporate entity to seek and receive legal advice.[16]

In the ENRC Decision, the Court considered whether legal advice privilege protected the notes of interviews of individuals including former and current employees which had been prepared by its lawyers, Dechert, during the self-reported investigation. The Court held that the notes were not protected by legal advice privilege because there was no evidence that the interviewees were authorised to seek and obtain legal advice on behalf of ENRC, and the communications between the interviewees and Dechert were not communications conveying instruction to Dechert on behalf of the corporate client.[17] Applying Three Rivers, the Court held that, in any event, if ENRC had intended to take legal advice as a result of Dechert’s investigations and this was one of the purposes of making the interview notes, the notes were part of the preparatory work of compiling information for the purpose of enabling it to seek and receive legal advice, and therefore the notes were not privileged.

It may be possible in certain circumstances to claim that a lawyer’s notes of an interview are protected under legal advice privilege as “lawyers working papers”. To claim this sub-category of legal advice privilege, any notes would need to include an indication of the lawyer’s advice, or reveal the “trend of advice” being given (as opposed to being a verbatim transcript, or reflecting a “train of inquiry”), and this would need to be sufficiently demonstrated in order to resist disclosure.[18] In RBS, the interview notes were annotated with a comment that they reflected the “mental impressions” of legal counsel. The court held that this was not sufficient to engage legal advice privilege especially in the context that in the US this kind of notation was understood to be routine, aimed at invoking the limited protection conferred by the US Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26(b)(3).

In the context of internal investigations, some information which is already in the public domain may form part of the “continuum of communication” between a client and a lawyer, the purpose of which is the giving or receiving of legal advice. In the ENRC Decision, the Court gave the example of a situation where a copy of a report from a private investigator was sent by a client to its solicitor, seeking advice as to what to do in respect of the findings of the investigator. The copy of the report sent to the solicitor and any quotations of it in correspondence to or from the solicitor and the client in this situation would be privileged, even though the original report would not be privileged.[19]

Implications for global investigations

The English approach to legal professional privilege should also be borne in mind by companies operating in multiple jurisdictions that are carrying out investigations elsewhere. It is a well-established principle or convention of the English courts that privilege will be determined by way of the lex fori – i.e. the laws of the jurisdiction in which the claim has been brought.

This means that if a UK regulator is seeking to obtain disclosure of any interview notes, or disclosure is sought in any English proceedings, then English law would apply.[20] The fact that documents are privileged in another jurisdiction will typically not affect whether a document is considered privileged under English law. While the Courts retain a discretion to refuse to order disclosure, production or inspection of a document, and the fact a document is privileged in another jurisdiction may be relevant to a Court’s exercise of its discretion, this is likely to require a “special case”.[21] In RBS the Court declined to exercise its discretion.

The English approach also potentially raises questions in other jurisdictions, such as whether information that is held not to be privileged under English law, and as such is disclosed, could then be used against the company in a foreign jurisdiction where, but for the disclosure in accordance with English law on privilege, the information would be confidential in that foreign jurisdiction.

Concluding comments – navigating the currents

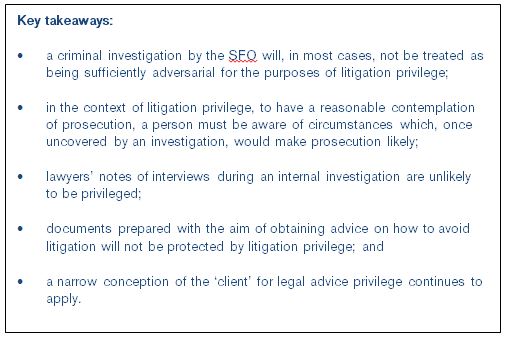

The ENRC Decision has continued the trend of English Courts applying a restrictive approach to the application of legal professional privilege, both in terms of litigation privilege, and legal advice privilege, where it applied the principles in Three Rivers (No. 5) and RBS. The Court has, however, provided new clarity on the issues of when, during a criminal investigation, adversarial litigation will be in reasonable contemplation, and what evidence a party must provide in order to satisfy the conditions required to successfully claim litigation privilege.

While the judgment is well-reasoned, the ramifications of both the ENRC Decision and RBS have attracted significant attention and comment within the legal profession, financial sector and broader business community, with some policy concerns being expressed. The decisions also emphasise the current divergence of approach to privilege between England and some other leading common-law countries.[22] We understand that permission has been sought from the Court of Appeal to appeal the ENRC Decision. As the Court itself acknowledged in the ENRC Decision, if there is to be any change of approach to legal professional privilege this will need to be made at the Supreme Court level, or by Parliament.

Unless and until the principles established by Three Rivers (No. 5), RBS and the ENRC Decision are revised by the Supreme Court, the current position is that the situations in which legal professional privilege can be claimed in relation to internal investigations are limited. If they have not already done so, companies should consider carefully their approach to corporate internal investigations and how, and to what extent, they engage in self-reporting processes in a criminal context.

[1] Three Rivers District Council and others v The Governor & Company of the Bank of England and another (no 5) [2003] EWCA Civ 474; [2003] QB 1556

[2] Re the RBS Rights Issue Litigation [2016] EWHC 3161 (Ch)

[3] ENRC was delisted in 2013 and is now wholly owned by Eurasian Resources Group

[4] See: 2(9) CJA 1987

[5] [2017] EWHC 1017 (QB)

[6] Three Rivers DC v Bank of England (No 6) [2004] UKHL 48, [2005] 1 AC 610 per Lord Carswell at [102]

[7] USA v Philip Morris [2003] EWHC 3028 (Comm) at [46]

[8] ENRC Decision at [154]

[9] ENRC Decision at [155]

[10] [2012] CAT 6

[11] ENRC Decision at [61]

[12] ENRC Decision at [166]

[13] See further discussion below

[14] ENRC Decision at [87]

[15] ENRC Decision at [190]

[16] RBS applying Three Rivers (No 5)

[17] ENRC Decision at [177]

[18] See RBS at [107], [121] – [126], and the ENRC Decision at [97] and [178]

[19] See the ENRC Decision at [182]

[20] RBS at [169]

[21] RBS at [182] – [185]

[22] Such as the US, Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore

/>i

/>i