The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began 2025 with a resolution to make food “healthy” again by announcing a trio of new final and proposed rules that are intended to make it easier for consumers to identify healthy food choices. These rules – which include a new ban on the use of red dye No. 3, a revised definition of what “healthy” claims can be made about foods, and new proposed requirements for nutritional labeling on the front of food packaging – have implications for many stakeholders in the food industry.

Although these healthy food initiatives were initiated under the Biden Administration, they directly align with the new Trump Administration’s agenda for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The recently confirmed Secretary of HHS under the second Trump administration, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has campaigned on limiting the use of food dyes and taking aim at highly processed “junk foods” that contribute to obesity. Therefore, we expect that these new rules will be here to stay, despite the new administration’s recent freeze on new proposed rules and recommended postponement of new final rules (which is currently pending court review). Regulated stakeholders should take steps now to prepare for compliance.

Revocation of Use of Red Dye No. 3 in Food and Ingestible Drugs

On January 16, 2025, FDA announced that it amended its color additive regulations to revoke the authorization for the use of FD&C Red No. 3 (commonly known as “red dye No. 3”) as a color additive in food and drugs (90 Fed. Reg. 4628 (Jan. 16, 2025)). Therefore, effective January 15, 2027, red dye No. 3 will no longer be permitted for use in food products, such as candy, cakes, cupcakes, cookies, frozen desserts, frostings, and icings, and all certificates for the use of red dye No. 3 in such products will cease to be effective. Red dye No. 3 will be banned from use as a color additive in ingestible drugs, effective January 18, 2027. Any food and ingestible drug products (including imports) containing red dye No. 3 without effective certification will be considered adulterated.

Notably, although other countries still permit certain uses of red dye No. 3 (sometimes called “erythrosine” abroad), foreign manufactured food products imported into the U.S. will also need to comply with this new ban. Though FDA has not yet signaled whether the implementation of this new rule will be delayed further, food industry members should take steps now to reformulate any products containing red dye No. 3.

FDA’s action on red dye No. 3 is not surprising to some extent, considering that the agency revoked use of the dye in cosmetics in 1990, and its use is already prohibited in food in other countries. What remains to be seen is whether FDA will continue down the regulatory path it has begun. Petitions are presently before the agency to ban other chemicals in food use, such as PFAS, BPA, TCE, and titanium dioxide—some of which have been pending for years. Further, prior to the change in administrations, FDA announced that it is developing a “systemic process” for conducting post-market assessments of chemicals in food, including GRAS ingredients, color additives, food contact substances, and potential contaminants, and established a docket for public comment. By the time the comment period closed, more than 34,000 comments had been submitted to FDA, signaling significant interest in this issue. Given the new HHS Secretary’s stated priorities, it would not surprise us if FDA continues its rulemaking efforts in this space.

Updated Requirements for “Healthy” Claims

In recent years, FDA has expressed concern over the growing prevalence of preventable chronic diseases and health conditions associated with unhealthy diet choices. Because FDA’s research demonstrates that U.S. consumers choose foods based on information readily (and easily) available to them, FDA has focused its attention on revising its food labeling regulations to provide consumers with additional information about a food’s nutritional benefits (or lack thereof). The result is the revised final rule for “healthy” claims and a proposed rule mandating front-of-pack nutrition disclosures, as discussed below.

The preambles to these rulemaking efforts demonstrate that FDA’s thinking has been heavily influenced by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (the “Dietary Guidelines”). Under the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and HHS must publish the Dietary Guidelines at least once every five years, based on the current state of scientific and medical knowledge. The current Dietary Guidelines deemphasize the importance of individual nutrients or food groups in isolation in favor of a more holistic approach that focuses on dietary patterns during different life stages. A healthy dietary pattern, according to the Dietary Guidelines, emphasizes nutrient dense foods across all food groups, while staying within calorie limits and limiting sugars, saturated fats, and sodium.

