Although the mineral deposits in the high seas are designated under international law as the “common heritage of mankind,” the deep-sea mining (DSM) industry has already turned into a goldrush, where a select number of governments and companies in the Global North exert de facto control. Some of these industry giants have been sanctioned in the past for corruption or environmental destruction and it is highly possible that many of them engage in corrupt and fraudulent activities in order to obtain and maintain their contracts.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which awards deep-sea exploration and exploitation contracts, and which is shrouded in secrecy itself, currently lacks adequate whistleblowing and regulatory frameworks to effectually carry out its mandate of protecting the seabed, regulating the industry, and ensuring that all DSM activities are “for the benefit of humankind as a whole.”

It is impossible to combat corruption in DSM and regulate the industry without whistleblowers. States must demand that ISA implement a whistleblower program that follows best practices, complemented by enhanced anti-corruption and environmental protection regulations. It’s also critical for the international community to raise awareness about existing transnational whistleblower laws, which can be used by whistleblowers worldwide to report violations by many of the companies who currently hold exploration contracts.

ISA’s Problems with Bias and Transparency

The obvious challenge with determining whether Deep Sea Mining activities are “for the benefit of humankind as a whole” is that it is a completely arbitrary standard. It is often interpreted as a question of whether DSM will have a “net” benefit, but of course, there is no consistent way to evaluate net human benefit.

Given the existing ambiguity in the standards, it is especially important for ISA to be transparent and as leased biased as possible about determining who is awarded exploration contracts, what the results of the studies are, and what factors will be used to determine whether an exploitation contract will be granted.

However, the reality is that ISA lacks basic guardrails against conflict of interest and operates in a high level of secrecy.

An LA Times article explained that major conflict of interest concerns arose after one of the leaders in the DSM industry, the Metals Company (DeepGreen Metals at the time) released a promotional video featuring Michael Lodge, the Secretary-General of ISA, where Lodge seems to depart from a neutral stance. The article quotes Sandor Mulsow, who formally served as ISA’s top environmental official for over five years: “The ISA is not fit to regulate any activity in international waters… It is like to ask the wolf to take care of the sheep.”

Members of civil society find it challenging to hold ISA accountable due to extreme lack of transparency within the authority. Even the 36 nations that serve on ISA’s Council have critiqued that they are prohibited from knowing basic information necessary to do their jobs, such as the names of companies involved in contract negotiations (the Secretary-General negotiates mining contracts personally with companies). ISA also does not publish the identities of companies who fail to comply with environmental reporting standards, let alone publish the results of the environmental impact analyses – including to states on the Council, resulting in no repercussions for companies who fail to comply with these standards.

The conflict of interest and lack of transparency within ISA can (and likely already has) led to the prioritization of profit maximization over the prioritization of environmental protection, only the latter of which is ISA’s duty. It is not possible for ISA’s leadership to fairly assess whether DSM will benefit humankind if they stand to benefit personally from mining contracts, and it is not possible to reach a consensus about whether DSM would provide a “net” benefit unless all states are given the necessary information.

ISA’s Regulatory Failures

ISA has also failed to establish the regulatory framework necessary to prevent the DSM industry from benefiting the Global North at the expense of the Global South. The UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS) creates several profit-sharing mechanisms. It siphons off some of the mining area – called the “Reserved Area” to be reserved exclusively for developing states. UNCLOS requires that developing nations working with ISA receive access to data in certain mining areas before companies. The Convention also includes a loss and damages mechanism for compensating countries who are harmed by DSM.

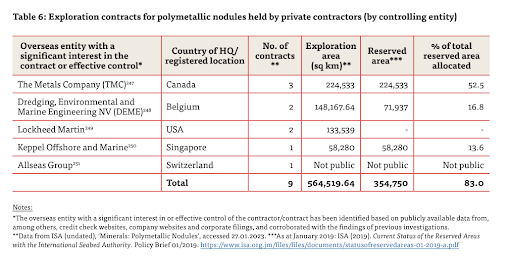

However, in practice, companies based largely in the Global North – some of which have strong ties to ISA and some of which have a record of nefarious activity – currently have effective control of at least 83% of the total Reserved Area allocated, according to The Environmental Justice Foundation’s report “Towards the Abyss” (see graph from EJF below). Under UNCLOS, any contract awarded to a company must be sponsored by a state, and that state must have “effective control,” but ISA regulations do not define effective control and therefore do not require companies who are awarded contracts to be economically controlled by the sponsor state or even a national of the sponsor state.

