As expected, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) voted 3-2 yesterday to issue its final noncompete rule, with only a few changes from the proposed rule that are discussed below. Unless it is enjoined, which we expect, the rule will become effective 120 days after publication of the final version in the Federal Register.

If the final rule survives the legal challenges, which are likely to make it all the way to the United States Supreme Court, all new non-competes would be banned. Except for existing non-competes for senior executives (as defined below), all existing noncompetes with employees would also be banned. A senior executive is defined as “a worker who was in a policy-making position” and who received total annual compensation of more than $151,164. Garden leave agreements, pursuant to which an individual remains an employee and is paid their regular compensation during a mandatory notice period, would be permissible, as well as confidentiality and non-solicitation agreements, provided that they do not prohibit, penalize, or function to prevent a worker from switching jobs or starting a new business. In contrast, paid noncompete periods (sometimes also called garden leave provisions, but different than paid notice periods) would be prohibited.

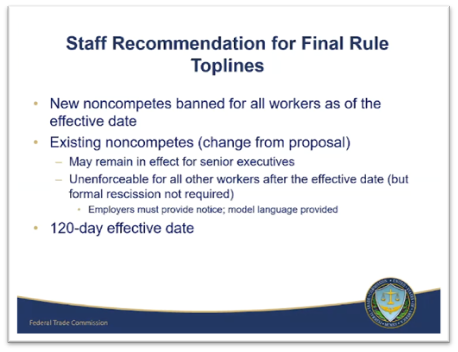

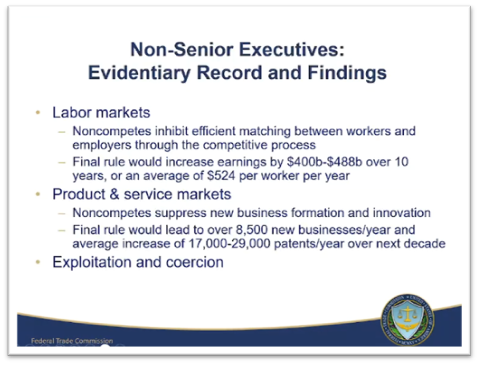

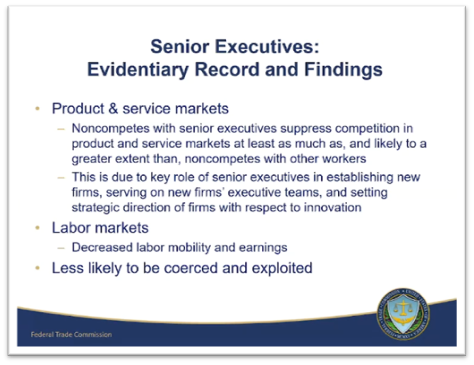

Prior to the vote, an FTC staffer presented on the rule. Although claiming to have read each and every one of the more than 26,000 comments submitted in response to the proposed rule, the staffer only referenced and quoted from a few proponents of the rule (i.e., some employees and small business owners). He did not quote any opponents of the rule. He then presented the following slides that explained the FTC’s reasoning behind the rule, doubling down on the flawed research findings we have discussed previously, and summarily dismissing any concerns about the rule raised by its opponents:

The Commissioners each then had a chance to speak. As expected, Chair Khan and Commissioners Slaughter and Bedoya supported the rule and, indeed, suggested it does not go far enough because it does not cover franchisees in the context of a franchisee-franchisor relationship or workers at properly classified nonprofits. Commissioners Holyoke and Ferguson pointed out what we have long said: the FTC does not have the Congressional authority to promulgate the rule. Commissioner Ferguson stated that the FTC lacks “the power to nullify tens of millions of existing contracts,” and stated his intention to write a dissenting opinion. Chair Khan summarily dismissed this argument.

As a reminder, the Rule would ban post-employment noncompetes nationwide. The only changes the FTC made to the proposed rule are that:

- responding to what was perhaps the business community’s biggest stated concern, and bringing the rule in line with California, the FTC removed the 25% equity threshold for noncompetes entered into in connection with the bona fide sale of a business (i.e, noncompetes are permissible in the context of the sale of a business irrespective of the sellers’ ownership interest, provided it is a bona fide sale and not a sham transaction);

- noncompetes entered into with “senior executives” prior to the effective date of the rule will remain enforceable, but not agreements with senior executives entered into thereafter;

- the rule includes a “functional” test for what constitutes a noncompete, removing reference from the proposed rule to “de facto” noncompetes, although they are effectively one and the same (although no less ambiguous as now written in our view);

- there is an exception for causes of action accruing prior to the effective date of the rule;

- while employers no longer need to affirmatively “rescind” existing noncompete agreements, the FTC provided updated guidance and form language on how to provide notice to individuals that their noncompete will not be enforceable or enforced (again, effectively the same as requiring rescission, but just using different verbiage); and

- the effective and compliance date is now 120 days after publication of the final rule in the Federal Register (previously the effective date was 60 days and the compliance deadline 180 days later).

As noted above, while the senior executive exemption is of limited import because it only applies to preexisting noncompetes with a narrow category of workers, and the pending litigation exception is likewise very limited given that all pending litigation will eventually come to an end, the sale of a business change is actually quite important because it brings the final rule in line with California and allows noncompetes to be entered into with sellers of a business provided the sale is bona fide (or, as they say in California, not a “sham” transaction).

Similarly, the functional test for what constitutes a noncompete could be a big change as it may be interpreted to cover other types of restrictive covenants such as non-solicit provisions in certain circumstances. The functional test leaves uncertainty with respect to non-solicit provisions in that the final rule “does not categorically prohibit other types of restrictive employment agreements, for example, NDAs, TRAPs, and non-solicitation agreements.” Yet, the FTC later states that if an employer adopts a non-solicit “that is so broad or onerous that it has the same functional effect as a term or condition prohibiting or penalizing a worker from seeking or accepting other work … such a term is a non-compete clause under the final rule.” Should the rule not be enjoined, as expected, employers should pay attention to the effective/compliance date.

The FTC recognizes it lacks jurisdiction over corporations “not organized to carry on business for its own profit or that of its members.” However, after an extensive discussion of the health care industry and, among others, nonprofit hospital systems, the Commission warned, “not all entities claiming tax-exempt status as nonprofits fall outside the Commission’s jurisdiction.” The FTC noted that it “looks to the source of the income, i.e., to whether the corporation is organized for and actually engaged in business for only charitable purposes, and to the destination of the income, i.e., to whether either the corporation or its members derive a profit.” Unless an organization passes this “two-prong test,” the Commission insists they are bound by the final rule regardless of their claimed tax exemption.

* * *

We do not believe the rule will ever go into effect. At the very least, it is likely to take years for the rule to work its way through the courts following pending and inevitable legal challenges. Thus, there is no reason for panic or, really, any changes to current policies and practices. That said, given that the issue is front of mind for many executives and boards, and the fast pace of change in state legislatures across the country, we recommend that employers consider taking a holistic review of their restrictive covenant and trade secret strategy to determine whether the strategy is effective, whether it can and should be tweaked in light of recent and anticipated developments, and what other options should be considered for protecting the company’s most important intangible assets, including strengthening and increasing the use of non-solicitation and confidentiality clauses, using advance notice of resignation or termination clauses (i.e., traditional garden leave clauses), using employment agreements of a fixed duration, and focusing on increased trade secret protection through a trade secret audit.

/>i

/>i