FDA regulations have included parameters on “healthy” claims since 1994, but the requirements have not significantly changed since that time, even though nutrition science has evolved. The parameters established under the original rule were fairly rigid, and included specific limits on total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and sodium, as well as minimum amounts of nutrients whose consumption was encouraged (e.g., vitamin A, iron, protein). Under the 1994 rule, a food had to meet all the limits of the “discouraged” nutrients and contain the minimum amount of at least one of the “encouraged” nutrients to bear a “healthy” claim. That had the effect of excluding certain “nutrient dense” foods often viewed by consumers as healthy, such as salmon (due to its fat content).

The new Final Rule (89 Fed. Reg. 106,064 (Dec. 27, 2024)) proposes a more flexible approach consistent with the revised Dietary Guidelines. Current nutrition science emphasizes nutrient-dense foods – such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains – as part of a healthy dietary pattern. Nutrient-dense foods and beverages are defined as those that provide vitamins, minerals, and other health promoting nutrients but also have little or no added sugars, saturated fats, or sodium. Accordingly, foods that meet the requirements for “healthy”, as defined in the new rule, are foods that, because of their overall nutrition profiles, can be the “foundation” or “building blocks” of an overall healthy dietary pattern recommended by the Dietary Guidelines.

Under the rule, a “healthy” food claim “[s]uggests that a food, because of its nutrient content, may be useful in maintaining healthy dietary practices, where there is also implied or explicit information about the nutrition content of the food (e.g., “healthy”).” See 89 Fed. Reg. 106,064, 106161. In general, to meet the new parameters for “healthy” food claims, including claims that foods are “healthful” or “healthier”, food products (including individual foods, mixed products, main dishes, and meals) must (1) for example, contain a certain amount of food (referred to as a “food group equivalent”) from at least one of the food groups or subgroups recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (e.g., vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fat-free or low-fat dairy, lean meat, seafood, eggs, beans, peas, lentils, nuts, or seeds) and (2) meet specific limits for added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium (based on a percentage of the Daily Value (DV) for these nutrients). Under the new criteria, some categories of foods – vegetables, fruits, seafood, lentils, nuts and seeds, among others – automatically qualify for the “healthy” claim due to their nutrient density, so long as they do not contain any additional ingredients other than water. And some foods that did not qualify for a “healthy” claim under the old rule due to their fat content now do, including avocados, salmon, and olive oil. Conversely, some food products that qualified as “healthy” under the old rule now do not, including fortified white bread, highly sweetened yogurts, and highly sweetened cereal.

The new rule also contains a substantiation requirement. Manufacturers of foods for which “healthy” claims are made must make and keep written records substantiating the “healthy” claims in accordance with the new requirements, except where nutritional food labeling makes clear that the requirements are met.

The food industry may begin voluntarily complying with the new rule on or after February 25, 2025, and must comply by February 25, 2028. Therefore, the food industry should take steps now to review any “healthy” claims made for their products, assess whether those claims should be changed in light of the new final rule, and document the substantiation for their claims.

We add that health claims on food labeling are heavily policed by consumer class action attorneys under consumer fraud laws (particularly in California and New York), and that compliance with FDA’s requirements for “healthy” claims will not necessarily preempt these lawsuits, if a court determines that other aspects of the label or packaging renders the claim misleading on the whole. Therefore, food manufacturers should work closely with experienced counsel in formulating “healthy” claims and ensuring that these claims are properly substantiated.

Nutrition Labeling

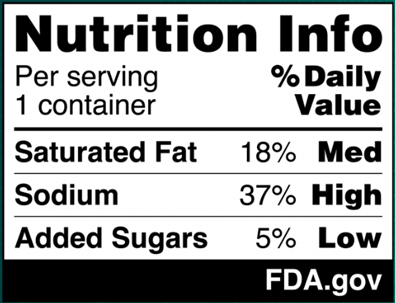

On January 16, 2025, FDA published a proposed rule (90 Fed. Reg. 5426 (Jan. 16, 2025)) (the “Proposed Rule”), which, if finalized, would require a front-of-package nutrition label called a “Nutrition Info box” on most packaged foods to assist consumers in more easily identifying healthy foods. This new label would require manufacturers to address the relative amounts of saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars in a serving of the food, and identify whether those amounts are low, medium, or high. FDA’s proposed format for the new label appears below:

The ranges that FDA proposes for each category are as follows:

- Low: 5% daily value (DV) or less

- Medium: 6% to 19% DV

- High: 20% DV or more

In proposing these DV ranges, FDA considered the regulatory history of the percent DV; the agency’s commitment to helping consumers understand the percent DV concept in the context of a person’s daily diet; and the agency’s existing regulatory definitions for nutrient content claims (including definitions established for “low” and “high” claims), among other factors. FDA believes that the ranges it proposes for the interpretive descriptions – and in particular, its designation of 5% DV or less as “low” and 20% DV or more as “high” – align with its longstanding regulatory approach.[1] However, FDA invites comment on its conclusions and analysis.

Calorie disclosures

In the Preamble to the Proposed Rule, FDA acknowledged that some manufacturers already voluntarily include a calorie statement on the front of the food packaging, in accordance with existing regulations. FDA invites comment from industry stakeholders on the inclusion of a mandatory or voluntary statement of calories in the proposed Nutrition Info box, as well as suggestions as to how FDA could consider including quantitative calorie information (e.g., “low”, “medium”, “high”) in the box (including any new data or other information on which FDA could base this interpretation).

Anticipated costs

One notable aspect of the Proposed Rule is its anticipated cost to industry, which FDA analyzed as part of the rulemaking effort. FDA quantified the estimated costs of relabeling to the packaged food industry as a whole to range between $66 million and $154 million per year over a ten-year time horizon. Further, although product reformulation is not a requirement or a stated goal of the Proposed Rule, FDA recognizes that the rule may result in voluntary reformulation efforts by some food producers. FDA estimates that the annualized costs of reformulation would range from $125 million to $377 million over a ten-year time horizon. FDA recognizes the possibility that some of these relabeling/reformulation costs may be passed along to consumers (at least in part).

If finalized, businesses with $10 million or more in annual food sales will be expected to comply with these requirements within three years of the final rule’s effective date. Businesses with less than $10 million in annual food sales will be expected to comply with the requirements within four years of the final rule’s effective date. FDA is accepting comments on this new proposed rule by May 16, 2025. Food industry stakeholders should consider submitting comments to this proposed rule. Foley’s Food and Beverage Industry Team members have extensive experience assisting regulated stakeholders in preparing comments on FDA rulemaking. Any of the authors would be happy to provide additional information.

Regulatory Freeze

As is standard practice for an incoming administration, one of President Trump’s first Executive Orders (“EO”) places a freeze on all pending regulations proposed in the last days of the Biden administration. The EO encourages a 60-day review of any such proposed rules or guidance, with further consultation by the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) as-needed for “for those rules that raise substantial questions of fact, law, or policy.”

Next Steps

Though there is some uncertainty about timing, overall, industry should plan for the possibility that these rules and orders will take effect. Therefore, food industry stakeholders should act now to:

- Begin planning on reformulation of products with red dye No. 3;

- Review and assess what “healthy” food claims are made about their products, and document their support for those claims in accordance with the new “healthy” framework; and

Consider submitting comments to the new proposed rule requiring front-of-package nutrition information labeling.

[1] FDA does not have a regulation that establishes a “medium” nutrient content claim for any nutrient. In the Preamble to the Proposed Rule, FDA effectively takes a common-sense approach to defining that term. See 90 Fed. Reg. 5426, 5445 (“The adjective ‘medium’ is defined as, for example, ‘being in the middle between an upper and lower amount, size, degree, or value . . . and ‘intermediate in quantity, quality, position, size, or degree’ . . . . The common meaning of the adjective ‘medium’, then, aligns with the meaning of the interpretive . . . we are proposing.”). Which is just to say that the “low” and “high” goalposts are really what matter for purposes of comment on the Proposed Rule.

/>i

/>i