Despite this, ISA still holds states liable for all risks and damages associated with mining, including potentially vast environmental damage. This means that companies based in the global north, or their subsidiaries, can contract with developing nations, maintain most of the profit, and still would not be primarily responsible for damages that could result from their risky activities.

Exploration contracts for polymetallic nodules held by private contractors (by controlling entity); source: EJF

The Metals Company, a Canadian mining corporation which effectively controls over half of the Reserved Area, has faced criticism for its history of recklessness towards the environment and towards developing sponsor countries, as well as for the means through which it obtained its current contracts in the Reserved Area. The company’s CEO, Gerard Barron, formerly helped to lead Nautilus, which was the first company ever granted a license for deep sea mining in 2011, sponsored by Papua New Guinea. Ultimately, the project collapsed because Nautilus was unable to pay its debts. Papua New Guinea lost $120 million, which is almost a third of its annual health budget, and there are ongoing effects on ancient cultural fishing practices.

Despite his involvement in this crisis, Barron is now the CEO of The Metals Company, which has exploration contracts sponsored by the Pacific Island nations of Nauru, Tonga and Kiribati. According to a New York Times investigation, the ISA provided data that should have been provided directly to a developing country first, to an executive at the Metals Company, allowing them to subsequently secure Nauru and Tonga as sponsors, rather than the countries seeking out a company with whom to contract. The sponsorship agreement provides minimal benefit to these developing Pacific Island nations. The Metals Company maintains rights to almost all of the profits, except for a small percentage paid to the sponsors.

The lack of regulations designed to enforce the equitable exploration of and profit sharing from DSM not only violates the intent of UNCLOS, but likely relies on corrupt activity that is already illegal and sanctionable for many UN member states.

A Whistleblowing Mechanisms for ISA

Whistleblowers are essential to enhancing transparency and combatting corruption within ISA and the Deep Sea Mining industry. The ISA’s draft regulations on exploitation, which were introduced during its twenty-ninth session in March 2024 (in part as a response to criticisms about lack of transparency and regulatory structure), include a draft whistleblower policy. It states that either the Compliance Committee or the Assembly, in collaboration with the Council, “shall develop and implement: (a) whistleblowing policy for the staff of the Authority, the Enterprise, and personal of Contractors, and (b) a public complaints procedure to facilitate reporting to the Authority by any person of any concerns about the activities of a Contractor or the Authority.”

It continues that “(2) The whistleblowing and complaints procedures under this Regulation must: (a) be publicly advertised, (b) be easy to access and navigate, (c) enable anonymous reporting, (d) trigger investigations of reports by independent persons, and (e) be proactively communicated by the Secretary-General to Contractors and their staff, and other Stakeholders.”

Finally, the draft regulation would require contractors, their subcontractors, and their agents to have whistleblowing complaint procedures in place, which must be publicly advertised and which include details of the Authority’s procedures.

The inclusion of a whistleblower program in the draft regulations is certainly a good start. It incorporates important provisions such as anonymity rights and requirements to publicly advertise whistleblower programs. However, three additional components must be considered in order to have a truly effective whistleblower program within ISA, rather than one that simply checks the boxes.

First, whistleblowers who report internally are at much higher risk of retaliation – even if they are technically protected by the right to report anonymously (see for instance: Whistleblower Disclosures: An Empirical Risk Assessment, which found that 95% of whistleblower retaliation under two white collar crime laws was faced by whistleblowers who reported internally to their employers rather than to the government). It is dangerous to house a program where people could blow the whistle on ISA within ISA. The very structure would deter whistleblowers with critical information from reporting due to fear of retaliation or lack of trust. It would be safer to establish an independent office of the whistleblower for ISA housed under a distinct UN agency with a good reputation for transparency and protection of vulnerable groups, such as OHCHR. The “independent groups” who would be responsible for conducting investigations under the draft whistleblower policy should be identified in the final policy, and the appropriate UN agency could make referrals to them. If the final regulations changed this and imposed a punishment for violating whistleblowers’ anonymity rights (there is no punishment under the current draft), it could create a real protection of whistleblower anonymity.

