WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW IN A MINUTE OR LESS

PFAS litigation is on the rise, but questions mount as to the science and motivation behind these cases.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) gained substantial marketplace acceptance for their ability to make products resistant to heat, oil, stains, grease, and water. More recently, PFAS products have attracted the attention of the plaintiffs’ bar—including those specializing in consumer litigation.

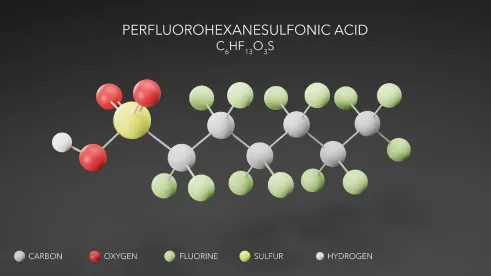

PFAS are found in innumerable consumer products, including food packaging and textiles. Over time, data developments have suggested that the unique chemistry responsible for PFAS’ incredible utility is also responsible for allowing PFAS to persist, rather than degrade, in the environment—leading these substances to be dubbed “forever chemicals.” As a result, the broad classification of PFAS has become an increasingly favorable target for litigation brought by the plaintiffs’ bar, despite the category encompassing a wide variety of chemicals with differing chemical and performance profiles.

With this recent surge targeting a variety of defendants under a variety of theories, the question arises whether alleged concern from claimed exposure to PFAS (i.e., in the absence of manifested injury) is an adequate basis to bring, and maintain, a class action lawsuit under most states’ consumer protection statutes.

Common Pitfalls: Consumer Class Actions

Although some cases in the consumer product category allege actual manifested bodily injury, most merely allege the purchase of a product positive for PFAS—and that the consumer would not have purchased the product if made aware of the PFAS content. This speculative argument is controversial for a few reasons. Lacking the overtly identified “deception” called upon in most false advertising cases, these targeted products often do not claim to be free of PFAS. Rather than employing deceptive claims, plaintiffs are relying on the presumption that a product is safe and suitable, suggesting that any presence of PFAS causes the product to be unsafe and unsuitable—alleging in some instances that general claims like “sustainable,” “organic,” or “natural” are misleading in light of detected PFAS. Some courts have called this practice into question, recognizing that the potential presence of an unintentional contaminant in a product does not preclude a company from making unrelated, positive claims about the product on the label.1

Plaintiffs also frequently pursue litigation without conducting their own testing. Rather, they rely on invalidated third-party testing, with lawsuits most commonly hinging on studies conducted or published by watchdog organizations or media outlets (e.g., Consumer Reports, Toxin Free USA, or investigative bloggers such as Mamavation). For example, after conducting her own testing on self-tanning products, makeup, feminine hygiene products, dental floss, and more, the blogger behind Mamavation shares the test results on her website, identifying products containing PFAS and companies to avoid. These results are becoming a common off-the-shelf source for plaintiffs’ attorneys in plug-and-play class-action claims—and for media use in unflattering articles.

Additionally, when conducting testing, plaintiffs often rely upon more generalized testing for total organic fluorine, rather than testing specifically for PFAS. Regardless of any alleged risk from PFAS, organic fluorine is not harmful, and such testing may provide positive test results for organic fluorine in the absence of PFAS. Plaintiffs’ failure to test for all PFAS, including those alleged to be harmful, can be fatal to their claims.

Court Considerations

Courts have called into question these practices as well. For example, some medical devices contain polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), a type of PFAS approved by the FDA. In this context, a District of Columbia (D.C.) court recently held that “different PFAS have [sic] different health effects” and that “PTFE has not been found to be toxic or environmentally unsafe.”

Another D.C. court dismissed putative claims against a maker of dental floss, finding that the study cited by plaintiffs did not support their claims as it only “hypothesized that the dental floss might be a potential exposure source for PFAS.” The floss actually tested was never tested for PFAS, but for fluorine, “which indicates that +PFAS might be present.”2

Defendants often challenge the dubious approaches described above by challenging Article III standing at the motion to dismiss phase under Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 12(b)(1). Specifically, defendants argue that plaintiffs do not have standing to pursue the challenge without adequately pleading an injury in fact. So far, the results of these challenges are mixed, with several courts around the country finding defendants’ arguments persuasive, while others allow cases to proceed with minimum pleading effort and claim foundation.

Takeaway

While PFAS have undoubtedly advanced many industries, these industries can no longer ignore the attendant regulatory and litigation risks presented in the face of an increasingly aggressive plaintiffs’ bar. PFAS-based challenges are likely here to stay for the near term, and laboratories are making efforts to develop enhanced PFAS testing capabilities that could aid the arguments of both the plaintiff and defense bars.

With the current increase in this trend, companies—even those not intentionally using PFAS—should consider the potential risk of PFAS litigation. Consulting with experts (including product labeling and regulatory lawyers, as well as class-action litigation and insurance coverage specialists) and monitoring litigation and regulatory developments are critical parts of managing that risk.

/>i

/>i