Second, ISA should provide whistleblowers with a percentage of any financial sanctions brought about through their whistleblowing. Blowing the whistle is an enormous risk, even if the right to anonymity technically exists. Offering whistleblower rewards is essential to overcoming this risk (see: Why Whistleblowing Works: A New Look at the Economic Theory of Crime). By giving financial value to their information, whistleblowers are incentivized to come forward.

Third, an effective whistleblower program must lead to enforcement. Whistleblowers will only take on the enormous risk of trying to stop powerful companies if there is an assurance that they will not be potentially sacrificing their livelihoods in vain. Therefore, ISA’s whistleblower office must be equipped with excellent investigators whose investigations can result in potential sanctions, disgorgement of profit, debarment, and significant fines and penalties, among other punishments.

These three components – anonymity, compensation, and enforcement – are fundamental to maximizing the anti-corruption potential of whistleblowers. Whistleblowing is a highly risky business; without these measures in place, blowing the whistle is often the irrational thing to do. Therefore, mobilizing whistleblowers requires changing the risk calculus and making the conditions right for them to report.

Recommendations for New Regulatory Framework in ISA:

Ultimately, whistleblowers can only be useful when there is a strong regulatory framework in place to prevent risky/nefarious activity. ISA needs to increase transparency and strengthen its regulatory framework to fulfill its mandate. Once it does so, whistleblowers will have clear regulatory violations to report and it will become easier to identify and disqualify or punish people and companies that pose a threat to “the common heritage of mankind” – either due to environmental violations, unfair competition, deceitful beneficial ownership, or some combination of the above.

ISA should implement the following recommendations:

- Ensure that the company has a solid environmental record and proof of strong whistleblower protections. For instance, companies like TransOcean, which was responsible in part for the 2010 Gulf Oil Spill but is nonetheless competing for DSM contracts, should not be eligible for such contracts given its record, nor should any company with leaders involved in other environmental catastrophes or fraud schemes.

- The companies must consistently meet environmental reporting measures, which are to be publicly available – both within the Council and to civil society on the ISA website.

- The companies must meet and comply with whistleblowing standards, which they are to make public, and which should include an anonymous internal claims mechanism as well as education about external reporting rights.

- There needs to be a debarment mechanism, which excludes parties who have a history of reckless environmental impact and/or retaliation against whistleblowers from being awarded contracts.

- Institute guardrails against conflict of interest, bribery, and bias within the authority in order to guarantee that mineral companies do not exert undue influence over the authority’s decisions. Such guardrails should include:

- Requiring the Secretary-General and members of the Commission to pass a conflicts of interest screen, confirming they do not have any financial ties or stake in or against DSM companies.

- Prohibiting the Secretary-General and other leaders in the ISA from participating in marketing for DSM companies and maintaining a position of neutrality.

- Automatically exclude or fire any personnel who are found to have engaged in bribery (any money, good, or service in exchange for political or business advantage) from ISA.

- Create regulations to ensure that contracts issued in the reserved area are actually benefiting developing countries, including by:

- Defining “effective control” of sponsor states to mean that a sponsor state receives at least 25% of the profits.

- Requiring that at least another 25% of the profits be put into the loss and damage fund to compensate countries harmed by DSM.

- ISA should require that the ultimate beneficial owner in each contract issued is the sponsor state or people within the sponsor state.

If ISA implements these recommendations, it would increase the realm of whistleblower claims that could lead to enforceable action.

The Applicability of Transnational Whistleblowing Laws:

In the meantime, while ISA still lacks an adequate regulatory framework to enforce international law and lacks a whistleblower program altogether, whistleblowers in the DSM industry can utilize effective transnational U.S. whistleblower laws to hold companies accountable for fraud and corruption. It is critical that international organizations and civil society leaders help to educate potential DSM whistleblowers about these laws so that witnesses to fraud and corruption in the industry understand they have a very effective option for reporting and enforcement.

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) is a U.S. law that prohibits the payment of bribes (anything of value) to foreign officials for a business advantage. The FCPA covers almost any publicly traded company (i.e. not just companies headquartered in the United States, but any company that permits U.S. investors to invest in it).

This may be applicable to Deep Sea mining in two ways. First, whistleblowers can identify bribery between DSM companies and the states sponsoring them. Second, whistleblowers can identify bribery within the ISA itself. The United States Department of Justice FCPA Guide states that “In 1998, the FCPA was amended to expand the definition of ‘foreign official’ to include employees and representatives of public international organizations.”

Dodd-Frank Act: SEC and CFTC

In 2010, the United States passed the Dodd-Frank Act, which created sister whistleblower programs under the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) and U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) for securities fraud and commodities fraud, respectively. SEC and CFTC whistleblowers can report anonymously and receive rewards between 10 and 30% of the ultimate monetary sanction.

FCPA whistleblowers who report to either the SEC or CFTC also qualify for rewards under Dodd-Frank. Additionally, whistleblowers may be compensated for “related actions,” i.e. recoveries by agencies other than the SEC or CFTC. The related action provision of Dodd-Frank allows whistleblowers to collect for reporting environmental violations.

If a company makes materially fraudulent claims to investors (including failing to report environmental risks), there could be a case under the SEC’s Dodd-Frank program. If a company were to trade minerals mined in the deep sea through any illicit means – whether that means before obtaining proper approval or through bribery or fraudulent means – then there could be a case under the CFTC’s Dodd-Frank program.

Like the FCPA, any company in which a U.S. investor can invest could be sanctioned under the Dodd-Frank Act, meaning that nearly all of the private corporate entities and even some of the state-controlled corporations that have contracts for DSM are covered.

False Claims Act and the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships

Under the United States’ False Claims Act, any person that knowingly submits or causes to submit false claims to the U.S. government or who makes a material omission of the facts is liable for three times the government’s damages, plus a penalty. Under the qui tam provision of the FCA, whistleblowers can receive up to 30% of the proceeds collected by the government. A false claim related to Deep Sea Mining could include the submission of fraudulent environmental impact analyses or studies that omit key data by a company contracted through the U.S. government. The FCA is one of the most effective ways that big pharmaceutical companies are deterred from submitting fraudulent scientific research. It should be deployed to an even higher extent with scientific research in Deep Sea Mining, which may yield irreversible consequences.

The False Claims Act is also the legal basis for the United States’ Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS), which enforces the MARPOL Convention, an international law that restricts pollution on the high seas and institutes reporting obligations for certain activities. Under APPS, all U.S.-flagged ships are required to comply with MARPOL, and ships of any flags are required to report any pollution when they dock at a U.S. port. Fraudulent statements on these claims violate the False Claims Act, and under APPS, whistleblowers who report such violations may be rewarded up to 50% of the recoveries. Vessels engaging in Deep Sea Mining Exploration have certain unique obligations under MARIPOL and other obligations related to the discharge of harmful substances that are consistent with all ships on the high seas.

Conclusion

Corruption and fraud are notoriously hard to detect without whistleblowers because they happen behind closed doors. The essentiality of whistleblowers is only stronger in the deep-sea where the crimes are quite literally happening in the dark. Since the cost barrier is so high to conduct (and therefore to independently verify) research and since ISA only permits one contract to explore a certain geographical area at a time anyways, it is virtually impossible to detect when a DSM company is omitting important information or submitting fraudulent environmental data.

The stakes of not empowering whistleblowers – our best chance at undermining corruption in the DSM industry and within ISA – could not be higher. The International Union for Conservation of Nature states that the disturbance to the seafloor and resulting species extinction will most likely be permanent. Exploitative contract arrangements effectively controlled by companies in the Global North will perpetuate legacies of economic colonialism that UNCLOS was designed to break.

The decisions that the international community makes now will quite literally impact our world forever. Whistleblowers are the best – perhaps only option – to prevent catastrophe.

/>i

/>i